Melody Campbell’s first-grade son struggled with reading last year.

Frustrated that he couldn’t decipher words fast enough, impatient to know what stories said, he would try and guess his way through sentences instead of stopping to sound out the words.

So teachers at Chief Joseph School for the Arts got to work. They helped the boy set reading goals. He participated in daily skills groups where he learned with other students who needed help in the same areas. And they gave Campbell resources to help her son practice at home.

This year, Campbell’s son loves to read. He’s caught up to grade level, and isn’t afraid of the no-picture books that might have overwhelmed him last year, his mother said.

“It’s just such a huge difference,” Campbell said. “He definitely has much more confidence now.”

Just over half of Chief Joseph’s kindergarten through third grade students could read at their grade level when they started school in the fall of 2018.

By the time those students finished their school year, in the spring of 2019, 84 percent of them were up to speed — an average that outpaces the West Ada school district and the state of Idaho.

These results, and similarly high results on English and Math standardized tests, netted Chief Joseph a prestigious National Blue Ribbon award from the U.S. Department of education this year.

The West Ada school, which serves a high volume of low-income students and English language learners, was recognized as an Exemplary High Performing School.

It was one of two Idaho schools to win the distinction.

“We’ve always had a great core of families and staff and kids,” Principal Gretchen Hart said. “What we’ve worked really hard on is coming together as a team to keep kids’ needs foremost.”

The last decade has seen quite a transformation for Chief Joseph which, in 2011, was in jeopardy of facing state sanctions if student achievement didn’t improve.

Hart, who started as principal of Chief Joseph in 2012, calls the turnaround a team effort, driven by setting goals, keeping high-standards and “knowing, loving and growing” every child.

“No child is a stranger here,” Hart said. “We know them all by name, and we know all of their needs.”

Kerry Nishikawa, a long-time Title I teacher at Chief Joseph, said Hart’s emphasis on goal-setting has helped encourage students and teachers at the school to aim high.

“It was able to energize everyone to want to get that much better,” Nishikawa said. “The students take ownership of learning now that they have a goal set, and they know what that needs to look like.”

Goal setting is just one of the strategies Chief Joseph School for the Arts employs to boost student progress.

Every day students have 30-minute skills groups in reading/writing and math, where they focus on mastering skills that they struggle with. Teachers use internal and state tests to gauge student’s progress, and meet in grade-level groups to analyze that data and set goals for improvement. As a school of choice for arts education, Chief Joseph also incorporates art in daily classroom work and gives students 45 minutes of art education each week.

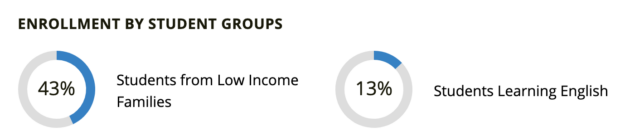

Many of Chief Joseph’s 500-some students come from low-income households, or are learning how to speak English, both factors that can challenge a student’s academic achievement.

At Chief Joseph, children in each of those groups outperform state averages.

Because of its high rate of low income students, Chief Joseph qualifies as a Title I school, meaning it gets federal funds to help low income students succeeds.

Fifteen years ago, when school counselor Tirsha Marquart first started at Chief Joseph, the school didn’t get that extra help. Today, she’s able to connect students with food, healthcare, school supplies and more. Earlier this week, she took a group of students to pick out warm winter coats.

“The kids are the same, but they take more pride in their achievement,” Marquart said. “They’re able to focus on that as we learn more about helping them through other issues that they have.”

Kathy Gutierrez, a paraprofessional who works with English language learners at the school, said the team approach to helping students and families sets Chief Joseph apart.

“All the teachers want students to succeed. If they see a student failing they’ll come talk,” Gutierrez said. “What can I do? What can we do as a group?”

The school has built trust with families to the point that parents who don’t speak English regularly attend school gatherings, Gutierrez said.

“Diversity is really a strength for us,” Hart said. “I think it makes our students more open minded and curious, which makes them better learners. Never would I want to have our English learners go to any other school.”