Idaho is infamous for its dead-last rankings in per-pupil spending.

Every year, newspaper headlines around the state broadcast Idaho’s latest low ranking – but it’s not really news. It’s been the same story for at least a decade.

So it was no surprise when the most recent data from the Census Bureau and the National Education Association pegged Idaho in last place with less than $10,000 spent on each student. The top states spent more than twice that amount.

The numbers seem to paint a dismal picture – that Idaho doesn’t care to invest in its kids.

But the state will be spending a historic amount on public education next fiscal year and already allots about 55% of its budget on K-12 funding – a higher percentage than most states.

And more funds might be on the way. Reclaim Idaho’s Quality Education Act, which will be on the ballot this fall, would increase K-12 funding by $323 million a year (state officials and opponents say the initiative would also repeal 2022 income tax cuts, bringing the overall tax hit to $573 million annually).

District officials and the state teachers’ union say more money is needed to fund salaries and day-to-day operations. And with Idaho’s record-breaking surplus, it seems the state could spare some more change.

However, education reformers argue that more money isn’t the right fix. Idaho’s public education funding formula needs to be revamped first, they contend, so funds can be more equitably distributed to the economically disadvantaged and to low-performing students who need them most.

Basically, the policies that guide how Idaho’s education money is dispensed is like a leaky pipe — more water (funds) would be meaningless without patching the hole (funding formula).

But Idaho administrators say both are needed — more money and a funding formula change.

To further complicate matters, per-pupil expenditure (PPE) numbers seem to have no impact on student achievement on statewide tests like the ISAT, which brings into question whether the number has any significance.

So while Idaho’s last-place PPE ranking is clear, what to do about it is anything but.

For a quick explainer on PPE — what it is and how it’s calculated, check out “Per Pupil Expenditure Explained.”

Amid historic education funding, districts still scramble to make ends meet

Since Gov. Brad Little took office in 2019, he has fulfilled his mission to dramatically increase education funding, pumping $203.5 million into K-12 education and $123 million into the teacher salary ladder. Within his first week of being in office, he said education was his “No. 1 priority for our state budget.”

“I know there’s a strong correlation between our education system and the attractiveness of our state to entrepreneurs and businesses,” he said in his first State of the State address. “More importantly, a strong education system helps ensure we keep our best and brightest right here in Idaho.”

But Idaho’s go-on rate has dropped to 37%, a number that has steadily declined since 2017 – even amid this year’s historic $258 million K-12 funding increase.

Superintendent of Public Instruction Sherri Ybarra touted the record-breaking increase last spring and pointed to how it would lead to bonuses and pay increases for Idaho’s teachers, staff, and administrators, as well as help fund early literacy initiatives like all-day kindergarten.

“I am thrilled that this budget continues to make support for public schools such a high priority,” she said.

But as Idaho’s politicians celebrate the increase, a local district official said it’s still not enough to fund day-to-day education needs.

Scott Maben, the spokesperson for the Coeur d’Alene School District, was preparing one recent evening for a community presentation on a 10-year, $80 million plant facilities levy.

The levy – which goes up for a vote on Aug. 30 – requires 55% support to pass. If approved, most of the money would go toward maintenance and repairs, and 25% would go to improved safety, security, and technology.

Maben said the facility repairs and maintenance are essential and can interfere with learning if not addressed. For example, if an HVAC system goes down during the winter and heat is lost, school would have to be canceled. And such fixes tend to get more expensive the longer they’re delayed, so it’s better to address them early. But how to afford them is another question.

“We don’t have a source of funding for this. The state doesn’t provide sufficient funding for operations and salaries,” he said. “Idaho’s always on the bottom of funding public education in every survey, report and study.”

But Maben is hoping for some more state funding, in light of Idaho’s $1.4 billion surplus.

“A lot of us are looking to the governor’s office and the Legislature to make those one-time investments,” he said.

Lisa Arnold, superintendent of the Lakeland Joint School District, also lamented the lack of adequate state funding.

“On average, the state only covers about 70-75% of salaries and benefits,” she said. “Local patrons have had to support the rest through levies, and it’s the same throughout the state.”

Lakeland has a $42 million general fund budget, supplemented with a $9.5 million levy that becomes about 22% of the district’s budget.

Last year, 89 of Idaho’s 115 school districts relied on local supplemental tax levies, with patrons paying out a record $218.2 million. Idaho’s nearly 80 charter schools are not allowed to levy taxes.

Bonds are not accounted for in PPE calculations but the funds they generate are essential to learning

Student safety concerns and population growth are putting the squeeze on districts to build new schools and update existing ones, expenses the state doesn’t pay for. Districts must ask local taxpayers to approve bonds — and that doesn’t always happen because typically a two-thirds supermajority is needed for the long-term debt.

The Middleton School District is seeking a $59,435,000 school bond on Aug. 30 to build a new elementary school and two other projects – its Mill Creek Elementary is at 123% capacity, and hallways, the staff lounge, the lunchroom, the music room, and essentially any other available space is being used for instruction. But similar bonds have failed regularly in the community.

The Idaho Falls School District is floating a $250 million bond for new and updated schools — the largest proposed bond in Idaho history. Superintendent James Shank said the continued population growth in the district has led to overcrowded elementary schools.

“Bonds are important for school districts because they’re really the only way to fund substantial capital projects,” Idaho Falls spokesperson Margaret Wimborne said. “We do receive money through the lottery for maintenance, but it’s just not enough money to build a new school or do extensive renovations and updates.”

Building and maintenance costs may seem to have a secondary impact on learning (when compared to teacher salaries, for example), but district officials say that having a safe, warm, clean, uncrowded classroom is essential.

Yet it’s worth noting that any money spent on what are called capital improvements are not considered in per-pupil expenditure calculations. Part of the reason they’ve been excluded is because they can skew results. If a district builds a school one year, their PPE number would skyrocket and not accurately represent the average spending on students in a typical year.

That example shows just one way in which PPE numbers don’t necessarily show the whole picture of money spent on students in a given district.

But that doesn’t change the fact that Idaho still lags behind on PPE.

Reclaim Idaho and IEA advocate for more education funding

Reclaim Idaho hopes to pull the state from its last-place standing by increasing taxes on corporations and top income-earners. The group’s Quality Education Act initiative will appear on the ballot this fall.

Reclaim co-founder Luke Mayville said the $323 million in proposed tax increases would increase per-pupil expenditure by over $1,000 per year.

“We believe PPE is an important measure because student achievement depends on strong programs and it depends on qualified teachers and support staff. All of this costs money,” he said, pointing to Idaho’s unfilled teaching positions and Idaho’s dead-last ranking for support staff wages.

“We need a system that works to create equity for students no matter what their background is or what their zip code is,” — Mike Journee, Idaho Education Association spokesman

The Idaho Education Association has publicly endorsed the initiative and would like to see a boost in student spending.

“PPE is one metric that we look at here in Idaho that illustrates the lack of overall funding for public education,” IEA spokesman Mike Journee said. “Our members would love to see steps toward fully funding the public education system in a way that creates great schools across the state.”

He said ballot initiatives, bonds, and levies are band-aids that only temporarily alleviate Idaho schools’ budget needs.

“Those that rely year to year upon whether or not there’s a budget surplus or if voters approve a bond – that’s no way to properly fund the public education system,” he said.

He also added that the funding formula needs to be more equitable.

“We need a system that works to create equity for students no matter what their background is or what their zip code is,” Journee said.

Idaho’s funding formula is not equitable, state and national organizations say

Idaho ranked No. 43 in the nation in terms of equitable funding measures, according to EdWeek’s most recent Quality Counts report.

EdWeek’s equity analysis considered these two questions, according to its website:

- To what degree does funding for property-poor districts differ from that of their wealthier counterparts?

- How different are the spending levels of the highest- and lowest-spending districts?

Overall, Idaho earned a B grade for equity (which still put it below most states) and an F grade for spending. Those averaged out to a D for school finance.

Idaho’s education finance inequity has caught the attention of the Reason Foundation, a nonprofit libertarian think tank. Idaho is one of eight states the organization pays special attention to due to their funding systems.

“All school finance formulas are bad in some ways, but Idaho’s is especially problematic,” — Aaron Garth Smith, director of education reform for the Reason Foundation

“All school finance formulas are bad in some ways, but Idaho’s is especially problematic,” said Aaron Garth Smith, the organization’s director of education reform.

Idaho’s public education finance formula doles out money equally to districts based on their average daily attendance (which has temporarily been switched to an enrollment-based model, at least through this school year), grades served, and staff hired.

Smith, who wrote a column about Idaho’s need for education finance reform last year, said the formula ignores student need. The equal payments the state issues out are not necessarily equitable.

“In Idaho, what a district generates in terms of funding is largely driven by local property wealth and factors that favor districts with property wealth,” he said. “One good example is the more experienced teachers you have, the more funding that will deliver. On paper that might sound fair and equitable, but in practice the wealthier school districts have more experienced teachers, so it’s diverting more dollars to them.”

Wealthier districts also generate more property taxes and can absorb a bigger bond issue without as much of a burden on taxpayers. Levies and bonds may also be easier to pass in those districts. But the state funding formula does not take such economic differences into account.

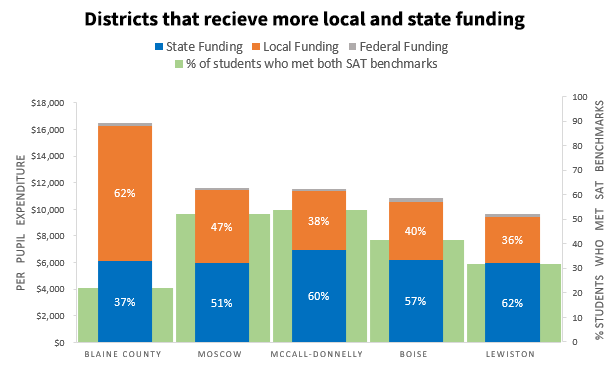

In the 2021 fiscal year, for example, the state allotted $19.4 million to Blaine County School District, home to wealthy communities like Bellevue and Ketchum. The district received another $32 million in local funding, which made up a majority (62%) of its overall budget.

Other districts don’t have such local resources to pull from. Some have none. Others, like charter schools, are not allowed to levy taxes.

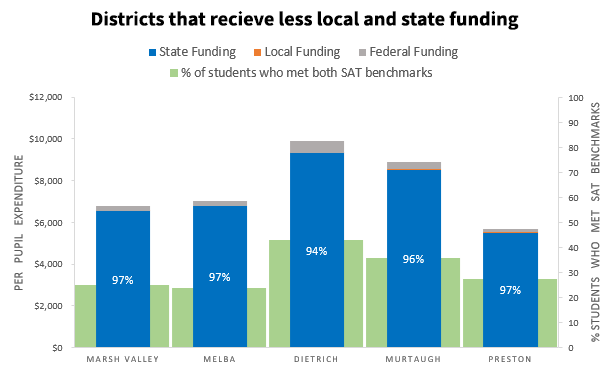

Wealthy school districts tend to get the most money, but don’t always show greater student achievement

The charts below (which use 2020-2021 information) show how wealthy districts tend to get more money from both state and local sources and therefore have higher per-pupil expenditures. But SAT benchmark percentages (just one measure of student success) are not always better. For example, the Blaine County district infused its 2020-21 budget with $32 million in local dollars. Yet, its average SAT benchmark percentage fell below that of the five small districts in the second chart who received less than 1% of their budget from local sources.

That’s why Smith argues that reforming Idaho’s funding formula is more pressing than boosting student spending levels. In essence, pouring water into a leaky pipe won’t help until the hole is patched.

“People can get bogged down in how states compare to each other in terms of funding,” he said, adding that that leads to putting “more money into a bad funding formula.”

Another organization argues that Idaho’s economy is the main issue. From 2012 through 2018, the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation implemented a campaign called “Don’t Fail Idaho,” which aimed to “raise awareness that improving education is critical for our children’s future and inspire the prioritization of actionable and timely solutions.”

As part of that campaign, the foundation created an information packet called “ReThink Funding.” It examined data about how Idaho was financed and reached the conclusion that, “If Idaho fails to grow its economy relative to the population of school-age children, the state will probably continue to rank low on per-student spending.”

“Policymakers face a ‘chicken or egg’ dilemma,” the packet reads. “Should Idaho put a higher proportion of the state’s available dollars into education in the hope that it will improve the economy? Or should Idaho focus on funding activities that will grow the economic pie so that there will be more dollars for education? Or both?”

Idaho doesn’t have lucrative economic drivers, like California’s Silicon Valley tech industry or Colorado’s recreational marijuana industry, which is just one reason why comparing Idaho’s PPE to other states creates an apples-to-oranges false equivalence.

Administrators push for a unified front ahead of the next legislative session

At last week’s Idaho Association of School Administrators conference, education leaders told attendees that they needed to unify their voices on the funding formula front — and soon. The group aims to create five standards that would establish non-negotiable criteria for any new funding formula. The IASA believes that if every superintendent in Idaho supports the standards, then the Legislature will be more likely to consider and adopt them.

“We have to be united,” Blackfoot School District superintendent Brian Kress said. “We are powerful … if we come together and speak with the same voice.”

But unity isn’t a given. Kress recalled past years when administrators got into yelling matches over proposed funding formulas. The problem was that those past proposals created “winners and losers” — some districts gained significant funding and others lost significant funding. That didn’t seem fair.

Kress said the answer is not taking the same pie, an identical amount of funding, and cutting it up in different ways, by changing the formula. The answer is getting more pie and cutting it up in different ways.

“Legislators can’t create a new funding formula without more investment in public education,” he said.

A draft is in the works, Lake Pend Oreille School District Superintendent Becky Meyer said. The IASA plans to send that out to administrators and get feedback, then have a final draft of the standards ready in time for the Idaho School Boards Association conference in November. IASA hopes to get ISBA on board with the standards, as well as principals’ associations and the Idaho Education Association.

If legislators decide to tackle a funding formula this session, education leaders want to be ready — there’s a lot at stake.

And there’s another crucial question education leaders need to answer: What would it cost to fully fund Idaho schools? They hope to work together to come up with a number for legislators.

Does PPE contribute to student achievement?

By one measure, student achievement is on the rise in Idaho.

EdWeek’s recent Quality Counts report ranked Idaho as No. 17 for student achievement among all states and the district of Columbia.

“That’s particularly encouraging considering that our ranking for 2016 (released in December 2015) was 31st in the nation,” Ybarra said in a 2021 press release. “And it’s gratifying because the rank is largely based on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the only assessment that gives us apples-to-apples comparisons with other states.”

But other measures – like Idaho’s falling go-on rate and slipping SAT benchmark percentages – show that Idaho students have room for improvement.

And Journee pointed out that the state is losing educators, partly due to frustration over pay and benefits (though both were boosted in the 2022 legislative session).

It’s hard to definitively state whether, on a state level, PPE impacts achievement. It’s equally difficult to assess on a district level.

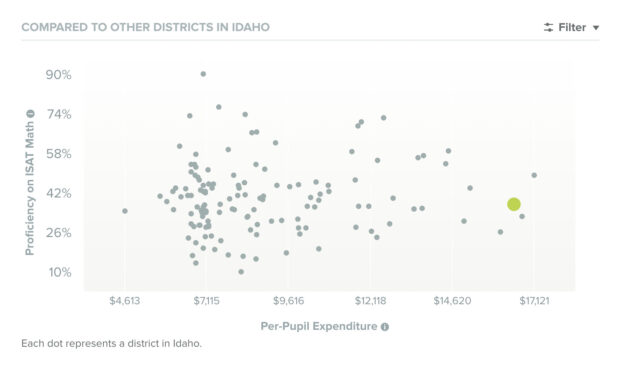

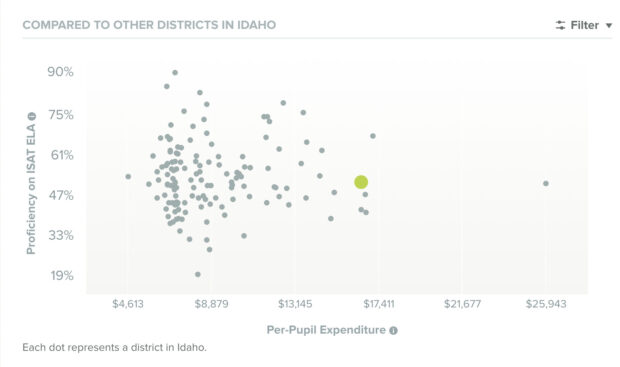

Data from Idaho Ed Trends shows that proficiency levels on the ISAT math and ELA exams did not correlate with PPE. For example, the charts show how Blaine County’s Wood River High School (the green dot) has very high PPE but average ISAT scores.

In its information packet, Don’t Fail Idaho raised the question: “If Idaho elects to boost per-student spending, how would schools make the new money matter?”

“Evidence and experience demonstrate that additional dollars alone do not guarantee improved results,” the packet reads. “Spending more money the same way – business as usual – has shown limited success elsewhere.”

Dan Nicklay, the principal of Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy, would agree.

“There’s very little evidence to support that more money makes better education,” he said.

He said that a lack of appropriate funding is not the problem – outside forces are.

“The public does not value education as highly as they claim to, and I’m not talking about monetarily,” he said. “Teachers don’t get the respect that the nobility of their profession warrants … It’s never a thankless job, but it can feel that way sometimes.”

Don’t Fail Idaho, Idaho Education News, and Idaho Education Trends are funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation. Data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.