When it comes to teacher salary in Idaho, location matters.

A teacher stands to make $35,000 more — or less — depending on the school.

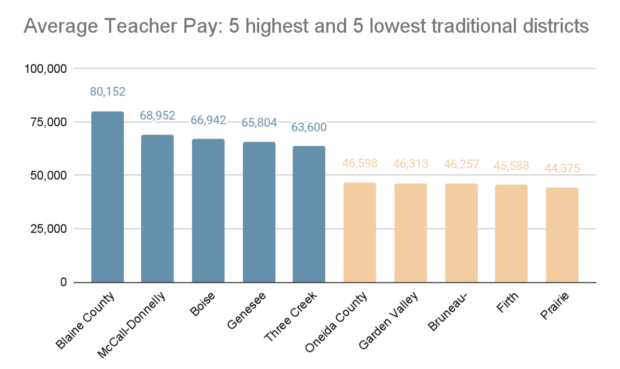

That figure — $35,777, to be exact — is the discrepancy in average teacher salary between Idaho’s highest and lowest-paying districts (Hailey’s Blaine County School District and Prairie Elementary).

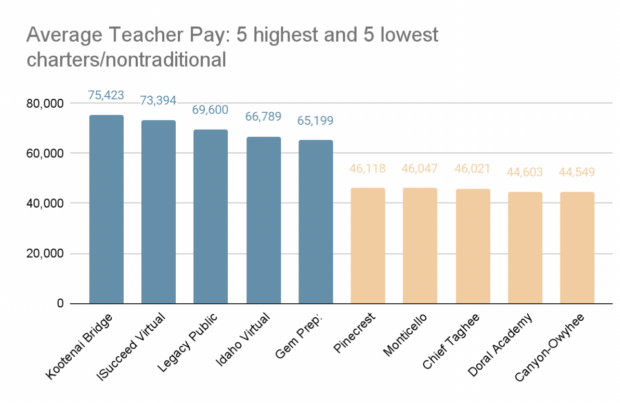

The charts below compare the state’s most and least lucrative average teacher salaries, as sorted by traditional public schools and nontraditional/charter public schools.

Data source: State Department of Education

Take a look at the average teacher salary in your district or school here.

Location-based pay gaps are nothing new in education. Understanding why the chasms exist requires a look at how teacher pay is funded.

The way the state divvies out money for teacher pay is complex. But basically, the state provides districts with a certain amount for teacher salaries that is dependent upon enrollment and teachers’ movement on the career ladder. That movement is based on education, experience, and evaluations. Even so, performance makes minimal impact on teacher pay; it seems that education, experience and location are the key determinants.

If that wasn’t complex enough, there’s a caveat — the formula is a bit different for charter schools. Charters can meet a lower enrollment threshold than traditional schools to earn funding.

The salary funds from the state don’t seem to be enough. As Lisa Arnold, the superintendent of the Lakeland School District told EdNews in August, “On average, the state only covers about 70-75% of salaries and benefits. Local patrons have to support the rest through levies, and it’s the same throughout the state.”

Whether or how districts make up the difference between what’s provided by the state and what’s needed to recruit and retain depends on the community and type of school.

Wealthier communities, like Hailey and McCall, have more means to supplement state education funding. More rural or economically disadvantaged communities are less likely to be able to turn to taxpayers to pad teacher salaries. And charter schools are unable to put levies on a ballot.

There have been legislative attempts to close those gaps. Recently, the state offered a grant opportunity to teachers working in rural and underserved districts. Those awarded the grant will receive $12,000 over four years to put toward educational expenses. It’s not the same as a pay increase because the funds have to be used in a certain way, but they do provide some financial relief.

And Gov. Brad Little recently touted a goal of funneling an additional $145 million into teacher pay and boosting Idaho into the top 10 in the nation for starting teacher pay. In 2020-21, Idaho ranked 29th nationally, according to the National Education Association.

If Little’s funding goal became a reality, it would increase average teacher pay across the state — but would do little to close the geographical gaps.

And there have been other efforts throughout the years to boost teacher pay — like master teacher premiums (now defunct) and an advanced professional endorsement program. Statewide, average teacher salary has grown by 18% since 2016-17. But when compared to teacher salaries in other states and after accounting for inflation, teacher pay is still relatively low — a reality that’s only exacerbated in Idaho’s lowest-paying schools.

Pay remains a top concern among Idaho educators.

In a fall 2022 EdNews survey of more than 500 Idaho teachers, 52% said low pay was a “serious” or “very serious” concern, and as of October, 27 of 36 administrators surveyed by EdNews said their teacher turnover this year was “more than average.”

Data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.