The Idaho Education Network’s legal and financial crises didn’t start on Jan. 30, 2014.

But for many Idahoans, that’s when the fiasco came to light.

That’s when Administration Department director Teresa Luna requested $14.4 million to keep the high school broadband system online. The request shocked legislative budget-writers. Lawmakers agreed to an $11.4 million bailout, but the network’s future may be even cloudier than it was a year ago.

The problems won’t sneak up on lawmakers this year. And on Thursday, when Luna again appears before the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee, the headlines and the questions from the past year will provide the backdrop for the debate.

It’s all complicated. Here we go.

What will this cost taxpayers? The bottom line could turn out to be $8.9 million.

When lawmakers left town last spring, they funded the network through February 2015. They wanted to give themselves a chance to review the status of the project — and the need for more money.

But since then, the state has gotten plenty of bad news about both the contract and funding (more on both later). That means the bill has come due. Gov. Butch Otter wants $1.6 million to keep the network online through June 30, the end of the current budget year. He says it will take another $7.3 million to keep the project afloat for 2015-16 — $580,000 in ongoing operational spending, and $6.7 million in one-time money to hold things together.

It’s the second year of bailing out this system. Are lawmakers getting antsy? To an extent. Lawmakers from both parties have criticized the state’s handling of the dispute. One of the loudest critics, Rep. Judy Boyle, R-Midvale, calls the fiasco a case of “crony capitalism.” Some lawmakers have urged the Otter administration to dump a flawed contract and start over. “We’ve kind of been futzing around,” House Minority Leader John Rusche told reporters in January.

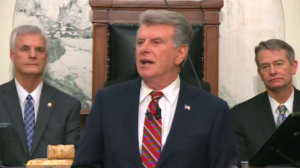

That said, there doesn’t seem to be much sentiment around the Legislature for yanking broadband from Idaho high schools. House Education Committee Chairman Reed DeMordaunt states what seems to be the prevailing sentiment: the network has too much potential to toss aside. “Have we hit a bump in the road?” he said in a news conference last week. “No question about it.”

If 2014 is any indication, lawmakers will probably fund the network — but not without some more grumbling.

But wait: Is there even a contract for the network? Not really.

The $60 million contract — engineered by Mike Gwartney, Otter’s longtime confidante and Luna’s predecessor at Administration — has been embroiled in the courts since 2009. Syringa Networks, a bidder for the contract, claimed it was unfairly cut out of the work. In November, District Judge Patrick Owen sided with Syringa and tossed out the contract.

That decision doesn’t bring the legal wrangling to an end. The state’s private attorneys and contractors have asked Owen to reconsider or explain his ruling. Syringa’s lawyers have urged the state to go back to its contractors — CenturyLink and Education Networks of America — and recover some $13.3 million that have been paid out under the disputed contract.

So, the state is looking for a contractor, right? Yes. And it’s moving quickly.

On Tuesday, the state opened up a bidding process for a short-term contract, to run things through 2015-16.

The state is hoping the “bridge contractor” will be able to secure project funding from Uncle Sam.

But isn’t the state looking for a long-term contractor? Well, yes.

That’s going on at the same time. But that’s much more of a long-term process. Would-be bidders can respond to the state’s “request for information” — telling the state what they think a contract should look like. That paperwork is due Feb. 15. This contract won’t go out to bid until summer, and probably wouldn’t be awarded until July 2016.

Curiously enough, Syringa CEO Greg Lowe likes the way the state is reaching out for information from bidders, and he says his company will respond.

In his Jan. 12 State of the State address — and in an extended interview three days later — Otter conceded the original deal was botched. “I’d like to see the contracts be correct and be good,” he said on Jan. 15.

Legislators may insist on that. For many lawmakers, the broadband fiasco is an illustration of a contracting policy in need of reform.

What’s the story with “e-Rate” funding? The network’s funding problems really began in early 2013. That’s when a federal contractor, the Universal Service Administrative Company, put the network’s e-Rate funding on hold — citing the ongoing dispute over the contract.

Lawmakers had no clue of the funding problem until January 2014, when Luna dropped the news during her JFAC presentation.

The funding problem is by now well-known, but still unresolved. The e-Rate dollars, collected from cell phone and landline bills, had once covered about three-fourths of the network’s operating costs.

But these dollars are still on hold. That’s why Otter put $8.9 million in the network’s budget requests. It’s also why the state is putting a rush on a new bridge contract, hoping it could qualify for the federal match.

Do districts have any recourse? They can apply for e-Rate dollars. And the state is encouraging districts to do just that — even though they face the same tight deadlines the state is facing with its bridge contract.

The state’s three largest districts — West Ada, Boise and Nampa — are looking at filling out their own paperwork. In West Ada’s case, it’s simply a matter of piggybacking on an existing application for $500,000 of e-Rate dollars to supplement other tech projects.

West Ada’s high school broadband application is a backup plan, spokesman Eric Exline said, in case the state doesn’t keep the network going. It would cost West Ada about $100,000 a year to equip its high schools with broadband. The videoconferencing equipment, used to broadcast courses from school to school, run about $20,000 per classroom.

Is the network really reshaping the high school experience? It depends which school you visit.

West Ada uses the equipment extensively to share classes in-house, among its high schools. Weiser is one rural district using the equipment to share its classes with other districts and enable students to take classes that wouldn’t be available otherwise.

But the success stories are scattered. The majority of school districts don’t even use the videoconferencing equipment — and from fall 2012 through spring 2014, more than half of the students who take Idaho Education Network classes attend just five of Idaho’s 115 school districts.

Are network supporters disappointed? They’re not saying so publicly.

Despite the grim numbers, supporters say the network could help Idaho meet its constitutional mandate to provide a uniform education system. “(This offers) the embryo of that opportunity,” DeMordaunt said.

Will Goodman, state superintendent Sherri Ybarra’s new chief technology officer, says the numbers are better than they sound. There are only so many students who are qualified to take the advanced classes available over the network, and only so many students who can fit them into their schedule. And the state won’t compromise local control to boost enrollment numbers, he said.

So, what about equipment use? That’s another issue. An independent state “service audit” revealed that schools are only sporadically using the network’s pricey hardware, such as HD cameras, flat-screen televisions, projectors, document cameras and video teleconference equipment.

The Otter administration has questioned the report’s accuracy. However, the findings raised a few eyebrows when they were presented to JFAC, the same committee that will hear from Luna on Thursday.

Coming Thursday: Check back at Idaho Education News for full coverage from JFAC.