Heritage Community Charter School in Caldwell welcomed its first class of students in the fall of 2011. By June 2012, it was uncertain the public charter school would reopen after its first summer break.

Money was scarce. The school’s board was in a state of upheaval. Its unaccredited high school pilot program ended. Heritage received an academic rating of just two of five stars from the Idaho Department of Education. The Idaho Public Charter School Commission, which authorizes the school, warned it was considering sanctions.

“I’ll be honest: We struggled,” says Richard Hammond, parent and vice-chairman of Heritage’s board. “We really did.”

Fast forward to 2015. Heritage is financially solvent and quickly filling its halls with K-8 students. They leave proficient in both English and Spanish thanks to the school’s dual-language immersion program, a rarity in Idaho public schools. Its board, no longer warring, is looking to the future. There’s even a waiting list for grades K-5.

The credit for the school’s success goes to Javier Castaneda, Hammond says, who became principal in 2012.

“I could not dream of a better person to lead the school,” Hammond says. “He’s a good man. He cares. He works very hard.”

The jump to four stars

Heritage’s remarkable turnaround began with Castaneda’s hiring, says board Vice Chairman Robb MacDonald.

“We wanted someone who was going to be able to come in and take charge, fulfill that leadership position, and rally the rest of the school community behind him,” MacDonald says. “We interviewed Javier and we felt like he was a good fit. He was actually a lot better than we even knew at the time.”

Hammond credits Castaneda’s “rare” combination of business sense and people skills. “He has been instrumental in bringing the vision,” he says.

Castaneda came to Heritage from Oregon, where he worked in elementary education. His first order of business: Replace half of Heritage’s teaching staff. Some had quit because the school’s high school pilot ended, but some chose not to continue for a second year, Castaneda says.

“The big piece when I started, and when all of these new staff started, was to create a common vision and direction,” Castaneda says. “The board came together, the administration came together, the teachers came together, and it was really asking, ‘What is it that we want from our school for our students? It really boiled down to just one thing: No more percentages of looking at student success. We’ll focus on each, individual child.”

That doesn’t mean data is out of the picture — far from it. Instead, Castaneda says, the change comes from the way the data is used. Castaneda and Heritage teachers established professional learning communities who meet each week and evaluate students’ current results.

Each bit of data is analyzed by asking three questions, Castaneda says: What do we want our students to learn? How do we want them to learn it? What do we do if they didn’t learn it?

“If we don’t shift from percentage to child by child, you’re not going to get that growth,” Castaneda says. “The students aren’t going to learn. We’re not going to be sure that each child is learning.”

The process is reassuring to MacDonald, who has two daughters enrolled at Heritage.

“In organizations where you’re dealing with a lot of people, it’s easy to get into the mindset of dealing with numbers,” he says. “But the fact that the school is focusing more on looking each individual and finding out what the needs are and figuring out what we can do to help — it’s encouraging. I know if my kid’s ever on the low end, or the high end, or anywhere, they’re being looked at specifically for what their needs are. It makes me feel a lot better.”

Castaneda says Heritage’s teachers make the school’s academic approach work.

“Our teachers are amazing,” he says. “As we’re looking at this child-by-child concept, they’re volunteering their time after school to stay after with select groups of students who may be struggling to provide them with an extended learning opportunity.”

So far, the work is paying off. Heritage received just two stars from the Idaho Department of Education during the 2011-2012 school year. By 2012-2013, the school had jumped to four stars.

“The teachers were extremely thrilled, I was thrilled and the board was thrilled to see that we really could come together to make this school move forward,” Castaneda says.

Core Knowledge meets dual immersion

Heritage, like White Pine Charter School in Ammon, is a Core Knowledge school. The emphasis is on a broad, content-rich education in history, science, literature, the arts and geography.

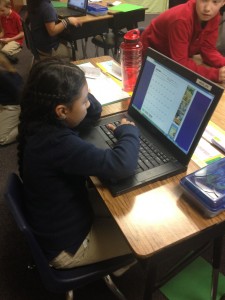

What sets Heritage apart is that classes are taught in Spanish and English, adding an extra level of rigor to an already demanding curriculum.

“As our students are going through, we’re teaching them through that vehicle of classical education,” Castaneda says. “And we’re doing it with a dual-immersion model. It’s quite a lot to bite off for anyone starting here at the school.”

Shantell Mullanix, who is in charge of federal programs and counseling at Heritage, has a son in first grade at Heritage and a son who is taking Spanish in high school. Her sons speak Spanish at home, she says.

“What I’ve learned is that high school Spanish is kind of the textbook Spanish, whereas (Heritage students) are immersed in the language,” Mullanix says. “It’s the dialect they’re hearing all the time. It’s been really interesting.”

The dual language program is “critical” to the success of the school, Castaneda says.

“It’s really a big piece,” he says. “Research shows that students who are multilingual, over time, will have greater gains academically than their monolingual counterparts.

Maci Mattravers, a fourth grade student at Heritage, didn’t know a word of Spanish when she started first grade at Heritage. After a few days of instruction in English, her teacher changed gears.

“All of a sudden, she said, ‘OK! Put your thinking caps on. We’re going to Spanish now,’ ” Mattravers says. “It was really exciting.”

Most of the school’s teachers are either new to a dual-immersion program or have limited experience. Castaneda says Heritage is investing in professional development, including national dual-language conferences. But the program faces a larger hurdle, as well — the school is 55 percent white, 40 percent Hispanic and 5 percent other. The school also has a free-and-reduced price lunch percentage of 71 percent.

“The challenge we face is having a sufficient number of native Spanish speakers in the community to fill part of the need of a dual-immersion program,” Castaneda says. “It’s simply because of where we’re located. Over time, dual-immersion programs that have succeeded have had an equal number of students who speak native English and who speak native Spanish.”

Growing for the future

Hammond says joining the school’s board was a wake-up call. “There’s a lot about the school system, and the way the state handles the funding, that I didn’t understand at all,” he says.

Like all public charter schools in Idaho, Heritage does not receive additional funding from public levies or bonds. Board members say a large part of Heritage’s turnaround involved rethinking the school’s funding and putting the focus on priorities. MacDonald renegotiated the school’s five-year building lease, which was a crucial step toward solvency.

“Finances — that’s a problem statewide,” MacDonald says. “Schools have trouble with finances because the education system may be underfunded. The charter school system is underfunded. That’s a battle we’re constantly working with and I feel like we have control of it and we’re moving in the right direction, but it’s just always there.”

Castaneda has tightened budgets among his staff, and Mullanix says teachers have been resourceful.

“The teachers have been amazing about going and asking for donations, writing grants, seeking whatever they can find for the classroom,” she says. “I’m just very proud of them for always taking those opportunities.”

Finances will be an ongoing struggle, MacDonald says.

“We have such a great program here,” he says. “It’s a shame to have the program suffer because we’re a little short on funding. Everything else is working so well, so we’re trying to bridge that gap in funding. We really appreciate what the teachers do to seek it.”

Funding will become more of an issue as the school grows. Castaneda says the school hasn’t quite met its enrollment cap of 540 students, but expects to. In the meantime, he’s been thrilled with the support the school has received from the community — free school supplies, support for fundraisers, and donated time and money.

Heritage is gaining control of its finances, but charter school funding is a statewide issue, Hammond says.

“It costs the same for a chair, whether the kid is sitting in a chair here or they’re sitting in a chair in a public school,” he says. “The chair is the same price. Why do we treat a child differently because they’re in this place?”

This is the fourth in a six-part series featuring Idaho charter schools. The first was about Boise’s Anser Charter. The second was about White Pine. Another was about Syringa Mountain in Hailey. This series is being provided by the Idaho New School Trust, which is funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation.

Disclaimer: IdahoEdNews.org is funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation.