Christian Garcia can only speak to his family in Venezuela when both the power and Internet are working at his home of San Cristóbal. Typically, they talk about twice a week.

Those calls are a lifeline for Garcia, a College of Idaho student who hasn’t been able to visit his family for four years due to the country’s economic and political collapse. And as coronavirus threatens Garcia’s family in both hemispheres, the calls have been emotional.

On March 13, the first cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in both Idaho and Venezuela. Garcia’s spring semester classes were moved online, his spring break plans cancelled, and his travel off campus restricted by a statewide stay-at-home order.

In Venezuela the government restricted travel between states, separating Garcia’s parents from one another. Neighboring Colombia closed its borders, cutting Garcia’s family off from both a vital food supply, and their access to whatever money he can send home.

Stuck in his room at the College of Idaho, unable to get on a flight home or even kill time at the closed campus gym, Garcia feels stressed — and powerless.

“I was talking to my mom yesterday, and she was just crying,” Garcia told EdNews in an interview last week. “It’s hard to see my mom like that.”

When coronavirus threatened Idaho, the College of Idaho asked its nearly 700 student residents to move off campus if they had a permanent place to live. Almost 200 students are still there. Most, like Garcia, are members of the school’s large international student body.

“For many of these students, they come from places where they can’t get back, or they literally don’t have a home to go to,” said Jen Nelson, director of residence life at the college.

Some tried. Nelson said some five students tried to buy tickets home, and even showed up at the Boise airport for their flights, only to find their home countries had closed their borders.

“To be honest, most of us don’t have places to go,” – Yassir Mushir, international student from Iraq

Stranded in Caldwell, these students face social isolation, the upheaval of their studies and social lives, and the stress of a pandemic far from home.

“In situations like this, being far away from your family is really challenging. Emotionally, it will really drain you,” said Yassir Mushir, a student from Iraq. “You think a lot about your family, and at the same time you have to be worried about your classes and people around you here. Balancing that dynamic is challenging.”

Nelson eyes the new social environment like a puzzle. Her job, which typically means gathering students together as a community, now means building community from a distance.

The nearly 200 students on campus have been moved into private rooms in three of the college’s residential buildings. The idea was to spread students out enough that they have social distancing space, while also consolidating campus resources. Students can access three meals a day from the residence halls; talk in small groups and from a distance, and venture outside for fresh air or groceries.

The College of Idaho’s counseling staff is still connecting with students virtually, Nelson said, and some campus clubs are working out ways to keep meeting.

She’s trying new ways to build a spread-out community, from campus art projects to using a chat function on Netflix and organizing workouts. Her staff is turning to the students for their ideas on how to stay connected.

“For people, just in general, this whole situation is very scary,” Nelson said. “Maintaining that sense of community, that you belong somewhere and that people care for you, that’s one of the best things we can do to alleviate any fear or concerns our students have.”

While both students and the college are working out the kinks of their new realities, a longer-term question lurks: What are students going to do this summer?

Garcia had planned to go back to Venezuela. Now he worries that if he makes that trip he won’t be able to come back to the College of Idaho in the fall. Still, he said, it’s hard to think that far ahead.

“Let’s hope this only lasts a couple of months,” he said.

Mushir can’t go home for the summer. If he does, he risks losing his visa. He worries about his father, a doctor who is still working in the hospitals, risking exposure to coronavirus so he can reach his patients.

This summer, Mushir had planned to return to work at Roundup River Ranch, a Colorado camp for kids with serious illness. This would have been his second year as a camp counselor.

That’s been cancelled, too.

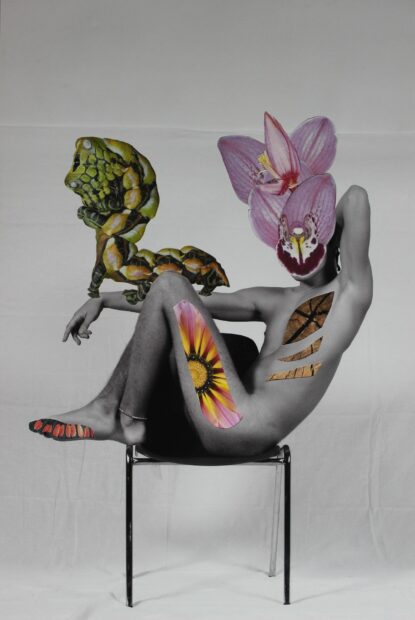

In the face of uncertainty, Garcia and Mushir go to their online classes. They read books. Make art. Listen to podcasts. Do puzzles.

It helps, Mushir said, to talk to friends like Garcia, and be surrounded by other students in the same situation.

“It’s very interesting because our group is very diverse. Everybody is from a different place,” he said. “But we always have something to talk about. We support each other a lot.”