For years, Idaho state superintendent Sherri Ybarra and other state leaders have advocated the need for social-emotional learning in Idaho schools. It emerged as a core theme in the governor’s 2019 “Our Kids, Idaho’s Future” task force. In 2020, Ybarra went toe-to-toe with House Republicans over $1 million to train teachers on social emotional learning — teaching students the positive attitudes and behaviors that can help them succeed in the classroom, and in life.

Now, the State Department of Education is distancing itself from the term “social-emotional learning,” which has been drawn into the fierce, divisive debate surrounding critical race theory.

“We are not distancing ourselves from the concept of SEL, and the important work of supporting students,” SDE spokeswoman Kris Rodine said. “But the term ‘social-emotional learning’ has recently been co-opted to become a point of controversy, and interpreted to mean something we do not advocate.”

The SDE will use different terminology, Rodine said, and be explicit about what it does advocate: supporting students’ mental and behavioral wellbeing.

The rhetorical shift is subtle, but it has created a pothole in the state’s new roadmap for improving the behavioral wellbeing of K-12 students and staff. The work plan finalized last month acts on only 10 of 11 recommendations the state was considering — it leaves out a recommendation to adopt a statewide framework for social-emotional learning, which was intended to help unite scattered efforts at the district level.

What is social-emotional learning?

Social-emotional learning (SEL) is a widely used academic term for teaching kids emotional and interpersonal skills, like respecting one another, setting goals and recognizing their emotions.

Schools in Idaho and across the country have increased their focus on SEL over the past few decades as they look to support child well-being holistically, not just academically. The idea is that teaching these skills to all students helps them manage emotional stress, better succeed in school, avoid risky behaviors, and find success in college and the job market after graduation.

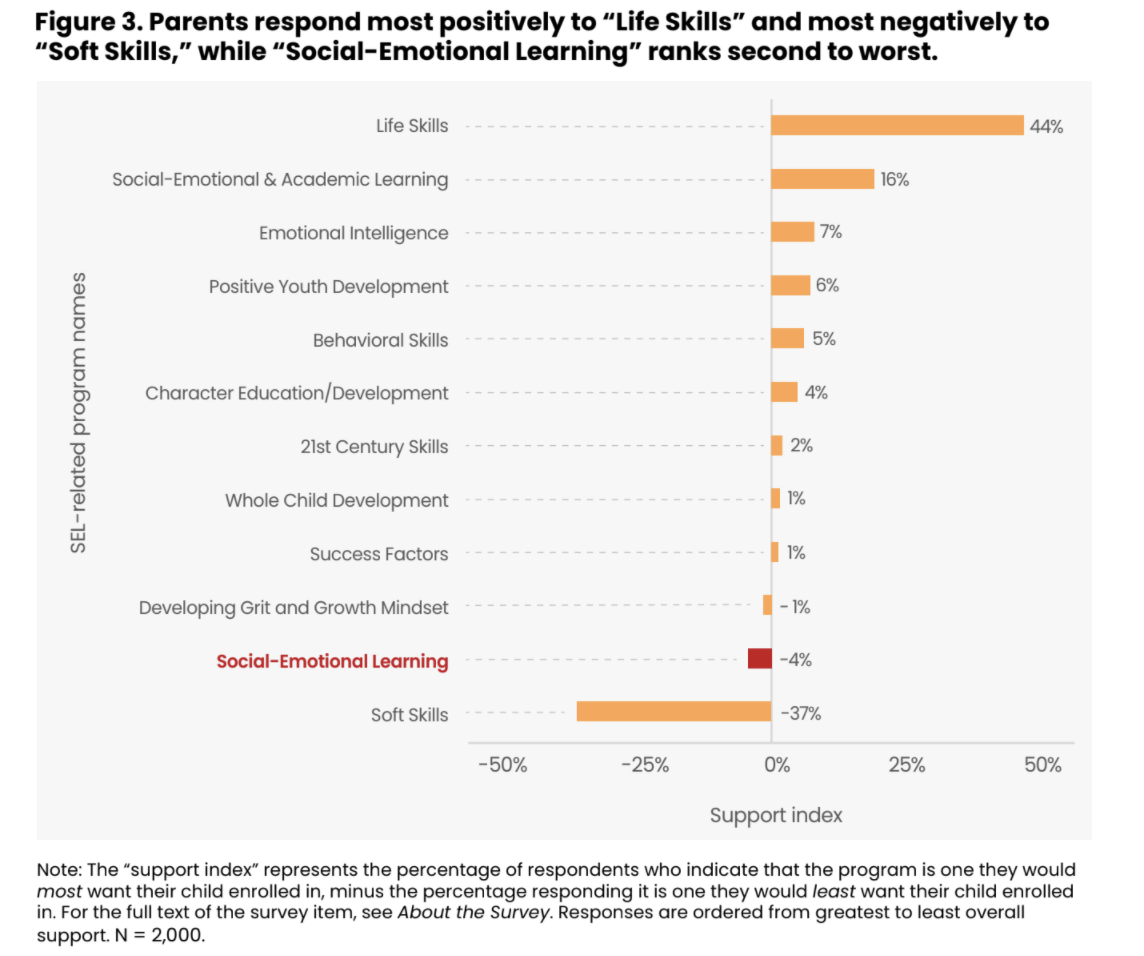

But the term social-emotional learning has taken on political baggage as conservative activists and politicians conflate it with fears about liberal “indoctrination” of youth at school. And a survey from the Thomas Fordham Institute indicates that the term is just not popular with parents.

The political furor has consequences.

School districts are catching heat from patrons about their efforts. And the statewide framework, left out of the roadmap, could have helped streamline districts’ approach to SEL, and led to future expectations for the social and emotional skills kids should be learning in Idaho schools.

State backs off from its SEL framework

The SDE convened a group of state mental health workers and educators this spring to analyze how Idaho could better address youth mental and behavioral wellbeing. One of the group’s 11 recommendations was adopting a statewide framework for SEL, through a group called CASEL (the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning).

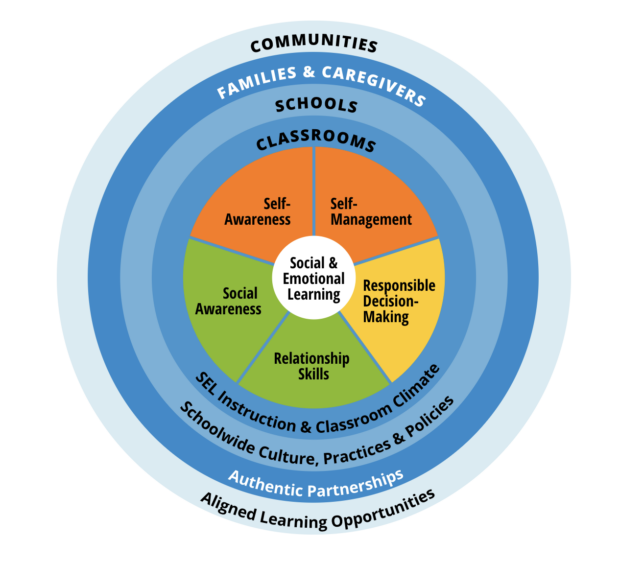

Eric Studebaker, the SDE’s director for student safety and engagement, wrote in a memo to Ybarra that adopting the CASEL framework didn’t tie the state to a learning program or any specific services. It was a way for Idaho educators to use common language around what SEL entails. By CASEL’s definition, that’s skills like self-awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision making.

“This type of framework decision seems foundational,” Studebaker’s memo said.

The framework was also a starting point for leaders to match SEL outcomes with Idaho’s existing college and workforce competencies, and potentially set statewide expectations that students learn social and emotional skills.

States like Nevada and North Dakota have adopted statewide expectations that teachers use SEL in the classroom, and some Idaho districts have already used CASEL to create grade-level standards. Currently, it’s up to Idaho districts to decide whether teachers incorporate SEL into classroom lessons.

The SDE has decided not to adopt the CASEL framework. Not at the moment, anyway.

Studebaker said the department is avoiding the term “social-emotional learning.” He pointed to the Fordham poll.

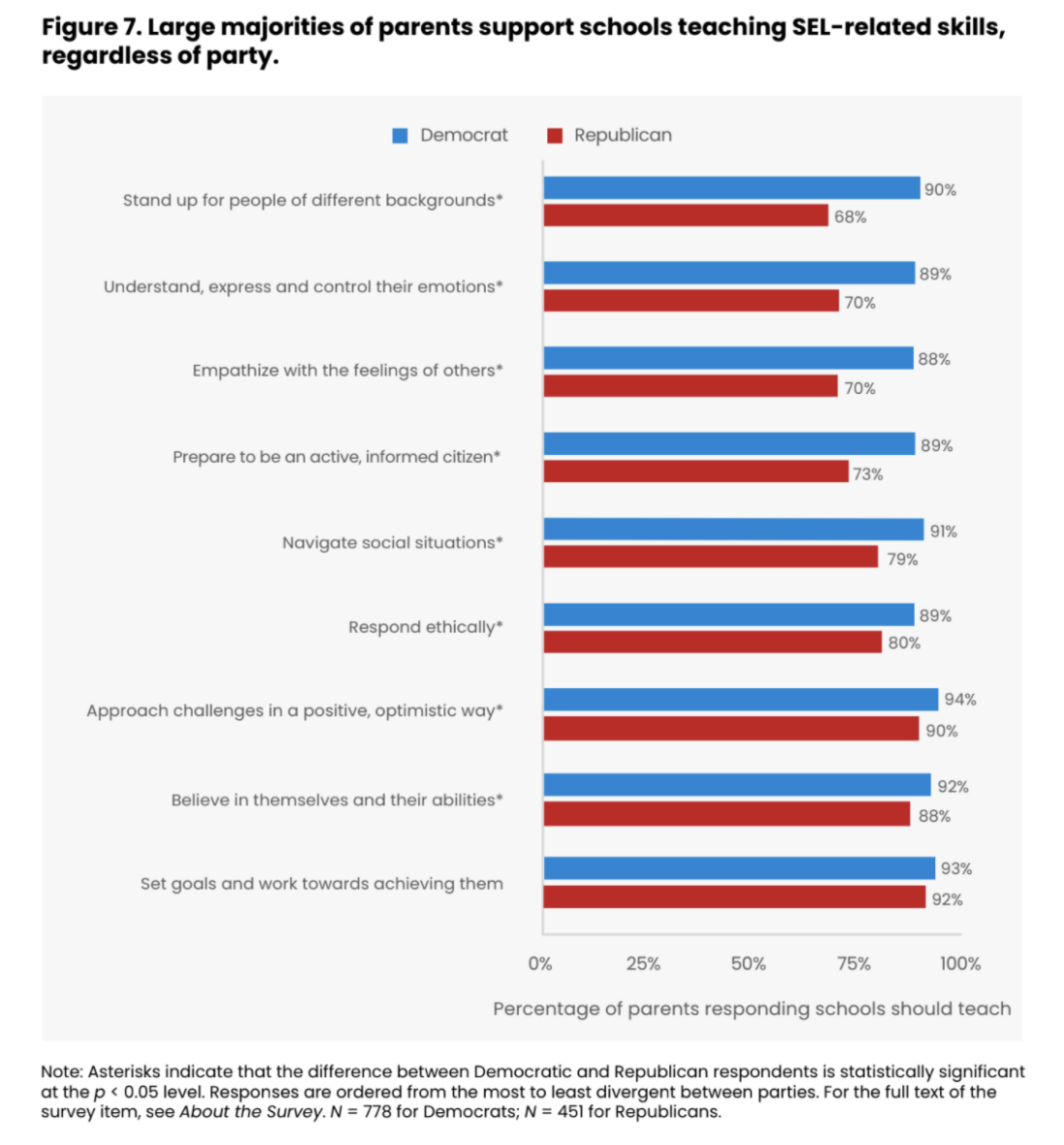

When Fordham asked 2,000 parents across the country if they’d enroll students in a social-emotional learning program, parents recoiled. However, the majority of parents from both political parties said they support teaching students core social-emotional skills:

Despite hesitancy over the term, the SDE still intends to support SEL components, Rodine said. That includes helping students develop skills they need to be successful, resolve conflicts and cope with adversity. The department also plans to help schools detect when students need help dealing with negative emotions and connect families with support services.

SEL pushback not new in Idaho, but growing

Anti-SEL rhetoric surfaced at the Idaho Statehouse during the 2020 session. During a House Education Committee meeting, Republican committee members suggested that teaching students social-emotional skills was akin to social control from a dystopian novel, and said interpersonal skills should be taught by parents.

“It seems like everything is flipping. Now we’re going to deal with things that should be dealt with in the home and then the home is going to try to teach math,” Idaho Falls Rep. Barbara Ehardt said.

That criticism has taken off in a big way this year.

The Idaho Freedom Foundation argues that SEL is a “vehicle for critical race theory” in schools, and took specific aim at CASEL for suggesting that SEL can create more just and equitable schools. Some schools have leveraged aspects of SEL to “grapple with broader issues of social justice,” according to a report on the CASEL website.

IFF’s stance has been echoed by members of the public, who criticized SEL at summer meetings of Lt. Gov. Janice McGeachin’s education indoctrination task force and at local school board meetings.

For example, Nampa school board candidate Tracey Pearson voiced her criticism to both critical race theory and social-emotional learning at a recent candidate forum.

“I think CRT, SEL, which is social-emotional learning, diversity, equity: Those are all intertwined. They basically tell the children and young adults … that by the color of your skin, you’re either oppressed or the oppressor,” she said.

School districts say they’re sticking to SEL

Social-emotional learning is not anything new, says Keith Orchard, who is in charge of SEL efforts in the Coeur d’Alene School District.

Decades ago, schools taught SEL components as “character traits,” like how to share and be a good teammate, he said. Those kinds of lessons are still part of the Coeur d’Alene’s SEL curriculum, where teachers talk to kids about peer pressure, how to make safe choices and how to manage stress. Missing from the lessons, Orchard said, are any teachings that white people are bad or that all U.S. systems are inherently racist, the central concern of critical race theory critics.

“There are some who have associated SEL with other movements and ideas that worry them, believing that SEL is ‘code’ for critical race theory,” Orchard wrote in an email. “I think that if most people really saw what teachers are doing, they would feel very comfortable with the idea of SEL.”

Despite public concern over the term, Orchard said that Coeur d’Alene continues to grow and develop the SEL focus in schools.

The Nampa School District, where school board candidates are decrying SEL, will also stay the course, spokeswoman Kathleen Tuck said. Nampa has ramped up its focus on student mental health and well-being in recent years, and has adopted CASEL’s framework to create grade-level expectations for students’ social and emotional development.

The goal of teaching social and emotional skills is to help build students’ positive mental health, resilience, and ability to adapt to all types of situations, according to explainers on Nampa school websites.

“As a district, our focus is not on political agendas,” Tuck wrote.

“…If you talk with parents who have lost children due to violence or self-harm, if you talk with parents who have had children struggling with eating disorders or depression, you realize that today’s students need assistance more than ever before.”