EDITOR’S NOTE: Eleven Idaho schools are launching on an experiment this fall. They are using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools. This is the first of a series of stories on the grant recipients.

Kuna Middle School’s Chromebook era is off to a sluggish start.

The school has one of the devices — small, lightweight and relatively inexpensive laptop computers — for each of its 800 students. But the chargers haven’t shown up yet, so students won’t get their individualized Chromebooks until Sept. 24, more than a month into the school year.

But Kuna Middle School is taking a long-term view. The school has a 10-year budget blueprint that spells out how computing devices can be a fixture in the classrooms. And the school has ambitious goals to improve math and writing test scores, using the Chromebooks and related curriculum as the impetus.

It all ties into the middle school’s central goal: to develop competitive and prepared high school freshmen. “This is just one more way that they will become competitive,” Principal Deb McGrath said.

Of the state’s 11 technology pilot grant recipients, Kuna is collecting the largest sum of money — $891,200.20, or nearly 30 percent of the $3 million that was up for grabs. Of the 81 schools that applied for technology money, no school asked for more than Kuna Middle School.

An attempt to bridge gaps

Kuna is one of the Treasure Valley’s growing bedroom communities, but 44.3 percent of the middle school’s students qualified for free or reduced lunch in 2012-13. The income gap has been evident when students were allowed to use devices in class; some had smartphones, others had texting phones, others were empty-handed. “We’ve got the very wealthy to the homeless, and everything in between,” says math teacher Shelby Harris.

Test scores, meanwhile, illustrate student achievement gaps.

A three-star school in Idaho’s latest five-star ratings, Kuna Middle School is underperforming in several areas on math and writing assessments. “The identified learning gaps are predicted to get wider with the

implementation of the more rigorous (Common Core standards),” the school wrote in its grant application.

With some writing proficiency scores ranging from 53 to 67 percent, the school hopes the Chromebooks will help students reach the 85 percent mark.

The goal is to use the Chromebooks to streamline and improve the writing and editing process. Students will no longer write drafts longhand — then get parceled out to work on the school’s existing banks of PCs. Writing on Chromebooks, students will be able to edit as they write, collaborate with their classmates, and receive quicker feedback from teachers.

Kuna also hopes to hit 85 percent proficiency in math; Hispanic students, economically disadvantaged students and students with disabilities have fallen short of this benchmark. Here, the goal is to use the Chromebooks to individualize learning — to give students detailed feedback about what they’re getting right and wrong, and providing them the extra practice and training they need.

In this discipline, Chromebooks have already been in use in Kuna.

Building on experience

In Harris’ accelerated seventh-grade math class, she sees the need to tailor learning to students. She sees students who can handle most of the rigors of an accelerated course — until they have to work with fractions or complete long division. “And then you get the tears.”

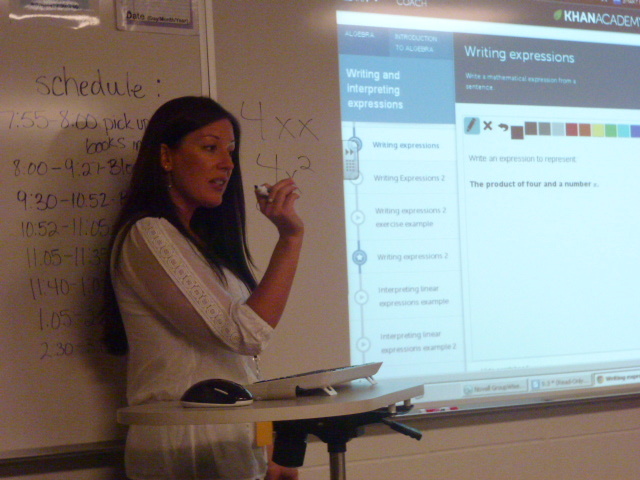

Harris is a Chromebook early adopter, and a believer. Through a grant from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation, Harris began using Chromebooks in her classroom in March — and using online lessons from the Khan Academy. (Harris’ work with the Khan curriculum will be highlighted Friday night in “Teach,” a documentary on four educators, airing nationally on CBS.)

The Khan curriculum allows students to work at their own pace and get extra help where they need it. There’s less, ‘I’m bored,’ and less, ‘I’m lost,” said Harris.

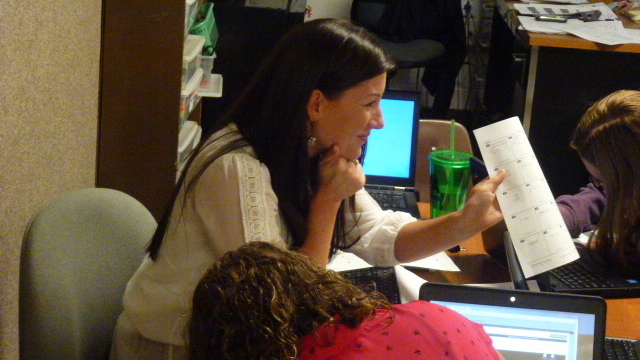

Teachers are responsible for tailoring assignments, Harris said, but they also get more small-group time with students.

During one recent class, Harris spent part of her time with three students, helping them set individualized goals. Then Harris moved to another group; as a circle of nine students sat at desks or on the floor, she spent 20 minutes working in front of a smartboard, explaining math expressions. Meanwhile, the rest of her 23 students worked individually or in small groups, using Chromebooks the school received last spring. In these small groups, some students are more likely to speak up. Others, meanwhile, know they can’t afford to zone out.

Harris admits the transition to Chromebooks was tough — but, in some ways, easier for her students. Some students, not even necessarily her best math students, stepped up to provide tech support to their classmates. And the classroom results were encouraging enough that Harris’ fellow teachers wanted a shot at using Chromebooks, and encouraging enough that the school used Harris’ work as the template for its technology pilot grant application.

That didn’t surprise Harris at all.

“There’s a lot of energy in the building, and a lot of tech-savvy staff.”

A scalable model?

Kuna officials believe their Chromebooks model can be replicated in other schools.

But it won’t come cheap.

The two-year grant costs come to $530.48 per year, per student, largely for equipment purchases. But the grant application also calls for spending $234,000 on professional development and staffing — including an existing technology integration specialist, a district job that now will be funded with grant money.

Kuna started out ahead of the game, McGrath said, with infrastructure and staffing in place to support a pilot. In other schools, she said, a program could prove to be more expensive.

Eventually, Kuna expects its costs to level off. Over 10 years, the school anticipates costs of $179.12 per year, per student, and that includes buying a new round of devices in Year Six.

McGrath is focused on the Sept. 24 rollout. And Oct. 1, when students get to show off their Chromebooks during conferences with their parents and teachers. But she sees this as the first step in a transformation. “I think it’ll become how we all do business.”

Disclaimer: Idaho Education News is funded by a grant from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation.

More reading: How Kuna Middle School will seek to fuse new technology with new Common Core standards.