Lynn Manning John remembers learning Idaho history in a Boise fourth-grade classroom. There were lessons about Sacajawea and Chief Joseph. But there were no lessons about modern Native American people, like herself.

Her classmates were fascinated by her.

Kids would come up to her at recess and ask if she was “a real Indian” and if she really came from a reservation. When she said yes, one kid would gloat: “I told you so!” And they’d run off.

“I was a novelty,” said Manning John, a Shoshone-Paiute tribal member. “I was a dare: go up and talk to the Indian girl.”

The alienation she felt there stung even more, because the Boise, Bruneau, and Mountain Home areas are her tribes’ homelands.

She sympathizes for her family members who still live in the area.

“I can only imagine what their experience has been being invisible in Boise, which is our ancestral homelands,” she said. “Unless they stand up and assert themselves as a Native person, they’re probably just missed.”

Native American people frequently talk about that feeling of invisibility, especially in classrooms. And it’s a nationwide phenomenon.

Shelly Lowe, Chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities and a Navajo tribal member, travels the country and sees it often.

“I run into people all the time who tell me they didn’t know Native Americans still existed in this country,” she said. “And it’s because we don’t teach a history that accurately tells individuals who Native people are and how we are still here, how we are a contemporary people.”

“I run into people all the time who tell me they didn’t know Native Americans still existed in this country.” — Shelly Lowe, chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities and a Navajo tribal member

And when the history is told, it’s not from a Native perspective. To combat that erasure, there’s a need for more Native American curriculum, teachers, and education leaders.

But in Idaho, there are only four Native American administrators out of 1,280 (or 0.3%). Comparatively, there are 3,146 Native American students out of 312,000 statewide (or 1%).

Efforts to diversify the administrator pool seem to be in a holding pattern.

Increasing the number of Native American administrators was once a statewide goal, but was one of many initiatives dropped from the Indian Education Strategic Plan in 2021. Leaders of a University of Idaho program that focuses on getting more Native American teachers in the classroom aspire to add an education leadership component someday. But that is a long-term goal, as it will depend on securing funding from grants.

For now, the state’s few Native American administrators are a rarity.

The same is true in Nevada, where Manning John is now the vice principal of the Owyhee Combined School, a public school on the Duck Valley Reservation that serves Idaho tribes and students. She’s one of two known Native American principals in the state.

Part of the reason for the scarcity of leaders, she suspects, is education’s complicated history with tribes.

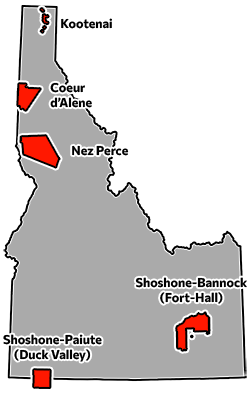

From three of Idaho’s five reservations, Native American principals share what it’s like to be among the few.

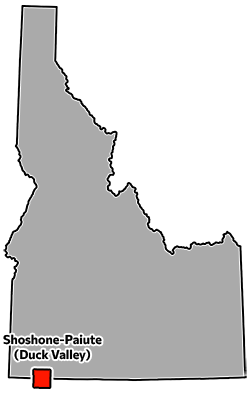

- On the Duck Valley reservation, Manning John is countering education’s toxic past with new hope for the next tribal leaders

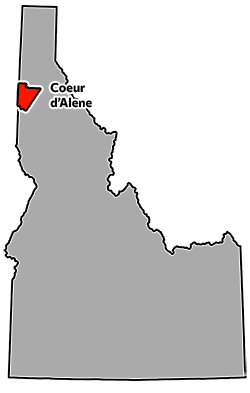

- On the Nez Perce reservation, Principal D’Lisa Penney says acknowledging history and building a tribe’s future is a “dual dance”

- On the Fort Hall Reservation, Matt Wilson went from being a high school dropout to a high school principal

On the Duck Valley reservation, Manning John is countering education’s toxic past with new hope for the next tribal leaders

The Duck Valley Reservation is a land of binaries.

It is home to both the Shoshone and Paiute tribes, and is located in both Nevada and Idaho, crossing the state line.

“The line doesn’t matter in our community,” Manning John said. “It’s only when you leave the reservation that Idaho begins or Nevada begins.”

The community, which is about 100 miles or more from a major city in any direction, is so remote that it’s like an island nation. In some ways, that isolation has protected the tribes’ culture and identity.

“It’s the only place in the world where being Shoshone-Paiute is normal,” Manning John said. “Duck Valley is just really unique and dynamic and amazing because of that.”

There, people combine words from the English, Shoshone, and Paiute languages — their own unique version of Spanglish. When they leave the reservation and say phrases like “Brrrrr! It’s cold!” in their native tongue, they’re surprised to see the look of confusion cross people’s faces.

Away from Duck Valley, they become minorities for the first time.

At the community’s only school, the K-12 Owyhee Combined School, the dualities continue — its hallways hold both a dark history and a brighter future.

Once a place where students were taught to “become white,” it’s become a place to celebrate culture. Tribal elders provide twice-weekly Shoshone and Paiute language classes. And on certain days, students and staff wear their beadwork or ribbon skirts.

But it wasn’t always that way.

Some of the school’s staff members are former students, and they still have pencil tips embedded into their scalps, remnants of teachers who would violently poke them for speaking their native language.

Back then, it was just a K-6 school, and students were punished for bringing in their Shoshone-Paiute culture and language.

“They were not allowed to come through the doors as a full person,” Manning John said. “They were expected to shed their nativeness in order to become a student.”

Progress since that time has been steady, but it’s also been slow. It was only two months ago, for example, that Manning John got the district to rescind its English-only policies that were still in place.

And Manning John has had to combat a sense of distrust that some Native Americans hold toward public education — a feeling she understands.

A complicated history and a dedication to change

As a child, Manning John loved school — and she was good at it. Her peers teased her for being a standout student and called her “white.”

Historically, excelling in school was the same as becoming assimilated — becoming culturally white in the process, Manning John explains.

“It was moving away from your tribal culture, language, and traditions, and it was looked down upon in tribal communities,” she said.

She is speaking to the history of boarding schools that aimed to assimilate, weaken, and oppress Native Americans. But even day schools and public schools, like the past version of Owyhee Combined, inflicted trauma on tribal kids.

That history has soured some Native Americans on public education, which they have come to see as antithetical to their culture and identity.

“Kids can sometimes be reluctant to want to do well for fear of being ostracized within the community,” she said.

Manning John’s own love of learning came in spite of the scars her family carries from boarding schools.

Her maternal great grandmother, Marjorie Sam Kelly, was forced to attend Carson City’s Stewart Indian School, likely sometime in the 1920s.

At the time, hygiene standards were poor, and infectious diseases spread rapidly. While at the school, Kelly went blind. The reasons why are unclear: was it from the shared towels? Was it the iodine put into her eyes to rid her of infection? Nobody knows.

But the fact is, Kelly lost her sight. It meant she couldn’t participate in the afternoon’s manual labor — domestic work, ironing, cleaning, and cooking.

So, she was sent home where she could speak her native Paiute language fluently, with her connections to culture and tradition still strong, and she was able to pass that knowledge down to her daughter — Manning John’s mother.

In that way, a lifelong disability was better than more time spent in the boarding school.

But, as is common, Manning John also knows those who had positive experiences at boarding schools.

Her paternal grandfather was a student at Sherman Boarding School in Riverside, Calif., where he learned to become a mason and a mechanic. When he returned to Duck Valley, he was able to open a service station and become a business owner.

And her mother, who taught at Owyhee Combined School until retirement, also instilled in her a love for education.

“This is my home. This is my community. These are my people. The students … are the future of my tribe.” — Lynn Manning John, vice principal at Owyhee Combined School and a Shoshone-Paiute tribal member

It inspired Manning John to start her own journey to becoming an educator, which took her away from Duck Valley as she earned her degree and gained classroom experience. And then she decided to take it a step further, becoming first a program administrator, then a vice principal.

She never knew a Native American education leader growing up, and she wanted today’s kids to be able to see that, to have their eyes opened to another view of education — one with a place for them, their languages, their culture, and their identity.

So while Manning John said she feels burdened by the knowledge of education’s troubling history, she also feels empowered to use education as a tool for good.

She came back to the reservation in 2014, and she said she’s never leaving.

“Although we might venture out, coming home is in our blood,” she said. “This is my home. This is my community. These are my people. The students … are the future of my tribe.”

And leaders like her, who are well-versed in the traumatic history of Native American education in the United States and who are part of their tribal communities, are making a difference.

“The lens through which I view education is (being) very much aware of the history of Indian education, but also very much in a position where I can influence change,” she said.

On the Nez Perce reservation, Principal D’Lisa Penney says acknowledging history and building a tribe’s future is a ‘dual dance’

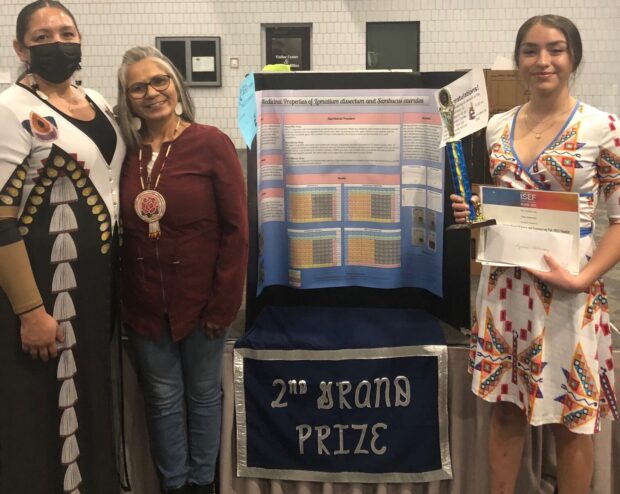

Walking through the halls of Lapwai Middle/High School, Principal D’Lisa Penney greets students by name and asks how their game went or how their family is doing.

One child runs up and gives her a hug.

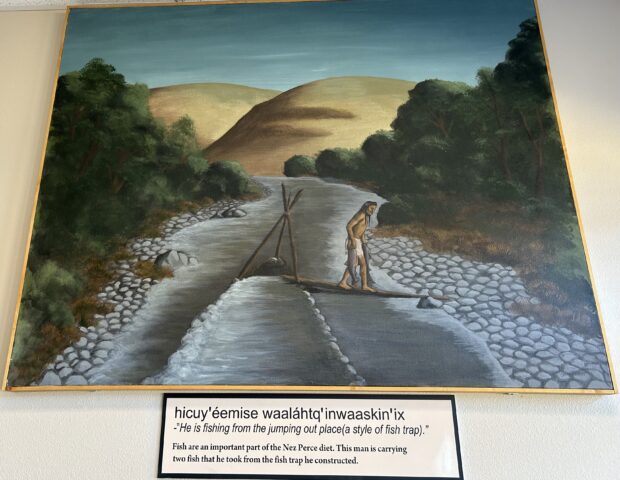

There’s a sense of community in the school, where hallways are lined with Nez Perce murals, words, and phrases.

But it’s taken work to foster that welcoming environment.

“We have a huge group of people who are impacted with that transgenerational historical trauma,” said Penney, who is a Nez Perce tribal member but did not attend school in Lapwai. “Even with me looking how I look, I struggle sometimes with that relation of trust because of that history.”

And “that history” means, in part, boarding schools — and the family separation, language loss, and assimilation that came with them.

Mistreatment that started in classrooms still impacts students and families, so rebuilding trust with them is essential.

“How we approach learning, and how we communicate with our families, and how we respond to a lot of things that wouldn’t be an issue in other schools is critical,” Penney said. “As is that mindset and that background and that lived experience of having people of color and people of the culture in the building.”

And Penney takes her role seriously; Lapwai schools educate the majority of the Nez Perce tribe’s future generation: “We are the helm. We are the heart.”

It’s a careful balancing act between grappling with the past and looking toward the future.

“It’s a dual kind of dance; we can’t ever let go of the historical facts that impact education,” Penney said. “Yet, there is an immense amount of responsibility and trust that are given to us, which is beautiful.”

Like Manning John, Penney followed her parents’ footsteps into education; her mother and father were both teachers. In that way, she feels lucky.

“I don’t know what it’s like to not have Native educators in my life,” she said.

And now, she’s ensuring that the students at her school won’t know that feeling either.

On the Fort Hall Reservation, Matt Wilson went from being a high school dropout to a high school principal

Matt Wilson’s Kiowa name is “Taw-Heen,” meaning Herd Bull or “one that takes care of others.”

The name fits.

Over the years, he has built relationships with Native American students in a number of ways: by starting and running the Fort Hall Legends Wrestling Club; by working as Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr. High School’s guidance counselor and dean of students; and by emceeing community events and basketball/football games “across Indian country.”

Now, as an administrator at Shoshone-Bannock High, his students remind him every day that he’s not a “typical” principal.

Wilson’s son, Keen Wilson, attends the high school and said his dad has a unique approach: “Anytime that anyone gets in trouble, he relates to them on that level — he understands what they’re going through,” Keen said.

It’s because Wilson’s been in their place.

“This is the reason I got into the education field, to help young Native youth understand that they are cared for and belong.” — Matt Wilson, Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr. High School principal

“During my years in high school, I spent more time trying to get out of school than I did in the actual classrooms,” he wrote in an email to EdNews. “I absolutely dreaded going to high school and eventually dropped out.”

He didn’t feel wanted or needed in that school. And that was on top of childhood adversity he faced, like homelessness and abuse.

But one school changed his mind about education: Haskell Indian Nations University.

It’s a small college with a predominantly Native American faculty and staff that serves about 1,000 students, all of whom are tribal members. There, for the first time, Wilson felt like he belonged and had potential. It inspired him to create that kind of school for others.

“This is the reason I got into the education field, to help young Native youth understand that they are cared for and belong,” he said.

Recently, Wilson and his son emceed a powwow held at a Pocatello elementary school. They introduced speakers and let out whoops of appreciation after each dance, stoking the crowd’s enthusiasm.

“We’re just spreading awareness that Native folks are still here,” Wilson said of the powwow. “We’re still thriving. We’re still doing all of our traditional doings and holding on the best we can.”

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.

This story is part of a series that was made possible with a generous grant from the Education Writers Association.