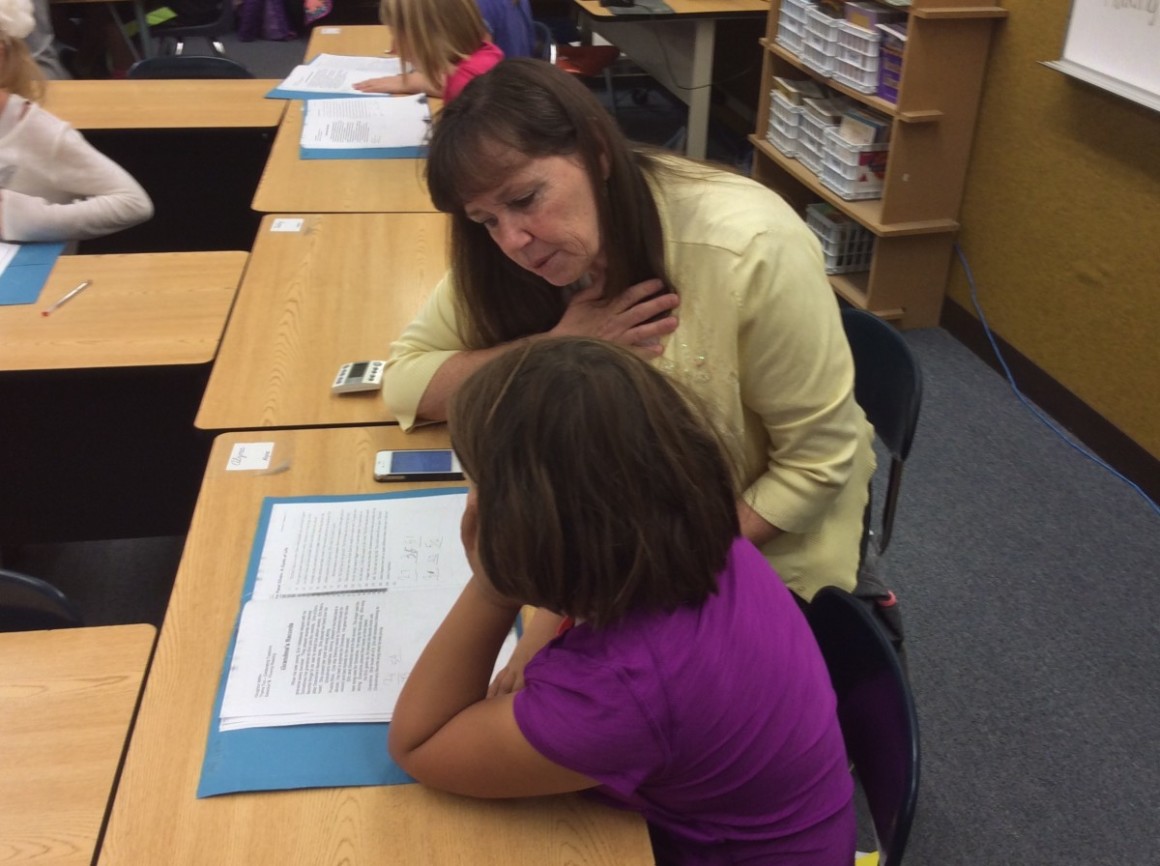

Shifting to a four-day teaching schedule was a big change for Chris Barnes.

Shifting to a four-day teaching schedule was a big change for Chris Barnes.

Like her students, the third-grade teacher at Preston’s Oakwood Elementary School had to get used to days that started earlier and ended later. But she also had to figure out how to best fill a classroom day that started at 8 a.m. and ended at 3:45 p.m.

Now, she sees the advantages to the new bell schedule. Barnes has the time for longer reading sessions, to help her students make the transition from learning to read to reading to learn. “Having that longer reading time, you can do more with it, I believe,” she said.

The most important question about Idaho’s four-day schools remains a mystery: Do the longer school days and the three-day weekends help or hinder learning? Yet there is no disputing the on-the-ground changes the four-day calendar has brought to Idaho classrooms. The schedule has transformed how teachers teach, who teaches in rural Idaho — and how students learn.

Rethinking the class day

The math behind a four-day calendar appears straightforward. For four days, teachers get more time with students, usually 45 minutes to an hour each day. Then, students and teachers alike get three days off.

For teachers — especially those who had to make the switch from the five-day routine — the move is anything but simple. Does it make sense to assign homework over the long weekend, or should students have the three days to catch up and recharge? Is it fair to give tests on Mondays? During the week, how much homework is too much? Is there a way to keep first-graders from fidgeting late in the day? Is there a way to keep high school students focused late in the day?

The key, says Glenda VanderWoude, a first-grade teacher at Notus Elementary School, is “putting more into each chunk of time.” The teaching part of the day has to be a little more intense, because kids will need more time and opportunities for review. Class segments have to be kept a little bit shorter, to allow more breaks.

In Preston, Barnes focuses on the basics first. Her 24 third-graders start out the morning with math and reading — the cornerstones of the new Idaho Core Standards.

In an adjoining building, at Preston’s Pioneer Elementary School, Lisa Wakley’s 22 first-graders get constant nourishment: breakfast at 8 a.m., lunch at 10:50 a.m., a snack at 2 p.m. “It’s more about the eating than the tiredness,” Wakley said.

She’s mindful that the days can be tiring, especially for kids who board a bus at 7 a.m. and get home at 5 p.m. She keeps homework to a minimum — 20 minutes a night — but says it’s needed to reinforce reading skills.

Across town, Preston High School math teacher Kimble Smith wrestles with the homework question as well. He still assigns homework, because he thinks students need the repetition. But he also sees more students squeezing in their assignments at the end of the class period, or before school.

Smith doesn’t like the four-day schedule. He thinks the days are too long even for high schoolers. As for Smith, he says he is in from 7 a.m. to 5:30 or 6 p.m., providing extra help for students. Then he comes in for a few hours on Friday or Saturday to grade papers or prepare lesson plans.

“I’ve never put in this much time before on other schedules,” said Smith, who is in his 10th year in Preston.

Making the most of the longer day

In Rathdrum, the North Idaho STEM Charter Academy has known only a four-day schedule. It was a conscious decision, unrelated to cost.

First- through 10th-graders are in from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., and it’s a tiring day, said co-founder and principal Scott Thomson. They get one shorter period, a 45-minute music or P.E. class. All other classes run 65 minutes, to accommodate the school’s project-based curriculum. “Jamming those into a 50-minute period is difficult,” he said.

At Preston High School, the 59-minute periods give Lynn Harris more time to teach cooking and sewing labs. She has no significant problems with a four-day schedule, which she thinks is misunderstood. “I think there’s an assumption that if you’re not here five days a week, you’re not gaining the skills you need for life,” she said.

As a former high school teacher, Cory Bennett sees some potential advantages to longer periods. He taught in 75-minute blocks, and would have preferred even more time to go into depth. Now an associate professor with Idaho State University’s College of Education, Bennett says the key is using the longer periods to dig deeper into concepts, and allowing students time to collaborate.

But that doesn’t mean the four-day schedule comes without a tradeoff.

“There could very well come a tipping point,” he said. “You need time with content. You need time to think about things.”

A recruiting tool?

According to a 2013-14 National Education Association report, only two states pay lower average teacher salaries than Idaho. Most four-day districts didn’t even meet Idaho’s modest 2014-15 average of $44,739. This suggests the four-day schools tend to hire young, inexperienced teachers — and tend to lose experienced teachers to other jobs.

But some superintendents see the four-day calendar as a way to compete.

That’s the case in Preston, just north of the Utah line. About 40 to 50 percent of Preston’s teachers live in Utah, superintendent Marc Gee said, and pass up five-day jobs in their home state that could pay them $10,000 more a year.

On average, the Mackay School District’s teachers have been on the job for 15 years. The four-day schedule helps recruit teachers to a remote community in the sparsely populated Central Idaho mountains. “It kind of takes a unique person to move to Mackay, Idaho,” superintendent Leigh Patterson said.

The Magic Valley’s Richfield School District also believes the four-day calendar helps with teacher retention; Richfield has lost only one teacher over the past two years. “And I know one of our strongest core teachers chose us just because of our moving to a four-day schedule,” said Superintendent Mike Smith.

With all this in mind, the Magic Valley’s Hagerman School District adopted a four-day calendar in 2014-15 — to compete with three other four-day districts in Gooding County.

But all the talk about schedules as a recruiting tool leaves Idaho Education Association President Penni Cyr skeptical. The teachers’ union has no position on four-day schools. But in the end, she believes her members are drawn to well-funded schools, and district leaders who “respect them as educators.”

Do kids adapt?

Ultimately, the four-day calendar isn’t just an adjustment for teachers, and the administrators who hire them. Day after day, the calendar directly affects students.

Sometimes, the adjustment lingers, years after the switch. “I think Mondays are a little slower,” said Kaden Kunz, a senior at Preston High School, which went to a four-day calendar in 2011-12.

But the smaller the kid, the bigger the adjustment. And as with most issues surrounding the four-day calendar, the evidence skews to the anecdotal.

Said Barnes, the Preston third-grade teacher, “Kids are the most adaptable human beings around. … They rise to the occasion.”

Brooke Palmer sees it differently. She remembers that 2011-12 school year in Preston, when she sent her daughter Serena to first grade. ’’It was like her personality was asleep. … She was just run too hard.” Palmer said Serena didn’t get back to herself until summer break.

At that time, Palmer was a classroom volunteer and substitute teacher. In May, she was elected to the Preston School Board, which spent several months reviewing the four-day schedule.

On Nov. 18, the board voted 4-1 to keep the four-day schedule. Palmer voted — with reservations — in favor of the four-day week.

“Rescheduled Education” is the product of a partnership between Idaho Education News and Idaho Public Television. Reporting on the series are Kevin Richert and Clark Corbin of Idaho Education News and Seth Ogilvie and Melissa Davlin of Idaho Public Television. Video producers are Andrew Reed of Idaho Education News and Troy Shreve of Idaho Public Television. Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader compiled data for the series.

‘Rescheduled Education’ at a glance

Day One, Monday, Nov. 16

An unproven experiment, involving 26,881 Idaho students

Data dive: Surprising statistics on four-day schools

Day Two, Tuesday, Nov. 17

Four-day school test scores are inconclusive — but troubling

Sage and COSSA Academy: Two four-day outliers

Day Three, Wednesday, Nov. 18

A schedule change saves money. Just not much.

Preston upholds a decision driven by dollars

Day Four, Thursday, Nov. 19

Teachers and students adjust to longer school days

‘No time to waste:’ Notus runs at a fast pace

Day Five, Tuesday, Nov. 20

Across rural Idaho, four-day weeks become routine

Challis embraces change — but with reservations