The reality rankles the fiscal conservative in Gov. Brad Little.

If half of the state budget goes into K-12, Little often says, then third-graders should know how to read. Little’s top education priority springs from that simple frustration.

“You can’t do everything, but that’s one thing you can really do, and that’s move the needle on literacy,” the first-year governor said in a recent interview.

But moving the needle is tough.

And teaching kids to read is difficult.

If Idaho really wants its young children reading at grade level — and prepared for fourth grade and beyond — that will take time. And money. The $26 million the state is spending this year on literacy programs is an increment in a multiyear effort.

That too is the reality.

Fall 2019: a reality check

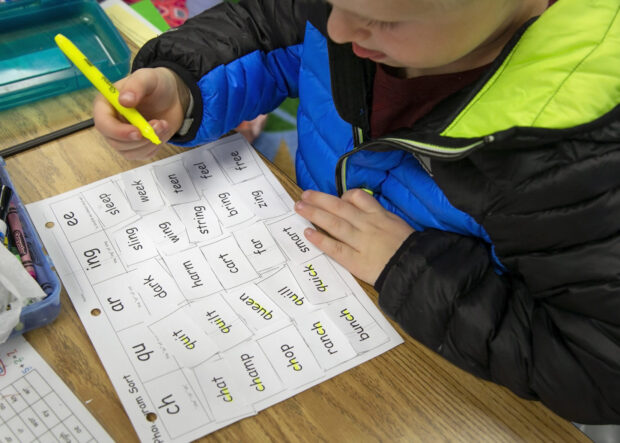

Each fall, about 90,000 kindergarten through third-grade students take the Idaho Reading Indicator, the state’s boilerplate screener for reading skills. The test measures whether young students have the reading skills — or, in the case of kindergartners, the pre-reading skills — that they should have at the start of the school year.

This fall’s results set a sobering baseline. Only 42 percent of kindergartners and 49 percent of first-graders were proficient. Second- and third-grade scores were better: 63 percent and 64 percent, respectively.

State superintendent Sherri Ybarra sees some good news in the numbers: The scores in first through third grades improved by 3 to 6 percentage points from the preceding fall. But State Board of Education member Linda Clark, a former West Ada School District superintendent, was alarmed by the kindergarten scores, down 3 percentage points from a year ago. “That means those kids spend 13 years of their school life trying to catch up.”

And beyond.

If students leave school struggling to read, more struggles await them.

“They can’t drive a car, they can’t buy groceries, they can’t pay the rent,” said Crystal Rosen, a kindergarten teacher in Cascade.

Thumbnails

Statewide scores are telling. But they tell only so much.

Scores vary widely from school to school, community to community, even within a few miles in the Treasure Valley.

Thumbnails from the 2018-19 school year tell a story of success interspersed with stagnation:

- In West Ada, Idaho’s largest school district, 80 percent of K-3 students read at grade level this spring. On the state’s required IRI tests, in fall and spring, West Ada scores improved by only 12 percentage points from fall to spring, compared to 17 percentage points statewide, But West Ada posted its biggest improvements in kindergarten and first grade. That wasn’t a coincidence. The district’s reading interventionists spend most of their time working with the youngest at-risk readers. “We can’t defend not focusing on K-1,” Superintendent Mary Ann Ranells said.

- In the Boise School District — a high performer on many other statewide metrics, such as college entrance exams and college go-on rates — only 66 percent of students finished the school year at grade level, falling below the state average. From fall to spring, after a full school year, kindergarten scores dropped in at least 14 elementary schools. “We know we’ve got some work to do with the literacy goals,” said Stacey Roth, Boise’s administrator of student programs. Some good news: This fall’s scores are up from the preceding fall.

- Only 51 percent of Caldwell School District students finished the year at grade level, lagging behind other large districts across the state. Caldwell faces many familiar demographic challenges that affect student achievement, and not just on the IRI. Caldwell has one of the highest student poverty rates in Idaho, and more than 60 percent of its students are Hispanic.

- Only a few miles away, the rural Notus School District is another high-poverty district, and more than a fourth of its student population is Hispanic. Yet Notus posted robust IRI improvements, as 78 percent of its students finished the year at grade level.

- Nearly 80 percent of students at Boise’s Sage International School finished the year at grade level. But scores at the relatively affluent Southeast Boise charter school were virtually unchanged from the fall. Teacher interventions helped some struggling students catch up, executive director Keith Donahue said, but nearly as many students lost ground and ended the year below grade level.

- Scores were also stagnant at Garden City’s fledgling and diverse Future Public School. Half of the charter school’s K-3 students ended the year reading at grade level. School leaders spent much of that first year simply getting a new school off the ground, co-founder Amanda Cox said, and are better prepared to focus on academics in year two.

A long history

If it feels like we’ve been here before, we have.

Idaho’s literacy initiative dates back to 1999, and Dirk Kempthorne’s first year as governor. One legacy from Kempthorne’s initiative was the IRI. The screener has been a part of the state’s testing battery, in one form or another, for the past two decades.

A reboot began to take shape in 2013, when then-Gov. Butch Otter convened a task force to revamp Idaho’s K-12 system. Among its eclectic menu of 20 recommendations: All students must master literacy in the early grades. “Reading proficiency is a major benchmark in a student’s education,” the task force said in its final report. “Students must learn to read before they can read to learn content in other subject areas.”

In 2016, Otter and lawmakers agreed on a new literacy law with lofty ambitions: “It is the ultimate goal of the Legislature that every student read at or above grade level by the end of grade 3.”

They backed up the rhetoric with more than $11 million — a $9 million budget increase. They also agreed to divvy up the money based on reading scores. School districts and charter schools with higher numbers of at-risk readers would receive a larger share. (That also means schools receive a smaller slice of the pie if their scores improve.) State leaders also agreed to replace the existing IRI.

Little’s plan isn’t a new initiative as much as it’s an extension of Otter’s. It has more money behind it: that $26 million line item lawmakers approved this year. The new online IRI — which promises teachers more student data, more quickly — launched during the end of Otter’s third and final term in office.

The hope is that the dedicated funding, and the wealth of data, will fix a problem decades in the making.

“We didn’t know what we didn’t know 20 years ago,” said Ybarra, who was teaching third grade when Kempthorne launched his reading plan.

Obstacles and objectives

Ask educators, parents and politicians about the obstacles — the things that keep kids from learning to read — and a few common themes emerge.

The state’s $26 million allows local schools to decide how to provide at-risk readers with 30 to 60 hours of extra help this school year, but educators say there’s never too much money or too much time. “Reading doesn’t happen overnight. Literacy doesn’t happen overnight,” said Kali Webb, Sage International’s elementary director.

Parents and educators also see a disconnect — even engaged parents might not know how to prepare their preschoolers, or reinforce what their kids learn in school. “Some parents do this very well,” Caldwell Superintendent Shalene French said, “(but) not every parent can be their child’s teacher.”

Doni Davis, in her 13th year as principal at West Ada’s Chaparral Elementary School, sees a basic change in the students. Some of her new kindergartners come from unstable homes — but some are simply unprepared, more adept at using devices than learning to read. “They come to school with less and less vocabulary every year.”

Despite these many obstacles, Little remains resolute. The goal is 100 percent proficiency, without exceptions or excuses.

“Anything less than that, we haven’t done our job,” said State Board of Education President Debbie Critchfield, who co-chaired Little’s K-12 task force this year, which focused on college and career readiness and early literacy.

But 100 percent is a tough objective.

No school district or charter hit 100 percent this spring. Or this fall.

No school district even hit 90 percent this spring. Or this fall.

Five charter schools reached the 90 percent plateau this spring. Only one, Meridian’s Compass Public Charter School, reached 90 percent proficiency this fall.

These are also realities.

Idaho’s reading challenge: This series at a glance

Day One

Reading realities: Idaho plays catchup

Following the dollars, defining success

Day Two

What’s working? School success stories

Idaho’s daunting demographic hurdles

Day Three

Testing kids, and seeking answers

Early education expands across Idaho

Day Four

Reading policy and reading politics