Danfer Reyes will be a first-generation high school graduate.

The Wood River High School senior wants to be chef or a restaurateur, and plans to go to college to study culinary arts. But since he can’t afford college, he’s joining the Idaho National Guard, hoping part-time military service will help him cover college costs.

It’s a tradeoff. Time also works against Danfer, and any other student who puts off college: The longer the wait, the higher the cost.

Idaho’s political and education leaders want students such as Danfer to continue their education after high school. Ultimately, state leaders want 60 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds to hold some kind of college degree or professional certificate.

University leaders put the best face on the affordability issue. But they also know they are losing some students — ones who never show up, and ones who drop out along the way.

“We’re asking 18-year-olds to make sophisticated financial decisions, and that’s tough,” University of Idaho President Chuck Staben said.

College math, 101 …

“I think the media loves to talk about sticker price,” Boise State University President Bob Kustra said.

And Idaho’s college sticker price remains one of the lowest in the nation. On average, only five states charge a lower in-state tuition.

However, not all the numbers are as encouraging.

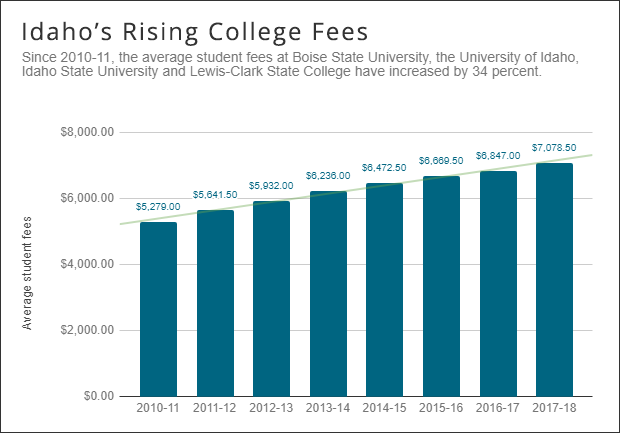

This fall, the average fees at Idaho’s four-year colleges and universities came to $7,078 — up 34 percent since 2010-11. During that same time period, the rate of inflation was 13 percent, according to the federal Consumer Price Index.

Over the past four decades, governors and legislators have engineered a conscious and continuing cost shift. They now expect students and their parents to pick up a greater share of the cost of college.

Over the past four decades, governors and legislators have engineered a conscious and continuing cost shift. They now expect students and their parents to pick up a greater share of the cost of college.

Two snapshots put this shift into sharp focus.

In 1977-78, Idaho colleges and universities received $54.2 million in tax dollars from the state’s general fund, while student fees made up a $3.8 million sliver of the budget.

In 2017-18, that gap has shrunk almost entirely. Colleges and universities will receive $287 million in state tax dollars, and $262 million in student fees.

Over 40 years, the general fund budget for higher ed has increased fivefold — while the amount of money collected in fees has increased by a factor of 69.

… and college history, 101

The $287 million higher education budget accounts for 8.3 percent of this year’s state budget. A quarter century ago, higher education received 13.8 percent of the state budget, a share that hasn’t been matched since.

To be sure, state budget-writers have faced other fiscal pressures over the past 25 years — the rising cost of Medicaid, for example, and the pressure to reverse unprecedented K-12 spending cuts. But the cost shift carries consequences, and for years, Idaho’s politicians have been warned of them.

Two warnings came in 2012, in the wake of the recession.

For a report titled “Reducing Barriers to Higher Education,” the state’s Office of Performance Evaluations interviewed students, counselors and staffers working on TRIO, a federal program designed to help at-risk students make the jump to college. State auditors heard the same message over and over.

“The ability to pay for college is by far the greatest barrier to overcome when making decisions about pursuing postsecondary education. Whether it is access to financial aid and scholarships or insufficient grant amounts, paying for postsecondary education weighs heavily on the minds of both counselors and students.”

Later that year, the State Board of Education launched Complete College Idaho, which has grown into a multiyear and multimillion dollar effort to help students succeed on campus. The State Board’s Complete College Idaho Plan included some sobering statistics about college affordability: Young people from wealthy families finish college at a 60 percent rate, while young people from poorer families graduate at only a 7 percent rate.

“This disparity does not exist because young people from higher-income families are smarter or more talented — they are simply afforded more opportunities.”

Affordability options

In 2017, Gov. Butch Otter’s higher education task force spent considerable time talking about affordability. The group recommended putting money into an “adult completer” scholarship for older students who are short of a degree.

Another recommendation: Make the Idaho Opportunity Scholarship available to students with high school GPAs or 2.5 or higher. The current cutoff is a 3.0 GPA, and as it is, thousands of eligible students still don’t get a share of the limited money available.

The idea of tuition-free community college — an idea that is picking up momentum in cities and states across the country — received only a passing mention. And no committee support.

For a state that doesn’t even fully fund its Opportunity Scholarship, tuition-free community college is a “mega-leap,” said State Board President Linda Clark, a task force co-chair.

“Frankly, we have some preliminary hills to climb before we can even get to that conversation,” she said.

As state Rep. Ilana Rubel points out, free college isn’t means-tested, so it’s available to students regardless of ability to pay. But after serving on the task force, Rubel isn’t sure the group did enough to address rising costs and scholarship scarcity.

“I think we’re really underinvesting in the affordability side of things,” said Rubel, D-Boise.

‘We’re OK, so far’

Blaine County is one of Idaho’s wealthiest school districts, home to pricey vacation properties and a year-round tourist trade. Blaine County’s 2017-18 property value exceeds $9.4 billion and ranks third in the state; the district’s 2016-17 enrollment ranked No. 24. Thirty-eight percent of Blaine County students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, well below the statewide rate of 49 percent.

Yet even in Blaine County, the realities of college costs can hit hard.

Wood River High School senior Angel Magana doesn’t plan to follow her older sisters to the U of I. She said the prospect of racking up four years of student loan debt was “overwhelming.” She plans to go to cosmetology school after high school, then enroll at the College of Southern Idaho to study business and finance. She hopes to leave CSI with an associate’s degree — and then open her own salon.

“I want to be able to have one decent job that I own,” she said.

Itzel Chavez wants to become a surgical technician, and hopes to attend Salt Lake Community College in Utah next fall. She knows it would be less expensive to attend college in Idaho. But she has sisters in Utah, she loves SLCC’s campus and believes she will get more hands-on instruction there.

Itzel is applying in-state as a backup plan, and she’s working to put money toward SLCC. “We’re OK, so far. We have a plan for it.”

That plan involves the Western University Exchange, a multistate cooperative that allows some students to attend out-of-state programs at a reduced price. Itzel would still have to pay 50 percent more than an in-state resident attending SLCC. But without WUE, she’d pay three times as much.

Liz Clark helped Itzel find out about WUE. The Blaine County career and college transition coordinator spends a lot of her time helping families sort through the weighty issue of paying for college.

Even in Blaine County, very few families can simply afford to send their children anywhere, with no thought of cost. But many of Clark’s college-bound students have a fearless streak. They’re willing to look for an answer — even if it means scraping up scholarships or signing off on loans.

“You’re young and dumb, in a good way,” she said.

The debt dilemma

Not all high school seniors are so bold and brazen.

Kustra saw that firsthand in April.

At the invitation of a teacher, Kustra spoke to a skeptical audience of 13 seniors at Owyhee County’s Marsing High School. They had the grades for college, but not the inclination.

Some of the students were “freaked out” at the prospect of going into debt, Kustra said. The students reflected their parents, who operate family farms or ranches on a pay-as-you-go basis, and instilled that thinking into their kids.

It’s a variation on a familiar refrain.

Idaho education leaders have long acknowledged that it’s tough to convince rural graduates to go to college — and it’s especially difficult to attract first-generation students from small-town Idaho. For years, many rural high school graduates have believed they could get a good job without going to college, and many times, they were right.

For students like Kustra’s class full of students in Marsing, college debt is viewed as an unnecessary luxury.

Yet thousands of Idaho students willingly incur debt: all told, Idahoans’ collective student loan debt totaled $5.7 billion, according to a U.S. Department of Education report issued in September.

But there can be a difference between bad debt and good debt. Bad debt comes when a student takes out $15,000 or so in loans and gets scared off — and drops out of college with debt and no degree. Good debt can mean graduating with $25,000 in outstanding loans, but a degree that commands a $50,000 starting salary.

So while two-thirds of U of I graduates leave school with debts, Staben tries to urge students to ride out the process.

“That debt is really a great investment in your future,” he said. “Nonetheless, I think it’s a huge psychological barrier.”

About this series

In “Life After High School: Options And Outcomes for Idaho Graduates,” Idaho Education News takes an in-depth look at the state’s “60 percent goal.” Why is Idaho still struggling to convince high school graduates to continue their education? We look at the policies that shape this issue — and talk to students about their plans and the personal decisions.

Here’s the series at a glance:

Day One. After five years and $100 million, Idaho remains far from its ’60 percent goal’

Day Two. A defining decision: Five high school students talk about their plans

Day Three. As Idaho tries to sell the value of college, the sticker price keeps rising

Day Four. It will take even more time and money to reach Idaho’s ’60 percent goal’