Two teachers who wrote the proposed science standards rejected by the Legislature are standing up for their work and their methods.

Jason George and Christopher Taylor said they are concerned because Idaho’s existing science standards are vague and broad. They’re also confused by why the House and Senate education committees, in a rare action, rejected the standards with little discussion or public input.

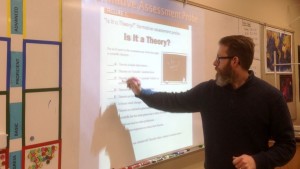

“If you listen to the talk, the talk is always about getting more kids in the STEM pipeline and needing to get kids to go to college,” said George, a 15-year veteran teacher and head of the science department at Vision Charter School in Caldwell. “We have all these lofty goals, but we don’t have standards with enough rigor that would actually prepare kids for those things.”

Both teachers cited a scathing, outside review of the standards by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

In 2012, the institute reviewed the existing science standards in all the states and Washington, D.C., alongside the NAEP framework.

Idaho ranked 44th out of 52 and received an “F.”

“The Idaho standards are remarkable in their almost total disregard for the essential content necessary to educate children in the sciences,” the report’s authors wrote.

Taylor, Boise Independent School District’s science and social studies supervisor, said the new standards would have provided that level of rigor. The teachers focused on three areas designed to make students more science literate — science practices, crosscutting concepts and content.

“That was the whole purpose,” Taylor said. “I feel the current science standards are very broad and there is precious little science in there, to be honest.”

When lawmakers rejected the standards, they said they were concerned that not enough public input was gathered as the standards were developed, vetted and set. But state documents show education officials followed the legal procedures for gathering public input, bringing the standards before the State Board of Education during an August public meeting and soliciting further written public comment during a 21-day period in October.

Although lawmakers essentially avoided public discussions about the content of the standards, one lawmaker questioned language stating “human activities have significantly altered the biosphere, sometimes damaging or destroying natural habitats and causing the extinction of other species.”

“Significantly?” Twin Falls Republican Rep. Lance Clow said during a Feb. 2 committee hearing. “Compared to what? … I think you could write standards without using some of that terminology and still have appropriate science standards.”

George is suspicious that concerns over global warming and the history of the universe derailed the standards.

“If somebody is just scanning the document for one or two things they find controversial and making a decision based on that, I don’t know what we could really put together at that point that would satisfy those people.”

How the process unfolded

In early 2015, the State Department of Education pulled together a committee of science teachers to begin drafting new standards, a practice that typically takes place every five years.

The committee that developed the standards in question included 14 Idaho science educators, among them George and Taylor. Other panelists included a resident of the Midvale School District; Angela Hemingway, the former State Department of Education assessment director, who now heads Idaho’s new STEM Action Center; Scott Cook, the SDE’s director of academic services; and Scott Smith, the SDE’s science coordinator. Taylor and George said they also met with or gathered input from Idaho National Laboratory, Boise State University and University of Idaho experts.

The committee included some of the state’s decorated teachers. Two received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science and Math Teaching. George is one of Idaho’s current nominees for the Presidential Award, and has won the Governor’s Industry Award for Notable Teaching in STEM.

“These are excellent science teachers,” George said. “I’d like to have all of them on my staff.”

Once the committee was seated, teachers compared the existing standards to the Next Generation Science Standards developed by the National Science Teachers Association and National Research Council, George said.

The Idaho teachers then reviewed assessments, specifically the biology end-of-course assessment, to probe alignment of the standards to the tests.

They also sought to develop a logical sequence, so standards for high school were built upon the standards for middle school, which were built on the standards for elementary school.

George estimated the teachers put in two eight-hour days when the entire committee met in Boise, with individual members contributing 15 to 20 additional hours of work and research between the meetings.

Where it derailed

The standards arrived intact for the 2016 legislative session, taking the form of an administrative rule that also included new humanities standards.

On Feb. 2, House Education Committee Chairman Reed DeMordaunt, R-Eagle, urged his committee to reject the standards.

“I feel we can do a better job than what we’ve done in terms of getting feedback from our citizens in regard to this,” DeMordaunt said. “My recommendation is we reject this rule and allow our citizens to participate more fully in the process.”

New Plymouth Republican Rep. Ryan Kerby, the retired superintendent of his local school district, then praised the standards as “inquiry-based,” “fabulously written,” and full of data analysis that should spark critical thinking among students.

“The work was, by and large, really nicely done,” Kerby said. “Thank you.”

But, a moment later, committee members voted to reject the standards and adjourn.

Fast forward to Monday. The Senate Education Committee had its turn to consider the standards.

Taylor was in the audience, along with four high school students. He hoped to testify and give lawmakers an idea of what was in the standards and how they were developed.

Before he could do so, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Sherri Ybarra’s special assistant Tim Corder said Ybarra personally asked the committee to reject the standards.

The state followed “the letter of the law” when it comes to public notice and comment, Corder told the committee, but it’s up to the public and lawmakers to decide whether that was adequate.

“Sometimes it is the spirit (of the law) and not just the letter that counts,” Corder said.

With that prompt, Sen. Janie Ward-Engelking, a Boise Democrat and former teacher, led the bipartisan effort to reject the standards.

Senate Education Committee Chairman Dean Mortimer, R-Idaho Falls, never called on Taylor or anyone else who sat through the meeting hoping to testify.

“I wanted them to understand the process,” Taylor said.

The standards were rejected on a unanimous voice vote. Taylor walked away confused.

“It was pretty vague about what we needed to do differently with the process,” he said.

The content

The science standards are 109 pages long.

They are broken down by grade levels and cover the Earth’s place in the universe, biology, molecules, organisms, sound waves, forces of motion and much more.

Throughout, connections are drawn to Idaho’s existing math and English standards. The authors also list student performance expectations, such as “make observations to determine the effect of sunlight on Earth’s surface.”

The standards also reference the age and creation of the universe, humans’ role in climate change and evolution.

Corder speculated that those subjects “may have been what motivated people to take issue with them.”

But George pointed out those subjects already appear in the state’s existing science standards. Under Standard Five, Personal and Social Perspectives, students are asked to “understand common environmental quality issues, both natural and human induced.” Under Standard Three, Biology, students are asked to “use the theory of evolution to explain how species change over time.”

George and Taylor both said it is completely scientifically appropriate for students to deal with those subjects.

Furthermore, Taylor said the science teachers’ goals were to prompt students to use the scientific method, data analysis and critical thinking skills to draw their own conclusions on subject matter.

“It’s very difficult to say, ‘You can’t teach biology without discussing evolution,’” Taylor said. “And there is so much data on climate change. Whether you believe it is from human impact or not, it is there, it’s happening. We need to have those in there and our kids need to look at those claims and evidence.”

Those subjects aren’t very controversial within the scientific community, George said, but he recognizes they are sensitive subjects within political and social circles. Nevertheless, George said he would have welcomed more feedback into the process.

What’s next?

Rejecting the standards means they are dead for 2016, and Idaho schools will continue to use existing standards that the Fordham Institute described as “useless for all the purposes for which science standards are intended.”

It was not immediately clear what state leaders will do next.

Corder said one option is to stage a series of public forums across the state to gather feedback.

So far, legislators have not called for rewriting state laws and administrative rules governing the process for developing and vetting standards. So far this session, they approved nearly 100 pages of other administrative rules that were subjected to the same public input process, without raising any concerns.

George worries retaining the existing standards will hurt new teachers who have to apply them to lesson plans. He is also worried for science students.

In the end, he said he did his best to correct what he views as a problem, and he absolutely stands behind the process the science teachers followed.

“I put my name on something, saying I feel like I did everything I could to prepare these kids for college,” George said.