GOODING — Administrator Brian Darcy, principal Gretchen Spooner and student Ella Kidd are not related, but all consider their school to be their home.

The Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind is more than just a place to learn for this trio, it’s where they live and interact with people of a similar culture.

They traveled different paths to the Gooding campus, but each eventually settled at the place that has become one of Idaho’s most valued educational offerings.

The Idaho School for the Deaf and the Blind has transformed its 100-year-old self over the past decade. After surviving a near shutdown by Idaho government to be turned into a women’s prison, today it brags of producing its largest high school graduating class ever.

“We’re doing some incredible things here and I couldn’t be more proud to be a part of it,” said Darcy, the school’s top administrator, who moved his family from plush urban accommodations to on-campus housing seven years ago.

Darcy leads not only the school but also the Idaho Education Services for the Deaf and Blind, established by the Legislature in 2009. The IESDB provides statewide services for students who are deaf or hard of hearing and/or blind or visually impaired. The IESDB assists school districts and state agencies in providing accessibility, quality and equity to students with sensory impairments through a continuum of services and placement options, including residential education in Gooding.

The IESDB has 35 outreach employees who serve about 2,000 children and their families throughout the state.

Another 22 teachers work on the Gooding campus, aided by classroom assistants, cottage staff and nurses who serve 94 residential students.

Overall attendance has doubled in the past seven years with a record graduating class of 20, including four who are college-bound.

“This is like a home to me,” said Lisa Newton, a teacher on the Gooding campus who traded in a career as an architect to return to her alma mater. She is deaf and graduated from the University of Idaho. “This is a better fit and I can be a mentor.”

A residential campus

The Gooding school and home base for IESDB sit on 40 acres donated in 1906 by Sen. Frank R. Gooding, who mandated it be used for education purposes. The campus includes school facilities, cottages, sports fields and a home for the administrator. Darcy lives there now, plus he grew up there when his father, Ronald Darcy, served as the administrator. He attended nearby Gooding High, part of the Gooding School District. His sister, who is blind, graduated from the ISDB.

Darcy encourages most kids from around the state to attend school on the Gooding campus, even though it means leaving their families during the week. In a neighborhood school, a blind or deaf student is likely only able to communicate through an interpreter with staff, students and family. At ISDB, students can submerge themselves in American Sign Language and Braille where most everyone, teachers and students, communicate in both languages.

“We know there are a lot more kids who could do well on campus,” Darcy said. “It’s a placement, not a sentence.”

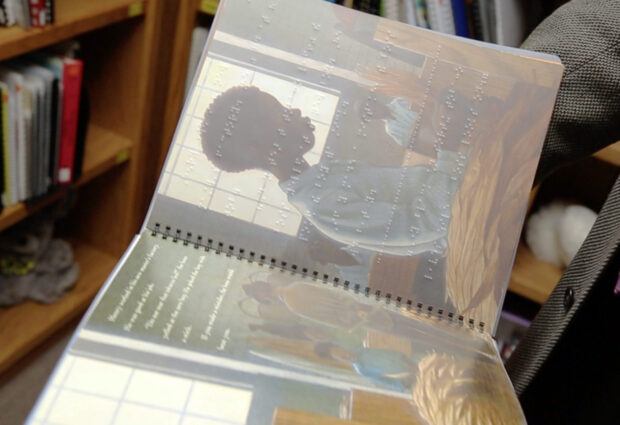

Blind students learn to read and write in Braille and math is taught in a form of Braille. Printed books are translated to Braille on campus. Technology is used as a tool to take classes online, including dual credits through the College of Southern Idaho.

“Everything we do is tied to language,” Darcy said.

Those who choose the residential school also learn life skills necessary to be independent, including cooking, housekeeping and planning.

“Our staff is extremely specialized,” Darcy said. “The reality is a district couldn’t touch what we can offer.”

Each cottage holds about 10 students and they eat family style, do chores and keep their rooms clean. They have study groups, TVs and lounging areas. They are allowed to have friends and dates over, but only with adult supervision.

The kids arrive on Sunday nights and returned to their homes on Thursday evenings, traveling by bus and some by plane to North Idaho.

Principal Gretchen Spooner

Gretchen Spooner and her family have long relied on IESDB .

Gretchen knew nothing about deaf education when her young daughter lost her hearing from an illness. She tried to teach herself sign language from a library book but she couldn’t effectively communicate with her daughter. The outreach services from IESDB “saved us” she said and was instrumental in convincing the Spooners to move their family of five from Driggs to Twin Falls so their daughter could receive the specialized education.

Gretchen, a trained anthropologist, went on to earn a master’s degree in deaf education. She now serves as the ISDB principal. Her daughter, who inherited Gretchen’s zest for learning, earned a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in English and teaches at Rochester Institute of Technology in New York.

“These services were so powerful for my family,” she said. “Deaf people have their own culture and residential schools support that culture.”

Student Ella Kidd

The school’s culture saved Ella Kidd. She graduated last month from ISDB as senior class president with a 3.6 grade-point average after a history of mediocre performances in a traditional school environment.

She had no friends at her Nampa school where she was the only deaf kid and she taught herself what little sign language she knew. She felt isolated and lonely.

After just one day at ISDB, her mother noticed a difference. She began to excel academically and become a part of the community.

She learned sign language quickly, which opened up communication with friends and learning in the classroom.

“I became a happy, smiling and confident person,” said Ella, who wants to study biological sciences and become a zookeeper.

“Friendship is about playing together or chatting and that’s so important in peer relationships,” Spooner said. “She can do that here.”

Statewide services

The IESDB supports three pre-schools in Meridian, Gooding and Pocatello and another will open this year in Coeur d’Alene.

The statewide staff provides early learning intervention, family consultation, counseling and qualified interpreters for children from birth to age 21.

On campus is a facility that translates thousands of books into Braille, often using trained prison inmates to help. The technical education program offers welding and woodshop courses.

The campus is active year-round, supporting summer camps for the deaf and hearing impaired. Students learn skills that will apply to joining the workforce. They teach kids how to interview and be reliable on the job. Staff then helps students find minimum-wage summer jobs at coffee shops or grocery stores.

“The entire school can communicate with kids,” said Darcy, whose background is in deaf education, psychology and mental health treatment. “It’s the least restrictive environment for learning and communicating.”