EDITOR’S NOTE: Eleven Idaho schools are launching on an experiment this fall. They are using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools. This is the third of a series of stories on the grant recipients.

Parma Middle School is, well, somewhere in the middle.

And it has been for some time, as the state’s latest five-star school ratings confirmed. The district’s Maxine Johnson Elementary School received three stars. Parma High School was a five-star school. But Parma Middle School received only two stars.

Even before the ratings were released in August, officials sensed something was missing in the middle school. They searched for an explanation for the nagging academic struggles that seemed unique to the middle school and its 335 fifth- through eighth-graders.

School officials concluded that technology was that missing element. And in a state grant application, school officials were brutally candid about the school’s demographic and social challenges — and about academic improvements that have proven elusive. The state responded with an $83,567.59 grant.

Changing the ‘changelings’

All of this makes the Parma pilot unique among the 11 projects under way statewide. While many of the grant recipients are high-achieving schools, Parma is the lone two-star school to receive a share of the $3 million — hotly contested money sought by 81 schools statewide.

Also unique is Parma’s grant application, which offers an unflinching look inside the rural Canyon County school.

Parma officials point out that the school is in its eighth year of trying to meet Adequate Yearly Progress, the accountability benchmark established by the federal No Child Left Behind law.

The application also talks bluntly about the myriad social issues standing in the Parma’s path, including rural isolation, high poverty, migrancy and high mobility rates, families broken by crime and incerceration, and a high number of English language learners.

But the same application speaks in compassionate terms about the challenges facing fifth- through eighth-graders. “The inherent nature of the pre- and neo- adolescent is that of a changeling, fired by growth spurts, hormonal surges, a burgeoning sense of autonomy and a lingering attachment to dependency.”

And the application makes another point clear. In order to bring systemic improvements to Parma’s schools, the district has made a strategic decision to change the educational experience for its changlings.

“The elementary and high school that make up the other parts of this three-school district have agreed that the logical site upon which to focus the resources of the pilot is the middle school, where students are most apt to ‘flounder’ in that critical time and age category where interest can flag, home support can waver, extraneous influences can prevail, and self-realization can falter.”

How it will work

Like many of the pilot grant recipients, Parma is gradually ramping up its high-tech initiative.

The front end work is still in progress: installing 17 new Ethernet “switches” that will cost more than $30,000, the largest line item in the Parma tech grant. Think of the switches like an airline’s “hub” airport. The school’s computer lines run through the switches. The more efficient the switches, the faster the computer system works.

It’s unglamorous work, but necessary to replicate the faster online experience of a home WiFi system. And Principal Peggy Sharkey knows what happens when middle school students are expected to slog through a slow classroom computer experience.

“They’re gone,” she said. “They’re visiting with their neighbors, they’re dinking around.”

When the new switches are installed, the heart of the project will follow.

Parma will deploy about 25 tablets, sufficient for an entire class to use at a time. This will free up room in the school’s existing computer labs and, say district officials, put the school on the leading edge of the technological movement. “This is just the beginning of the tablet thing,” said Jeff Baroli, the district’s technology coordinator.

The school will also buy a pair of Promethean ActivTables — interactive touch tables that allow students to collaborate on work in small groups, and allow teachers to track what each student is contributing to the group project. Those tables should be up and running by January.

The main goal is to focus on math and science, using interactive digital content in both subject areas. In a school where more than 70 percent of students qualify for free and reduced lunch, math scores for economically disadvantaged students continue to fall below state targets.

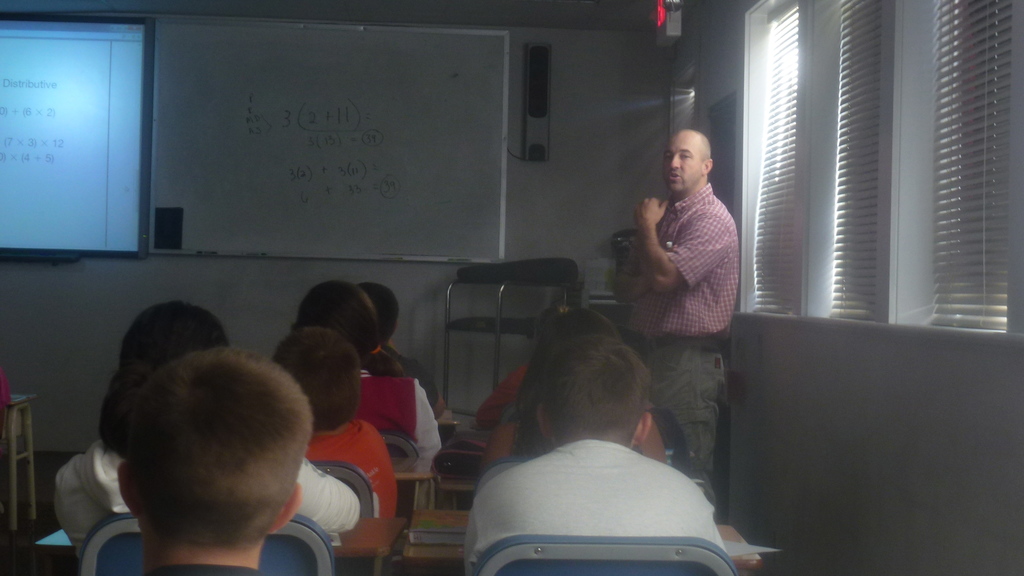

The digital math content is valuable for all students, Sharkey said, since it allows teachers to hone in on an individual student’s strengths or weaknesses. And with or without tablets, sixth-grade math teacher Kevin Sitts is already using the digital content; the emphasis on word problems makes the material a good match to the new Idaho Core Standards

And even though the focus is in math and science, the school hopes the technology will bridge gaps for its English language learners, which make up about 12 percent of the student population. The Promethean desks are part of that puzzle, Superintendent Jim Norton said, because they will allow students to write and work on digital English flashcards.

More stories about the 11 Idaho schools using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools: Learn about Kuna Middle School’s Chromebooks project. Learn about Middleton High School’s laptop pilot.