The unincorporated community of Ola is a one-street loop that bumps off of Sweet Ola Highway, 30 miles north of Emmett. You could miss the place just by glancing down to change the volume of the radio.

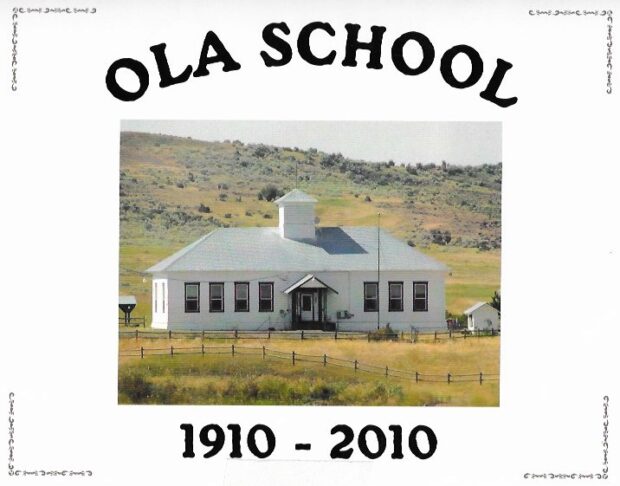

Ola has two stop signs, one where town starts, and one where it ends. It has a shuttered cafe and a market where the “C” was shaved off a Cola sign that now reads “Ola General Store.” And it has what preservationists call Idaho’s “oldest two-room schoolhouse” — a building that’s to be renovated thanks to the work of a local community group that raised funds to save the building.

The Ola School, a white building overlooking the community, is empty of children because of problems with the foundation, lead paint and dry rot. The 18 Ola elementary students have been attending school in the town’s community hall since 2019.

But this year, Emmett trustees voted unanimously to begin renovations at Ola School.

Students and staff members are hopeful they can move back into the old building in the fall. “It’s an amazing feeling, that we’re going to be back,” said Ola teacher Amy Davis.

The construction is estimated to cost $718,000. A local group called the Save Ola School Committee has raised about $355,000, including grant money, to help with costs.

On March 30, the board approved the district’s request to use $400,000 of ESSER 2 funds to complete Phase 2 of the renovation.

History of Ola School

Ola School was built in 1910 by Round Valley natives John Cantrell and William Bowman. The first teacher in the building was Roy Moss, who taught all eight grades.

While the Ola School building is 111 years old now, it’s not the first school in Ola. Previously, there was a school hidden behind the church on the south end of Ola. When that building closed, students were taught in the community hall, which at the time was less than half the size.

Today the section of the community hall that used to be the classroom is a kitchen that is used by the Ola Ladies’ Club – there is still part of an old black board hiding in the corner of the room. The students are currently learning in a new part of the hall, which was built in the 1970s and has served as dance hall, boxing training center for Harry “Kid” Matthews and a roller derby where Davis used to exercise.

Davis, who was taught in Ola School by her mother, said her favorite thing about Ola School is how involved the school is with the students and the parents. Because of how small the numbers are, Davis said it’s very important that everyone learns to get along and work together.

“The school really teaches community,” she said.

Gloria Sutton, Davis’ aide and former teacher, praised Davis’ connection between teaching community values and advancing the school using technology and other means.

Davis led the school in an environmental study program, which saw Idaho Fish and Game provide over 500 indigenous shrubs, trees and flowers for the students to plant around the school. A parent installed a drip irrigation system for the new vegetation.

Sutton also recalled how Ola School once had two students who were hearing impaired. Davis learned to be an interpreter for hearing-impaired students and taught the other teachers and students American Sign Language.

“We did every subject in sign language. We did spelling, everything, in sign language,” Sutton said. “Everybody. Every student learned it.”

‘We might lose our kids’

When the Emmett school district announced Ola School’s closure in the summer of 2019, community members showed up with their trucks and trailers to pack up everything in the building and move it down to the community hall.

Davis was upset about having to leave the school behind, but relieved they had a new home just down the hill.

“I was just glad we had a place to go,” Davis said. “Otherwise we would have closed and been shipped out. And we wouldn’t have had our community. That would have been heartbreaking.”

Without the community hall, Davis said the students would have been moved to another school, like Sweet-Montour. When Sutton started teaching in Gem County in 1969, some of the students were taken to Montour. It took a toll on them.

“They weren’t very happy,” Sutton said as she wiped tears off her cheeks. “People down there weren’t happy. I’ve never felt so sorry for children in my life. And so it was a flashback for me that we might lose our kids and I couldn’t just stand to see that happen.“

“If a community loses their school, they lose their identity”

Shannon Miller, the Save Ola School organizer leading the charge to save the historic school, is an Ola “transplant” who has taught a wide range of grades throughout the Treasure Valley for 33 years and moved to the area after retiring.

“I’m a glutton for punishment,” Miller shrugged when asked why she wanted to take charge of the project.

Miller was born and raised in Nebraska to parents who were both one-room school teachers.

“The first time I went to school I went to school in a one-room school,” Miller said. “And we lived in the basement. I have kind of a heritage of teachers in my family.”

And coming to Ola, Miller said she fell in love with the community very quickly.

“It’s like turning back the clock thirty-four years,” Miller said. “The work ethic. The desire to give the best they can to the kids’ education. They’ve done all the work in this community and this building.”

The school is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, another reason why Miller wanted to get involved.

“I have a real heart for old buildings.” Miller said. “We keep this building alive and we keep this community alive. If a community loses their school, they lose their identity. And I’ve seen it happen over and over again.”

Photos taken on March 18, 2021 by Nik Streng/Idaho EdNews.