Here’s something you probably already know: High-quality preschool provides academic and social benefits for low-income children.

Here’s something you may not know: Preschool provides benefits, albeit smaller ones, for middle-class kids too.

And yet, though most countries with developed economies offer public preschool as a standard benefit to all 4-year-olds, America does not. Instead, low-income parents here scramble for scarce public spots while middle-income parents scrounge to pay for increasingly costly private preschool.

“Only very wealthy people can afford current decent care and education (for young children),” said Richard Brandon, a political scientist recently retired from the University of Washington and co-author of a 2018 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report on financing early education. “Very few can afford what we estimate is the cost of quality care.”

Brandon and his co-authors peg the full-time, full-year cost of sending a child to a preschool with ample, safe facilities, a developmentally appropriate curriculum and well-paid teachers at $13,655 per child. That’s about $1,000 more than the national average per pupil spending in K-12, as calculated by the National Center for Education Statistics.

It’s also about 16 percent of an $88,000 annual income, more than double the 7 percent figure the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services deems “affordable.” Yet, with few exceptions, families earning $88,000 a year — right in the middle of the middle class — get no government help to cover the cost of educating their 4-year-olds.

The vast majority of government funding for early childhood is meant to help children living in poverty overcome the stubborn and troubling academic achievement gap that separates them from their wealthier peers. Despite this focus, there’s not enough public money budgeted to provide preschool to all the children who qualify for aid, let alone help children from higher income families.

The vast majority of government funding for early childhood is meant to help children living in poverty overcome the stubborn and troubling academic achievement gap that separates them from their wealthier peers. Despite this focus, there’s not enough public money budgeted to provide preschool to all the children who qualify for aid, let alone help children from higher income families.

Ignoring the roughly half of America that is middle class — a group which includes households earning about $44,000 to $132,000 — won’t help improve the education system, Brandon argues.

“The biggest problem in education is crushing mediocrity,” he said. “If you want kids to be doing well and you want to move the middle upward and not just move the low end to the mediocre middle, you’ve got to help everybody.”

Meanwhile, new evidence suggests that the most cost-effective state preschool programs for poor children include all children. Universal programs have a significant positive effect on the reading scores of children from low-income homes, while programs targeted only to poor children do not, Dartmouth College economist Elizabeth Cascio found when she analyzed kindergarten performance data.

Since many families will still find a way to pay for some preschool, universal preschool is “essentially giving a cash transfer to middle-class families,” Cascio said.

“But,” she added, “what if higher-income kids are needed to make pre-K more productive for disadvantaged kids?”

While existing economic segregation means a universal preschool wouldn’t serve a perfect mix of lower- and upper-income families, it would be more mixed than the current system, which clusters children living in poverty. And in states where universal preschool is offered, Cascio found, middle-income parents take advantage of it.

In contrast, attendance at government-funded preschools is the norm in many countries. Four-year-olds are enrolled in school at an average of rate of 87 percent among the world’s 35 developed economies tracked by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, an international cooperative meant to help member countries grow their economies. The United States is a founding member, but just 66 percent of 4-year-olds were enrolled in school here in 2015. Most other OECD countries also spend more per preschooler than does the United States.

The economic incentive for middle-class American parents to send their child to a free public preschool is clear. Most parents don’t spend the $13,655 a year Brandon and his colleagues estimate would buy the best-quality preschool experience, but middle-income parents are spending hefty percentages of their paychecks on preschool. The cost comes to 9 to 12 percent for families earning between $50,000 and $100,000 a year, according to calculations by Grover “Russ” Whitehurst, a senior fellow at the nonpartisan Brookings Institute.

In 2016, Whitehurst found, parents spent an average of $7,053 on preschool fees for their 4-year-olds.

Parents’ willingness to spend so much on preschool, even for part-time slots, could be seen as evidence that they don’t need government subsidies, Whitehurst writes in a recent report on the market price of early education.

Lawmakers from both parties, experts across the political spectrum and most educators agree. Given limited dollars, they say, funds should be directed to the children who need the most help.

“There really is an argument to be made for targeting the lowest-income kids,” said Kris Perry, president of the lobbying arm of Save the Children. “Middle-income kids are going (to preschool). They don’t need help really.”

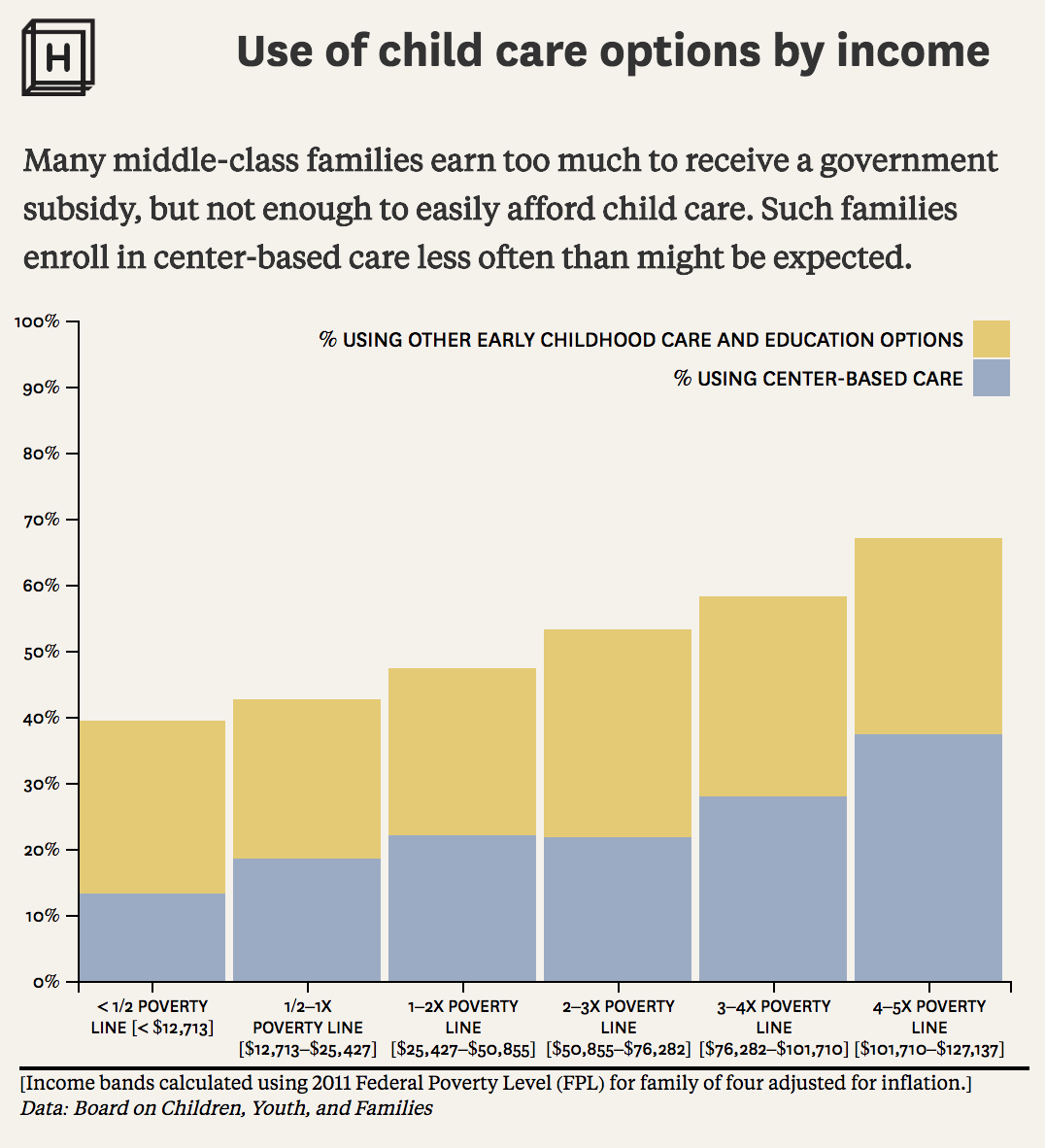

Whether or not you think the middle class needs help to afford preschool depends on your perspective. American children from families earning between two and three times the federal poverty level, about $51,000 to $76,000 for a family of four, enroll their children in early childhood education programs located at standalone or school-based centers at about the same rate as families earning one to two times the poverty level, about $25,000 to $51,000 for a family of four, according to the National Academies of Sciences report. (Ranges are based on the 2011 poverty levels used in the report and have been adjusted for inflation.)

In other words, lower-middle-class families use preschool at the same rate as low-income families, despite using more child care overall.

That’s notable because the expectation would be that middle-income families, like upper-income families, would be more likely to use center-based care, which is widely regarded as offering the highest quality, said Brandon. Instead, at the income level where government aid drops off, the percentage of families using preschool centers drops off as well.

Families earning three to four times the federal poverty level, or $76,000 to $102,000 for a family of four, also use less-than-expected amounts of center-based care. It’s not until family incomes reach the top of the middle-income range that more than half of families choose center-based care. This is likely an indication that they are finally making enough to consider the cost of center-based care affordable.

Brandon has seen the same trend for the past 30 years. “It’s an indication that they can’t afford center-based care,” he said, “not that they don’t want it.”

Most of the benefits of formal preschool programs can be attributed to well-trained, well-educated teachers. Research shows that schools with high-quality teachers produce the best academic and social outcomes. The best teachers encourage play, exploration and friendship, while introducing pre-academic skills through picture books, science experiments, math games and other activities.

Yet for all that work, most private preschool teachers make near-poverty wages. The average wage for preschool teachers who are not employed by a public school system is $13.98 an hour or $29,080 a year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“To the extent that (child care) is at all affordable to middle-class families, it’s on the backs of providers who are then living in poverty,” said Katie Hamm, vice president of early childhood policy at the progressive Center for American Progress.

For child care workers overall, including those in home-based child care facilities, the situation is even more dire. Nearly half, 46 percent, qualify for public assistance such as Medicaid or food stamps, according to the early childhood workforce index published by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. Among preschool and kindergarten teachers, 34 percent qualify for some form of public assistance.

“Which means,” Hamm said, “the government is subsidizing middle-class child care anyway.”

The only preschool teachers who make what could be considered a middle-class wage work at public schools. Public school preschool teachers make an average hourly wage of $24.06 or $50,040 a year. But only five states, and a handful of cities, offer free public preschool programs that accept children from middle-class households.

Without new government funding to offset the cost, higher teacher wages would push preschool out of reach for even more families. According to a calculator released by Center for American Progress, paying preschool teachers on par with K-12 teachers, a move many experts say would raise preschool quality, would push the annual per student cost in many states up over Brandon’s $13,655-per-year estimate.

A few places around the country are attempting to expand subsidized preschool to middle-class families. In 2014, New York City made preschool universal in its public schools, drawing large swaths of middle-income 4-year-olds. Seattle, Los Angeles, San Antonio and Boston are among a growing group of large cities adding preschool to their K-12 systems.

States are moving slowly in the same direction, more than tripling their spending on preschool since 2002, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research. The District of Columbia, Florida, Vermont, Oklahoma, Wisconsin and West Virginia even offer universal preschool access. (Per pupil spending has actually gone down nationally in inflation-adjusted dollars over the same time period, sparking concerns about preschool quality. Differences in per pupil spending by state vary widely.)

Still, just 1.37 million children attended public preschool during the 2017-18 school year, about a third of the number who attended public kindergarten, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

A scattering of other efforts are aimed at helping middle-class families afford preschool. A bill in Colorado would defray child care costs for families earning up to $150,000 a year by offering them a tax writeoff. The bill’s proponents argue that such assistance would help continue the state’s current economic boom by keeping relatively high-earning parents in the work force.

“When people see a six-figure income, it seems like that should be a family who should be able to afford care,” said Lauren Freemire, the Colorado manager of state government relations for the Save the Children Action Network. “But the cost of living in Colorado is going up. Wages have remained flat. The choices are between ‘Should I stay at my job?’ or ‘Should I stay at home with my child?’”

Keeping parents in the work force and offering more kids a chance at a high-quality preschool education would have a “two-generation impact,” Freemire argues.

Nationally, voters seem to think additional assistance for the middle class is warranted. Seventy-four percent of Republicans, 79 percent of independents and 97 percent of Democrats said there should be increased funding for child care that directly supports greater access to quality programs for low- and middle-income children, according to 2017 poll data commissioned by the First Five Years Fund, an advocacy organization dedicated to improving early education for disadvantaged children. Fifty-seven percent of respondents even told pollsters they would have a more favorable opinion of their member of Congress if he or she supported increased funding.

Voters are also in broad agreement that the government should do more to help the middle class: 51 percent of Republicans and 70 percent of Democrats think the federal government does too little to help the middle class, according to a 2018 poll by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center.

Nonetheless, neither Republicans nor Democrats at the national level are arguing that the United States should match its international counterparts and provide the same standard of education for its 4-year-olds that it provides its 5- to 18-year-olds.

It would be an expensive gambit. The National Academies of Sciences report estimates the total cost would run to $140 billion a year. Evidence suggests such an investment would pay dividends running to the trillions of dollars in money saved on social services and raised through income taxes on higher incomes, but political will is lacking.

“The political will is really not terribly informed by evidence,” Save the Children’s Perry said. “It’s more informed by what’s politically possible.”

And even more informed, perhaps, by what politicians think is politically possible.

This story about preschool was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.