Pangaea Finn left clues she was gifted as early as age 2.

As Sean Finn remembers it, the first clue came over dinner. He and wife Elizabeth were eating Chinese, discussing whether Pangaea could actually read the books they flipped through every night, or if she just had them memorized. He cracked open a fortune cookie and handed his 2-year-old daughter the paper inside.

She read the fortune aloud to them, ending any debate.

The next year, Pangaea’s preschool teacher told her parents that the 3-year-old was winning every round of Hi-Ho Cherry-O the kids would play at school. Unlike the other kids, Pangaea could add, her teacher suspected, and she was rigging the counting game in her favor.

At the teachers suggestion, Sean and Elizabeth had Pangaea’s IQ tested. Sean, a conservation biologist, and Elizabeth, a therapist, weren’t expecting the results: Pangaea was profoundly gifted.

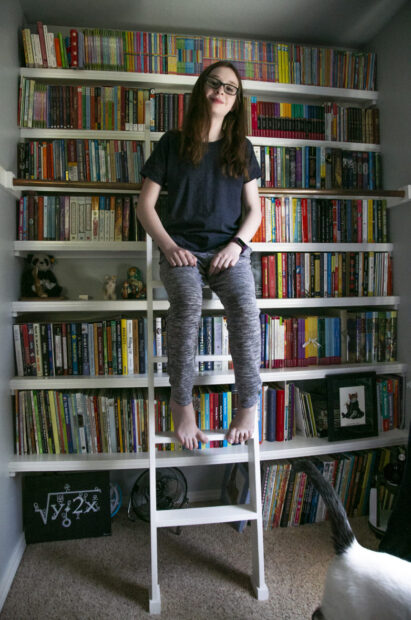

Today, at age 14, Pangaea Finn is a novelist, an accomplished pianist and viola player, a nationally-recognized young conservationist and a Boise State Bronco.

She started her first year as a full-time undergrad last week.

“I’m not worried about it,” Pangaea said, calm and collected about starting Freshman year. “I think it’s a lot of fun going to college.”

Pangaea’s education has been anything but conventional, driven by her endless appetite for knowledge and shaped by a piece of advice her parents received early on: try to keep her challenged.

“One thing that happens with gifted kids, if they’re not being fed enough information, they get bored,” Elizabeth said.

Challenging Pangaea has taken a patchwork of public schools and online courses, AP tests, summer camps and a college-level lecture series she sometimes watches for fun.

Pangaea spent a few years each in the Highly Gifted program at Boise’s Collister Elementary School, and a few more at Boise’s Treasure Valley Math and Science Center. In between, she took classes online and enrolled in courses like Quantum Physics and Calculus 3 at Boise State.

Piecing it all together has been like navigating a puzzle blindfolded, Elizabeth said.

The family found help — and solidarity — in the Davidson Institute, a Nevada-based organization for the profoundly gifted.

Like other families they’ve met through Davidson, Pangaea’s parents have learned to think ten steps ahead, trying to map out options for Pangaea to advance at her lightning pace.

“It’s like somebody who is starving intellectually, and they can’t stop feeding themselves,” Elizabeth said. “You have to keep stocking the intellectual refrigerator, so to speak.”

As a therapist, Elizabeth has started consulting with parents of gifted children, trying to help them navigate a unique dynamic which she feels is sometimes misunderstood.

“It’s important that people know these individuals exist, and even though a lot of times parents are seen as pushing them, I wish people would take a step back and re-evelaute that,” she said. “A lot of us in this situation are just trying to provide our kids what they hunger for. What they need. It’s not a push, we’re giving them a platform.”

Pangaea doesn’t technically have a high school diploma, but she’s entering Boise State with as many college credits as most college juniors. She took college entrance tests at age 11, and scored in the 99th percentile on both the SAT and ACT.

A spokesman from Boise State says Pangaea is one of eight students 16 or younger enrolled as full-time undergraduates.

“In my 25 years experience in academia, I have never met anybody like her,” said Daniel Fologea, an assistant professor who runs a research lab at Boise State.

Pangaea started volunteering in Fologea’s biophysics lab last year, and is now running her own experiments independently, he said. She also helps host a science outreach program in schools and libraries and Fologea said she will be a co-author on an upcoming manuscript.

“She is a great ambassador for this younger generation, to really motivate them,” he said.

Pangaea is pursuing a triple major in math, physics and piano performance at Boise State — but her interests don’t end there.

She volunteers for the Boise Philharmonic and plays both piano and viola. Her music room at home is lined with trophies and she played with the Meridian symphony earlier this year.

She’s written multiple novels — mostly sci-fi — one of which earned her a Scholastic Art and Writing Award this year.

And in August, Pangaea was nationally recognized for her conservation work by the North American Association for Environmental Education. She runs a nonprofit called the Orangutan Gang, which raises awareness about rainforest deforestation due to palm oil cultivation, and the toll that takes on the habitat of endangered orangutans.

The project was inspired by the work of another teen she met through the Davidson Institute, who first taught Pangaea about “the palm oil issue.” In 2013, Pangaea put together a website to teach people about palm oil harvest and encourage supporters to live palm-oil free. She’s contacted zoos about whether they use palm oil products, and hosted a number of informational sessions at Zoo Boise.

Pangaea has never seen an orangutan in its native habitat, or visited the rainforest in Borneo — a dream of hers. In the meantime, she sells reusable grocery bags and orangutan sewing kits to raise money for orangutans through the Orangutan Foundation International.

“I really think that I can actually make a difference and help save the rainforest,” she said. “Just raising support and helping discourage palm oil use.”

If she’s not practicing piano or viola, working on homework or turning the pages on one of the handful of books she reads each week, Pangaea might be watching Sherlock with her friends, playing Settlers of Catan with her parents or working on crafts.

Whatever Pangaea starts, she finishes, Sean Finn said.

This summer, Sean said, Pangaea wanted to make a cape for a Hermione costume. Despite having limited sewing experience, she purchased a pattern, fabric, and taught herself to sew the cape with a machine.

“Nobody sat down and had to teach her, or had to convince her to continue. It was all on her,” Sean said. “That kind of passion and commitment is something I find really rewarding as a parent.”

When Boise State Professor Shari Ultman first learned Pangaea would be enrolling in her Calculus 3 course as a 13-year-old, Ultman wondered how the other college students would react.

Ultman sometimes teaches high-school students. But never before had she instructed a 13-year-old, visibly younger than the other students.

It ended up being a non-issue. In fact, Ultman said, Pangaea brought the class closer together.

“She’s outgoing and she’s personable,” Ultman said. “Just a very joyful spirit to have in the room.”

As a professor, Ultman said, working with students is always a humbling experience.

Working with Pangaea went beyond that.

“I have had a lot of extremely, extremely intelligent, gifted, hard-working students. But Gigi (Pangaea) is really a very rare student,” she said. “…Gigi has the potential to succeed at the highest levels of whatever fields she chooses to pursue.”