* Reporter Sami Edge will focus on covering youth behavioral health services during the 2021 Legislative session. Do you have a question about the topic, or a story you’d like to share? Contact her at [email protected] or 775-225-8689.

A new survey of behavioral health services in K-12 schools reveals a scattered landscape of programs across Idaho, where access to services is influenced by where a student lives, and the effectiveness of programs is rarely formally evaluated.

The State Department of Education paid research organization Education Northwest just over $17,000 for the survey, in response to a legislative mandate handed down last year. Some 80 percent of district administrators replied to the survey, which asked about behavioral health services available to students prior to COVID-19 disruptions. Students and education leaders say the global pandemic has only increased the urgency of providing these supports for youth.

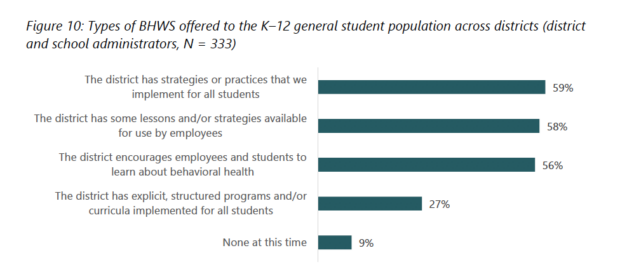

More than 90 percent of school leaders and administrators said that providing behavioral health services helps students feel safe, readies them to engage in learning, and supports stronger student/teacher relationships. But only 60 precent of districts have a strategy or practice to support all students, the survey found, and just 27 percent reported having a “‘structured program” for behavioral health services. School counseling services were the most common support, available at 57 percent of surveyed schools.

“What the data shows me is that our schools are very, very different in a variety of ways when it comes to behavioral health and wellness services, from those that are doing absolutely nothing to very robust, early adopters,” said Dr. Eric Studebaker, director of student safety and engagement for the State Department of Education.

The report also confirmed what Studebaker said were common assumptions when it comes to behavioral health access. Rural and charter schools reported offering fewer behavioral health services for students, families and employees. While non-rural districts say a lack of time and money are some of their biggest barriers to expanding behavioral health supports, rural districts also cite location as a major barrier.

The array of programs across the state are “most frequently assessed informally or not assessed at all,” the survey found. And districts that do offer behavioral health services report funding them largely without state funds or with a mix of state money and outside resources. Very little of the funding comes from state dollars allocated for mental health, the survey says.

“That is a challenge if we are seeking parity in services across LEA’s (Local Education Agencies),” Studebaker said. “Right now, whether or not these services exist is left up to the LEA.”

The SDE submitted the survey to Idaho legislators in January and Studebaker plans to present the findings to the State Board of Education at an upcoming meeting. He plans to convene groups of education stakeholders to talk about the survey during the spring, and to formulate behavioral health recommendations for State Superintendent Sherri Ybarra by July.

“I think we need to decide as a state: What’s our vision for behavioral health services in K-12 schools?” Studebaker said.

Read the full report below: