TWIN FALLS — Some anecdotes are harrowing.

A few years ago, refugee students were encouraged to take part in a quilting project, creating a square depicting their home country. Aiham Taliv, a refugee from Iraq, prepared an illustration of his village — while, overhead, a helicopter opened fire. The quilt, including Taliv’s illustration, went on public display.

“We’re wanting (the community) to understand what their kids’ lives were like. … But it’s also a healing process for these kids,” said Bill Brulotte, the local school district’s federal programs director.

“We’re wanting (the community) to understand what their kids’ lives were like. … But it’s also a healing process for these kids,” said Bill Brulotte, the local school district’s federal programs director.

Other anecdotes are whimsical. Such as the story about a student at a school birthday party, who wasn’t sure how to peel the paper off a cupcake. Or the story about a student, seeing a classroom with electricity for the first time, who just kept flicking the classroom light on and off, “just because it was pretty cool and exciting,” said Khrista Buschhorn, an instructional coach who works with English language learners.

These transitions — from the heartwrenching to the lighthearted — have become commonplace in Twin Falls. For three decades, a city in the heart of farm and dairy country has become an unlikely destination for refugees. Teachers and administrators have grown accustomed to assimilating newcomers into their schools. In April, residents resoundingly rejected a petition drive challenging the refugee program.

A symbiotic relationship

Thirty-one years ago — and almost two decades before he would become the Twin Falls School District’s superintendent — Wiley Dobbs landed his first job in the Twin Falls schools. He taught junior high school world geography, just as Twin Falls’ College of Southern Idaho opened its Refugee Center. At this time, most of the refugees came from Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia.

Dobbs quickly discovered he could learn from the refugees. When his geography class turned its attention to Southeast Asia, he said, “I had go-to people.” One of Dobbs’ students taught him to say hello and goodbye in Laotian. In turn, Dobbs learned to pronounce the names of his refugee students, instead of simply addressing them by their first initial.

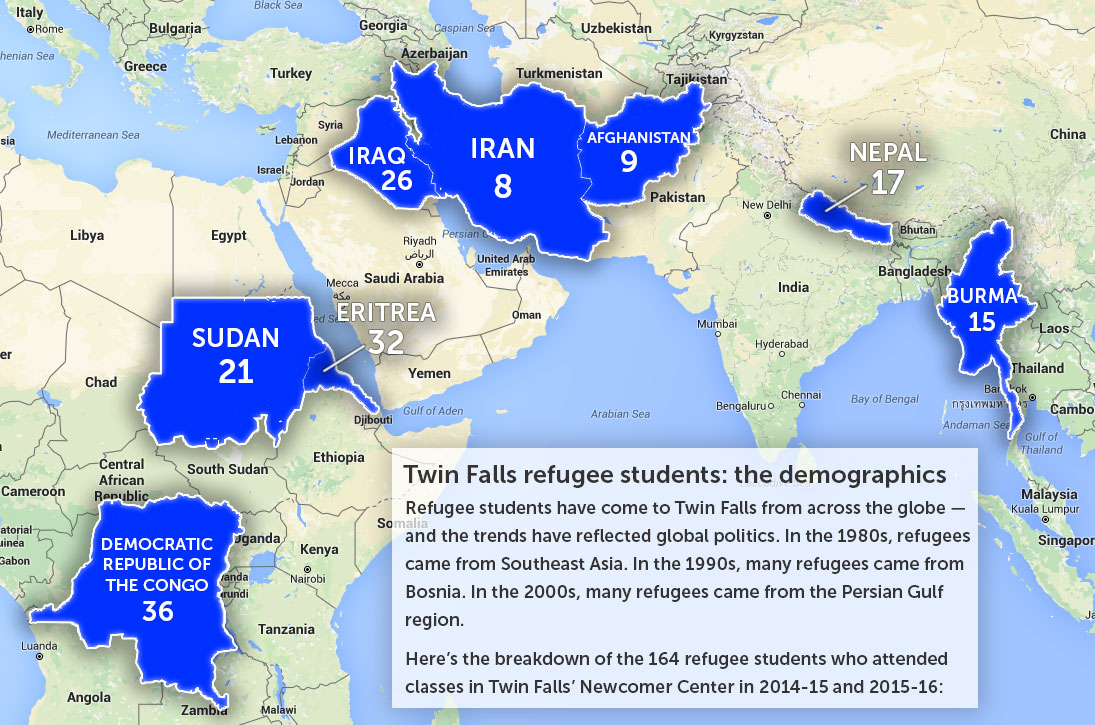

Over the years, Twin Falls’ refugee population patterns mirrored global events. In the 1990s, many of the refugees came from Bosnia. In the 2000s, many refugees came from the Persian Gulf region. Many of today’s refugees come from Africa, Iraq, Afghanistan and Nepal.

The relationship has been symbiotic — and Dobbs has found his hometown to be receptive. “It’s expanded our world here in little Twin Falls, Idaho.”

But as an educator, Dobbs sensed something could be done better.

‘Wherever they are at is where we start from’

For the students who fled Southeast Asia three decades ago, there was no transition from the school experience of their past to the new school environment that awaited them in south-central Idaho.

“We just plunked them in the classrooms,” Dobbs said.

When Dobbs became superintendent in 2003, district leaders agreed to try something different.

That’s where the Newcomer Centers comes in.

The centers are designed to provide an open-ended transition for refugee students. Some are already accustomed to the structure of school, and some have English skills. They might stay in the Newcomer Center for only a couple of weeks. Other refugees stay in the center for seven or eight months.

“Wherever they are at is where we start from,” said Rhonda Slagel-Sao, the teacher at Lincoln Elementary School’s Newcomer Center.

The district has only a short time to figure out that starting point. District officials get about two weeks’ notice before refugees arrive in school. They get word from the College of Southern Idaho, which in turn is notified by the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. Within that narrow window, they set up a meeting with the student and his or her family — to learn about the student’s background and language skills, and try to develop a level of trust between the school and the newcomers.

“That first meeting is really important,” said Lodie Steen, a family liaison for the district.

Once in Slagel-Sao’s class, elementary students spend the morning learning about the calendar and weather, and other topics designed to ease them into a new culture. Some time in the afternoon is set aside for group work in math. English is a matter of constant immersion.

“They learn enough survival English pretty quickly, said Slagel-Sao, “because they have to interact with me all day.”

Building bridges, an inch at a time

The turnover is constant. One Friday in February is the first day of school for five students, newcomers among newcomers. It is also the last day for four refugee students, who are moving to Boise.

Another constant is teaching the essentials, in ways that transcend language barriers. Niyibizi — one of Slagel-Sao’s first-day students, from the Democratic Republic of the Congo — receives a gentle reminder about pushing his chair under his desk before recess. Blending basic English with broad gestures, Slagel-Sao tells her students what they should do in case of a fire.

After the fire drill, Slagel-Sao wraps up the week with a going-away party for students leaving Twin Falls. Slagel-Sao goes online to find music for the party. The class settles on a YouTube clip of “Let It Go” from the Disney film “Frozen.”

For Keren, a second-grader from the Congo, her first day ends early, and just as the party begins. She is escorted home with a headache and fever, a reaction to a vaccination from the previous day. Illnesses are not uncommon for newcomer students, say school officials; it’s an outgrowth of the overwhelming transition to a new country and a new school.

The wife of an immigrant from Cambodia, Slagel-Sao understands the long journey ahead for her students.

“I cannot focus on that,” she said. “The bridge has to be built an inch at a time.”

The process of assimilation

For Elsa Tekle, an 11th grader who has been in Twin Falls for 11 months, the stay in the Newcomer Center was short.

Most classes in her native Sudan were taught in English. Going over basic math and the alphabet was easy, she said. After two months, the district moved her from the Newcomer Center to Canyon Ridge High School.

The transition had its scary moments. She wasn’t accustomed to moving from classroom to classroom, but she said her new classmates were helpful. Even now, she likes to spend downtime talking to fellow refugee students in her native and more comfortable Arabic.

At Canyon Ridge, a new high school that sits on the edge of the growing north side of Twin Falls, newcomers are integrated into regular classrooms. About 100 of the 1,200 students are English language learners — and Canyon Ridge prefers to assign groups of ELL students to a regular class. That way, newcomers aren’t isolated. On the other hand, that means they tend to hang out together.

“It’s a process,” said Kimberly Allen, an instructional coach at Canyon Ridge.

The assimilation culminates each year with International Week. Newcomers are encouraged to wear their native dress and bring food from their native lands. They have the chance to play in an annual student-faculty soccer match. The faculty usually loses badly, says Dobbs. During the talent show, the refugee students often surprise their classmates with their musical or dance skills. “They just blossom with the opportunity,” said Allen.

And for the refugee students, the transition to a new school in a new land is all about opportunity. They might come to Twin Falls years behind students their own age, but they also see a chance to leave behind the hardships of their childhood.

Tekle is already looking ahead. She plans to go to college and study nursing — a good job that would also allow her to help people. “I have a chance to be what I want,” she said.

A community’s decision

For local critics who wanted to shut down the College of Southern Idaho’s Refugee Center, April 4 was deadline day. They needed to collect 3,842 signatures to place a referendum on the county ballot. They collected only 894.

To Twin Falls Mayor Shawn Barigar, the results demonstrated that the petition drive was headed by a “very small but vocal and visible minority.” In rejecting the effort, voters and business leaders affirmed their support of diversity — in their communities and classrooms.

“It’s something that companies are looking for,” said Barigar, who doubles as president and CEO of Twin Falls’ Chamber of Commerce. “It may not be super high on the list, but it’s something they expect from a community.”

Dobbs tried to be diplomatic during the petition drive. He said district employees would deal with the outcome, whatever it turned out to be. He also made his preferences clear.

“We’ve developed quite an affection for our refugee kids,” he said during a February interview.

The outcome validated what Dobbs had said all along about his hometown and its home-grown refugee program.

Many residents say they want to be sure the federal government and local officials have an extensive refugee vetting process in place. But many of these same residents also see what refugees contribute to a community and to a classroom. After three decades of helping refugees make the transition to a new home, Twin Falls residents wanted to see their community continue to serve this role.

Shutting down the Refugee Center would have effectively ended Twin Falls’ refugee education program. When the community rejected that notion, Dobbs didn’t seem surprised.

“I think there’s a great deal of support for the refugee program here in Twin Falls.”

This series at a glance

Day One: Refugee programs become embroiled in a national debate

Day One: In Boise’s Bridge Programs, immigrants learn to be students

Day Two: Twin Falls reaffirms support for refugee program