CALDWELL — Armand Nance sits near the cafeteria entrance at Elevate Academy on weekday mornings, checking students’ temperatures as they arrive.

Cinthia Villanueva, a new staff member hired to help ward off COVID-19, walks the halls with a spray bottle in hand, sanitizing door handles and stair railings and shared bathrooms.

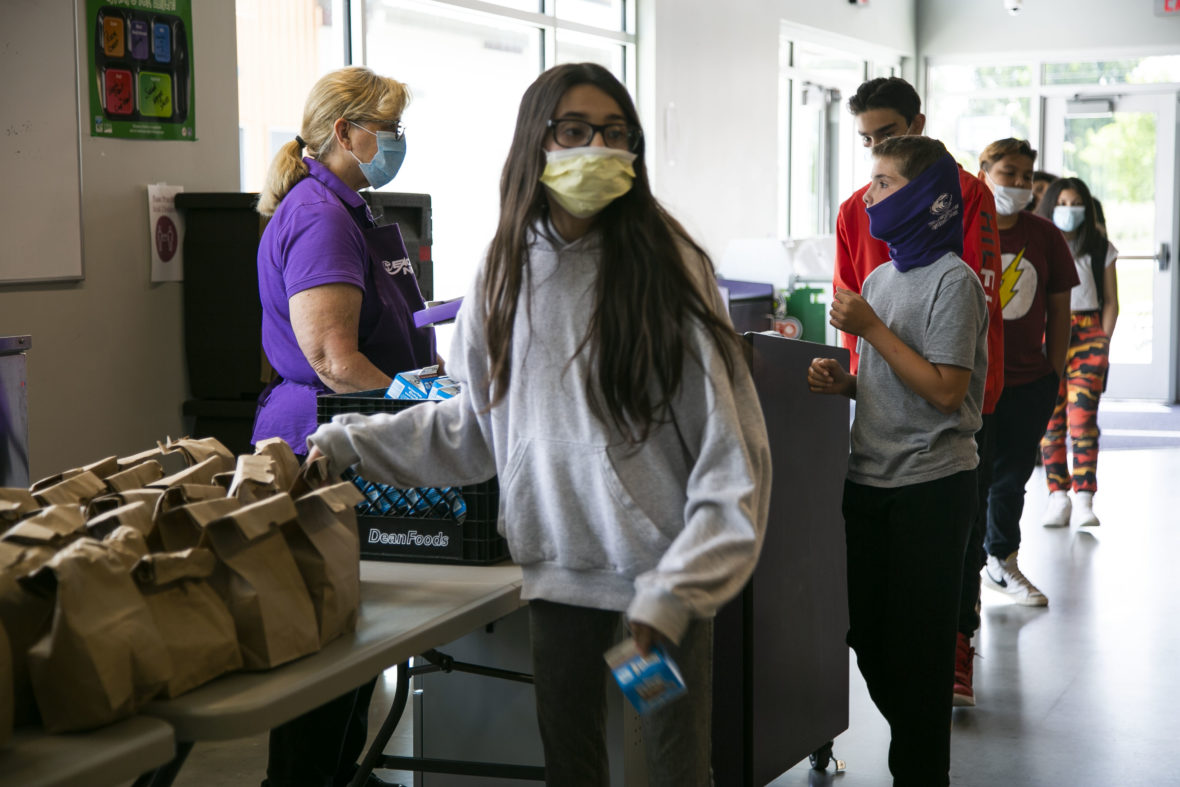

In the kitchen, Debbi Nisula packs sandwiches into brown paper bags. Kids used to visit her salad bar or stop at her serving line for a hot meal. Now they grab a pre-bagged lunch wrapped in disposable materials, then sit down at cafeteria tables where every other seat is marked off-limits with a taped “X.”

These are scenes from inside a school building that reopened during a global pandemic.

Elevate Academy, a year-round, 300-student public charter school in Caldwell, opened with a modified schedule on June 1, the first weekday after Gov. Brad Little authorized gatherings of more than 10 people. The charter school hadn’t even finished its first school year when the pandemic hit. Elevate opened last fall with a specific focus on serving at-risk youth in the Treasure Valley through career and technical education.

Administrators decided to reopen, in part, so they could continue to offer hands-on career and technical training, which is difficult to simulate from home. But the driving factor was student behavioral health. Five of Elevate’s students attempted to take their own lives while school was closed, administrator Monica White said. Eight students were placed in, or referred to, foster care.

“There’s a lot of stuff going on with kids being home all the time. The mental health part is really important to us. If we’re here, at least we have our finger on it,” White said. “There’s a lot more to school than just the books and the education.”

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, text or call the Idaho Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-208-398-4357.

In the past two weeks, Elevate students and staff have developed a new routine, using temperature checks, sanitation and distancing to try to ward off the threat of the novel coronavirus in Canyon County, an area that has seen community transmission of the disease. Still, the routine isn’t perfect. Kids walk shoulder to shoulder down the hallways, forget to pull up their masks in close proximity and get physical on the basketball court. Teachers frequently remind them to spread out.

“Did you guys wash your hands?” a teacher asked middle-school students who streamed down the hallway toward lunch Tuesday. “Remember, six feet apart,” he told them as they lined up to grab their paper sacks.

Administrator Matt Strong said students are getting used to the new rules — but enforcement takes ongoing effort.

“You’re talking about kids that love each other, that want to be around each other, who are spending time together on the weekends, trying to get them to social distance,” Strong said. “You’ve got to work at it.”

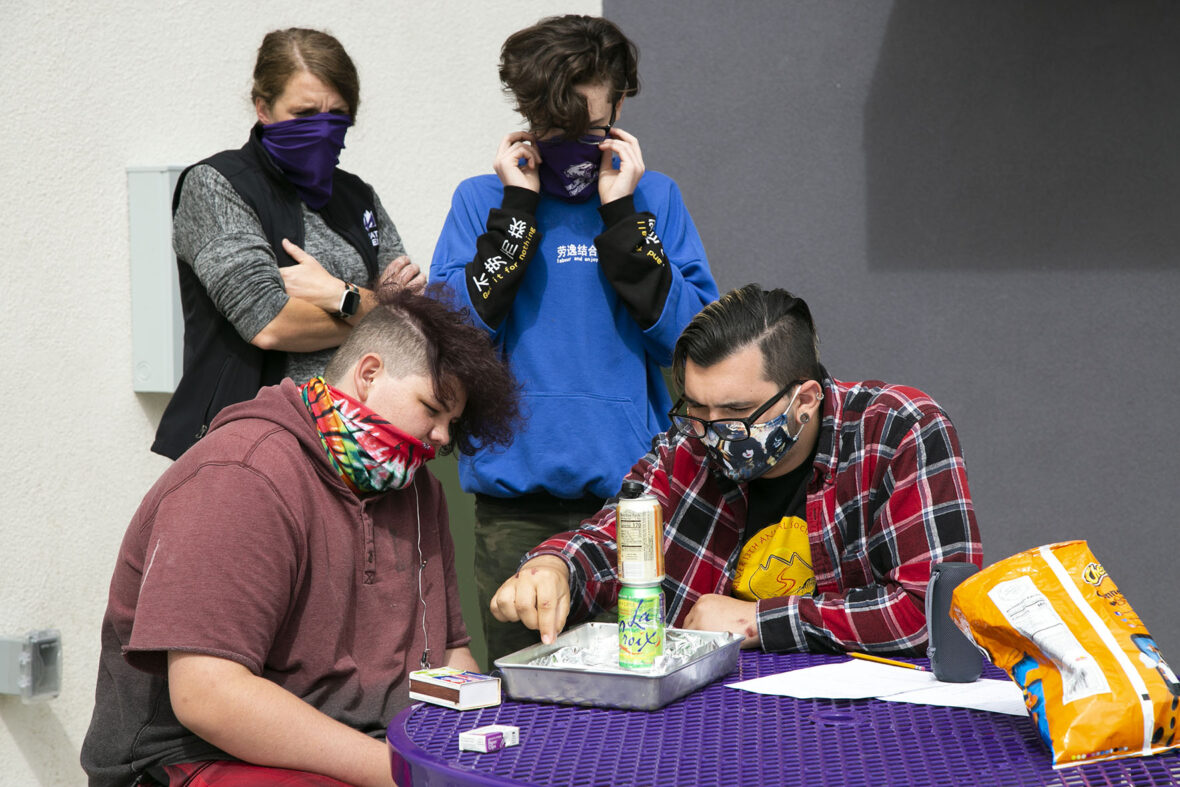

Only half of the Elevate’s students are at school on any given day, dropping already small class sizes down to seven or eight kids. Students spread out within classrooms wearing personal or disposable masks around their faces or necks.

Greg Cocozza, Elevate’s residential construction instructor, asks his students to keep their masks on in his CTE class. Generally, he said, they respect that.

Cocozza was hesitant to come back to work in person. He wanted to wait and see how Idaho’s cases would increase or decrease before returning to school buildings too quickly. If Cocozza had decided he didn’t want to teach in person, White said she would have hired an aide to watch his classroom while he taught virtually.

It was talking to White about student circumstances that helped Cocozza make up his mind.

“Getting them out of their homes can really be a great thing, getting their heads geared back toward school,” he said. “I knew the risk side, but once I understood the rewards side it helped me make an educated decision.”

Tey Kruckman, a 10th grader at Elevate, was likewise nervous about the return.

It wasn’t because of school — Kruckman enrolled at Elevate in the fall because her anxiety made it difficult to thrive in large class sizes in the Caldwell School District. At Elevate, Kruckman says she has come out of her shell. She’s making more friends, she helps in the kitchen and is part of the student council.

Kruckman was nervous because she and her family are high risk if they catch the coronavirus. She has diabetes, lives with a toddler, a senior, a family member with a severe disability and others who have compromised immune systems. But during the school closures, Kruckman struggled with distance learning. She had to force herself to do work, struggled to focus on the computer and felt like she was slacking.

She decided to come back to school when Elevate reopened, despite the risk.

“I was nervous because it was going to be stressful,” she said. “Everybody was going to want to be near each other, but we have to keep ourselves distanced and clean.”

Kruckman says she feels confident that Elevate is taking precautions to keep her safe. The return has been an emotional boon, too. Staying at home can trigger Kruckman’s depression and anxiety, she said, and she can fall into bouts of crying, sleeping, and moping around the house.

“Coming to school I haven’t had those episodes,” she said. “I’m not being worried that I’m staying at home annoying people too much. I know that here, I’m welcome.”