ABERDEEN – On a recent Wednesday morning, 10-wheelers brimming with spuds came and went in every direction, making the trip from fields to cellars and back again.

Amid the bustling energy, signs along the roadside announced: “Harvest Help Needed.”

To answer that call, rural Idaho districts have long held harvest breaks, putting school on pause for a few weeks each fall so students and teachers can pitch in at local farms.

Located in the heart of Bingham County – which produces most of Idaho’s potatoes – Aberdeen is one such community. Middle and high school students were out this week driving potato trucks, picking and stacking potatoes, and laying pipes.

“We rely on them pretty heavily,” said Kendell Foster, who manages Foster Farms.

Otherwise, Kendell said, finding help for just a few weeks during harvest is nearly impossible. Plus, it gives teens a chance to learn life lessons.

Foster Farms typically hires around 10 students every break, and a number of other farms in the area hire teens as well.

“It encourages kids to want to get an education and not do this the rest of their lives … because it is hard manual labor,” said Terri Foster, who co-owns the farm with her husband.

After days of conveyor belt work, kids go home with sore fingers and endless visions of potatoes filling their heads.

“By the end of potato harvest, kids are glad that it’s done – and they’re maybe even grateful to go back to school,” she said.

Terri said the community has considered discontinuing harvest break because of the safety hazards kids face, but she and her husband always push to keep it in place because of the insight it provides to local youngsters.

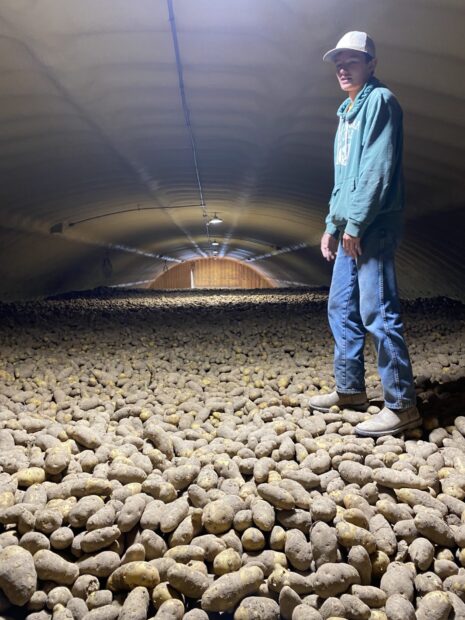

Her youngest son, Canon, is 15 and has been working on the family farm for years. This week, he and Logan Vaughn, 17, were laying down aeration pipes in a potato cellar.

Canon and Vaughn said they plan to save the money they make for college. Thinking about the paycheck they’ll earn helps them endure the long, 12-hour days spent outside and on their feet.

“You never know how hard it is until you go through it,” Vaughn said.

For Canon, who’s on the football team, the days are even longer. He works from about 7 or 8 a.m. until about 8:30 p.m., then has practice from 9 to 11 p.m.

He said that’s the life of a farmer – not getting much sleep until harvest is over.

“It’s hard to get out of bed sometimes, but you just have to push through it if you want to be successful,” Canon said.

Neither teen plans to go into farming. Canon is thinking of becoming a chiropractor or dentist, and Vaughn is interested in coding.

Nearby, 13-year-old Kooper Jolley was spending his first day on the job picking rocks, dirt clods, and bad potatoes off a conveyor belt as the spuds made their way into the cellar. So far, he was having fun.

“It’s a lot better than playing video games, and you get paid,” Jolley said. “You get to be outside, meet new people, work, and not sit around on the couch.”

Jane Ward, the superintendent of Aberdeen School District, said she works with farmers every year to determine when harvest break should be held. They meet the week before it’s planned to double check that the weather and temperatures are right for harvesting.

“Farmers can call and say they need to move it up or back, and we do what they ask,” she said. “This is a major (event) for students, farmers, and our community.”