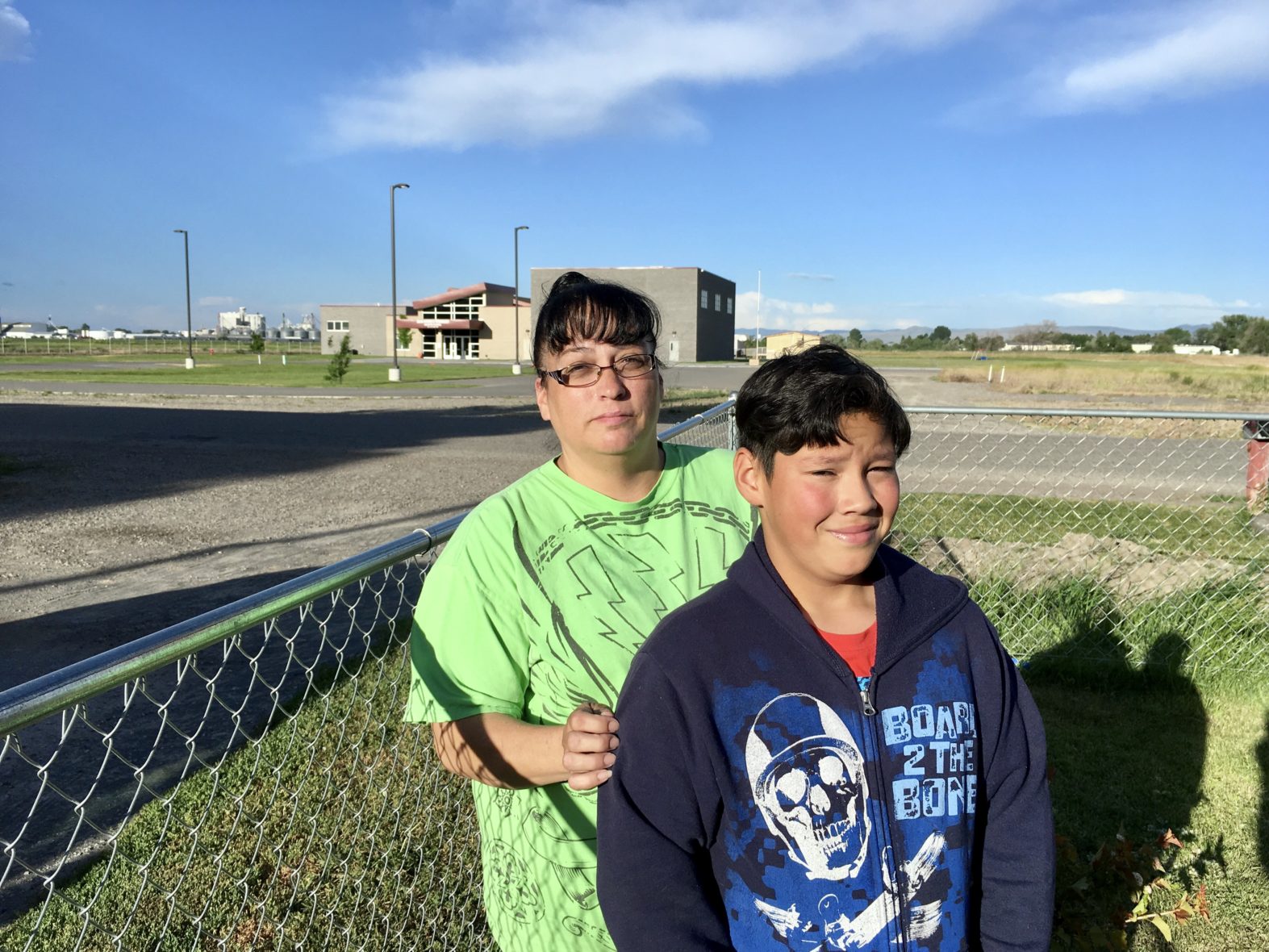

Helena Arreguin lives in a small blue house across the street from the public Idaho Science and Technology Charter School, but says she never knew her three children could enroll there for free.

“I just always had the impression it was for smarter kids,” said Arreguin, 46, referring to the Blackfoot-based school’s emphasis on science and technology. “My kids are all on IEPs (individual education plans), so they go to the Snake River School District.”

Arreguin’s three children are Hispanic, a demographic largely poorer than others in Idaho and one markedly underrepresented in Idaho’s public charter schools, which have been popping up across the state for nearly two decades now.

In February 2016, a report presented to the State Board of Education revealed for the second straight year that Idaho’s charter schools governed by the Public Charter School Commission are far less diverse than the state’s traditional public schools.

The state’s top school-choice leaders say they acknowledge these disparities, and are working on the issue. But many PCSC charter schools, which often gain praise for their academic performance, still don’t offer programs for poorer students, including free-and-reduced lunch and transportation services. In addition, many Idaho Hispanics report not knowing much — if anything — about local charter schools, or feel reluctant leaving their regular neighborhood schools in order to attend them.

The disparities

The 2016 report outlines a number of disparities between Idaho’s charter schools and regular school districts:

- Eighty-nine percent serve a lower percentage of special-needs students than their surrounding districts.

- Ethnic minority students are underrepresented in 94 percent of charter schools; in 79 percent of these schools, the difference exceeds 3 percentage points.

- Eighty-three percent enroll no students with limited English proficiency (LEP) skills — making it the most underrepresented group in charter schools.

- In 66 percent of charter schools, the percentage of students who qualify for free-and-reduced lunch is at least 3 percentage points lower than in surrounding districts.

Meanwhile, data provided by the State Department of Education reveal that at least 12 brick-and-mortar PCSC charter schools don’t participate in the federal free-and-reduced lunch program. By comparison, just five regular public schools out of the state’s 115 school districts don’t participate.

And at least five brick-and-mortar PCSC charter schools in the 2016 report don’t offer bus services for kids.

PCSC brick-and-morter schools that don’t offer free-and-reduced lunch

Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy

Alturas International Academy

Connor Academy

Monticello Montessori

North Idaho STEM Charter

Sage International School

Bingham Academy Charter

Idaho Science and Technology Charter School

Kootenai Bridge Academy

Richard McKenna Charter

Syringa Mountain Charter

The Village Charter School

The debate

School-choice opponents argue that the absence of these services enables charter schools to discriminate by enrolling a more selective, higher-performing student demographic, with parents who are more likely to pay full price for a school lunch or drive their kids to school.

PCSC brick-and-morter schools that don’t offer busing services

Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy

North Idaho STEM Charter

Rolling Hills Public Charter

Syringa Mountain Charter

The Village Charter School

“It’s clear discrimination, and I don’t know how these schools get away with it,” said Madison School District superintendent Geoff Thomas, a longtime, unabashed critic of charter schools. “They simply cater to upper-class white children.”

Though Idaho’s public schools can opt out of the federally funded free-and-reduced lunch program and busing services, state law requires them to provide equal opportunity to all students, regardless of ethnicity or special needs. The lack of these services contributed to a 2015 complaint filed with the Office of Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Education by the Idaho-based Centro de Comunidad y Justicia (Center for Justice and Community).

The complaint called for changes to Idaho’s charter school admissions process, which gives enrollment preferences to employees’ family members and the siblings of current enrollees. It also called for added busing services and outreach requirements to typically underserved areas.

Center for Justice and Community director Sam Byrd said the Office of Civil Rights ultimately requested more evidence to support the group’s complaint. Though the CJC began compiling lists of schools that weren’t providing services to poorer students, Byrd said, a lack of resources and a “general lack of concern from the public” ultimately ended pursuing the complaint.

“We are a small nonprofit and felt that other Latino organizations here didn’t support us, and that many people are simply OK with this (inequity),” Byrd said. “Our efforts to bring equity to Latinos in Idaho’s public schools has been a horrible failure here.”

But demographic disparities aren’t as blatant when charter schools are compared with some of Idaho’s largest school districts, said Terry Ryan, CEO of Bluum, a Boise nonprofit that supports school innovation, including charter schools. Ryan pointed to SDE statistics comparing charter school demographics with West Ada and Boise district schools.

“While charters aren’t as diverse as state averages, they are more diverse than the West Ada School district on average and are darn close to Boise district averages,” Ryan said.

Still, the percentage of low-income students attending Idaho’s charter schools rests at 35 percent, compared to the rest of the state’s 46 percent. And while Hispanics constitute 18 percent of Idaho’s total enrollment, charters reported enrolling just 10 percent in 2015-16.

Ryan added that several charter schools are working hard to buck these demographic trends. Chief Tahgee Charter School, on Eastern Idaho’s Fort Hall Indian Reservation, is a non-PCSC charter that provided free or reduced-price lunches to all of its students in 2016-17. Alturas International Academy, a PCSC charter school in Idaho Falls, will relocate to a lower-income and more “walkable” part of the city in 2017-18.

But while some school-choice advocates and educators reinforce the necessity of attracting and enrolling a more diverse group of kids, others say greater obligations on the part of families hoping to attend charter schools simply come with the territory.

“People often have to provide transportation for their kids if they enroll in another regular public school — not just a charter,” said Dan Nicklay, principal of the Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy, a high-performing college prep school in North Idaho that has garnered national acclaim from the Washington Post, U.S. News and World Report and Newsweek Magazine. “I just don’t like the idea of thinking that if charters don’t work for everybody, they shouldn’t work for anybody.”

Nicklay pointed to laws prohibiting charter schools from taxing local patrons via supplemental levies and school bond issues. The vast majority of Idaho’s regular public schools tap into property taxes to help offset busing and food expenditures. He also questioned the process of gathering data for the 2016 PCSC report that revealed the demographic disparities between regular schools and charter schools — including deep disparities in his own school, which enrolled no special education students in 2015-16.

“We had to send out surveys to gather that data and had only a 20 percent response rate,” said Nicklay, who claimed that fewer families in his school were apt to provide details of their income, since Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy doesn’t provide free and reduced lunch. “I can’t provide any numbers, but I’d say we serve a student body similar to that in other schools in our area.”

The 2016 PCSC report revealed that fewer than 2 percent of Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy’s families qualified for free-and-reduced lunch. Coeur d’Alene School District students reported 40 percent.

Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy provides neither free-and-reduced lunch nor busing for its roughly 700 students — and Nicklay said he has no plans to establish either anytime soon.

The lack of understanding

Madison’s Thomas called claims of equal diversity in Idaho’s charter schools “bull pucky.”

“I think it’s pretty clear at this point,” he said. “Many of these schools just don’t want to serve certain types of kids.”

Still, a variety of Idahoans report a lack of knowledge regarding the opportunities offered to students through public charter schools.

“We have to go to the Blackfoot School District because we live in that district,” said Patricia Botello, a Hispanic mother of three who lives a mile from ISTCS in Blackfoot. Botello is one of at least four other limited-English Hispanic mothers living in a trailer park located roughly a mile from the charter school who say they don’t know what a charter school is.

They aren’t alone. In the 2017 “People’s Perspective,” a public opinion poll conducted by Idaho Education News, just 34 percent of the 1,004 Idahoans surveyed said they knew a “great deal” or “quite a bit” about Idaho’s charter schools.

“I’m not going to act like all of this isn’t something we need to be looking at very closely,” Ryan said. “Charters can and should do more, and we are working in our capacity as a funder to make this happen.”

Disclosure: The People’s Perspective survey and Idaho Education News are funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.