EDITOR’S NOTE: Eleven Idaho schools are launching on an experiment this fall. They are using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools. This is the fifth of a series of stories on the grant recipients.

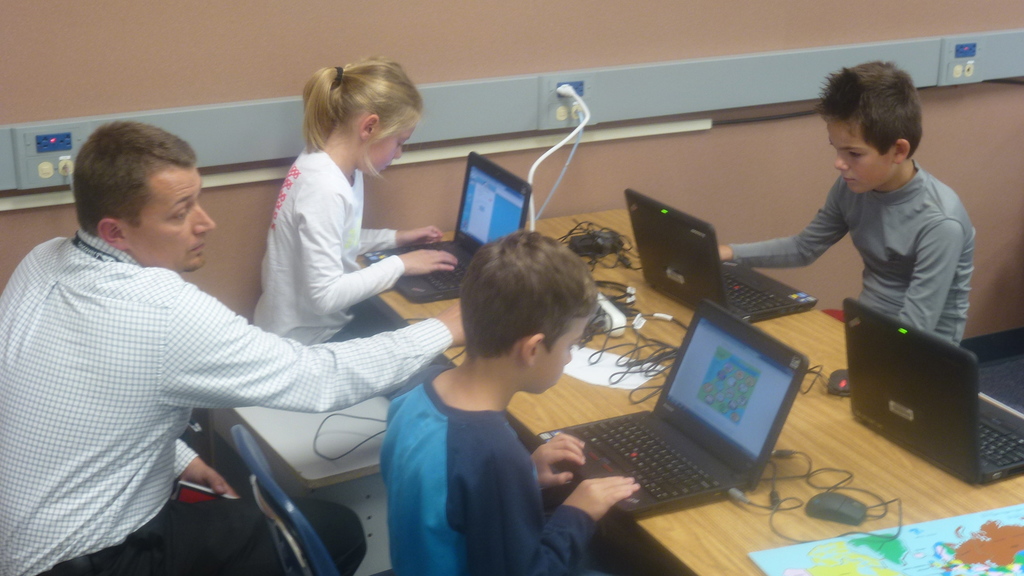

Can schools incorporate technology in classrooms — and encourage kids to collaborate in small groups?

That’s the essence of the $370,501 technology pilot project at Meridian’s Discovery Elementary School, a project designed to transform classrooms by breaking them into several smaller classrooms.

At any given time, a couple of groups might work on some of the school’s newly acquired mini-iPads, while another group works at a bank of desktop computers, while other groups work on old-fashioned paper worksheets. Then, within a few minutes, the students switch from one station to the next.

And all the while, teachers are on the move, giving students closer attention than they would receive in a traditional classroom structure. “Small groups make a huge difference,” said Lisa Bray.

A rapid rollout

Bray has taught for six years at Discovery, and her connection with the children is evident. When she walks the hallways, she is frequently flagged down by students who want to say hello or get a hug. When she talks about the school — and the technology program — she affectionately refers to the students as the “kiddos.”

She spends her mornings teaching second grade. But now she spends her afternoons coaching on the technology pilot. That means, when she walks the hallways, she is also flagged down by fellow teachers who have questions or want to talk to her about the project. Often, she offers a second set of hands in a classroom.

The rollout has unfolded quickly. The State Department of Education announced the 11 pilot projects on July 1 — during a ceremony at Discovery. School officials scrambled to purchase and prepare equipment for the first day of school Aug. 27.

All the equipment was on hand for the first day, she said. While the rollout has included some “baby steps” and some trial and error, as expected, Bray is seeing some changes already. Teachers are collaborating more, and across grade levels, about how to implement the technology. And the “kiddos?” They’re talking more excitedly about their classwork — and picking up on the technology quickly. “I still stand back, and I’m just amazed,” Bray said.

Academic goals

Discovery is a three-star school in the state’s most recent five-star ratings — a year after receiving four stars in Idaho’s inaugural ratings.

The school hopes its technology program will address a wide range of academic issues.

Writing skills are an “identified weakness,” Discovery said in its grant application — a skill that is all the more important with the new Idaho Core Standards, which emphasize writing both in English language arts and math. Discovery also wants to boost science skills; help students with disabilities, who have struggled on the Idaho Standards Achievement Test in math and reading; and push students who are already scoring well on assessments.

A rotational approach

Discovery calls its technology plan a “rotational model,” with purchases to match.

In a school with enrollment of nearly 600, the school consciously decided to buy 214 laptops. The school purchased 218 iPad minis — smaller than the standard tablet, and a better fit for elementary students’ hands. “(It’s) more their size,” said Bray.

The idea wasn’t necessarily to downsize costs. But in its grant application, Discovery touts the rotational model’s affordability. Over five years, the program should cost about $126 per student per year, with costs gradually dropping as teachers receive more training.

The overriding advantage to a rotational model is collaboration, Bray said. A one-to-one model — with individualized devices for every student — encourages students to work independently. That has its advantages, she says, but it also gets in the way of collaboration.

Breaking down classes

In Meridian – the state’s largest school district – class sizes are a perennial concern. Technology cannot change class sizes, but it can change the dialogue between teachers and students.

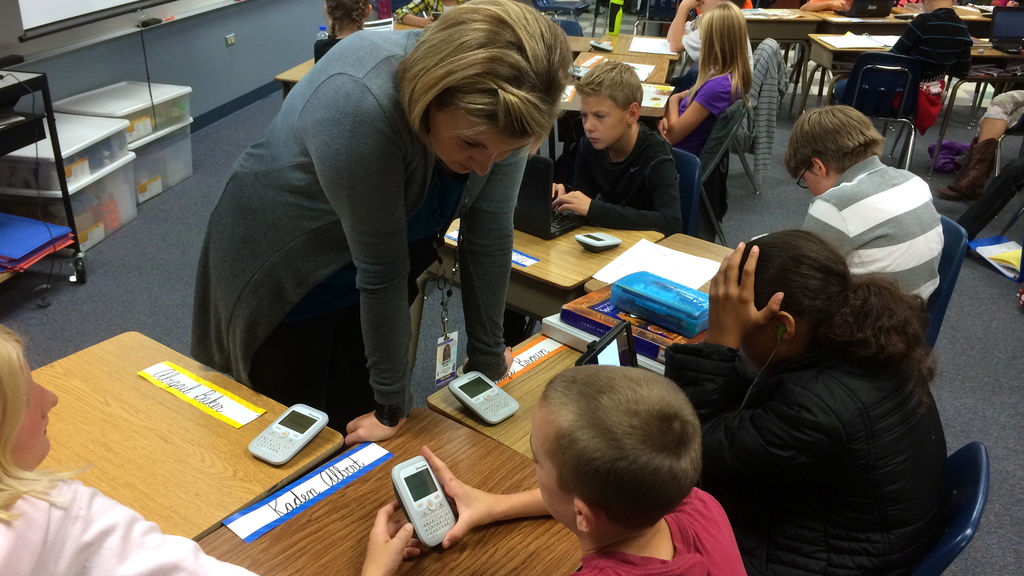

Last week, Lauri Wright used some of the school’s new technology to get a read on the 31 fifth-graders in her class. She asked them to define protons, neutrons and electrons, and share their responses not on paper, but electronically.

The class used “student response” devices, a $38,400 component of the Discovery grant. Similar in size and shape to a desktop calculator, the devices enable students to text in answers. Teachers can see the responses immediately, save them in a spreadsheet. They can also share the responses with the class, as Wright did, by posting them on a projector.

Still, the centerpiece of the rotational model is small group work. For Bray, that means she will shuffle her class throughout the year – blending students who are at different skill levels, and mixing up the groups to keep the class from forming into cliques.

In a large school in a large district, this is no small transformation.

“Today’s classrooms are characterized by lecture-driven, teacher-directed learning delivered to the masses,” Discovery says in its grant application. “Our plan will transform Idaho education by creating a more student-focused model of instruction.”

More stories about the 11 Idaho schools using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools: Learn about Kuna Middle School’s Chromebooks project. Learn about Middleton High School’s laptop pilot. Learn about attempts to reverse achievement gaps at Parma Middle School. Learn about a writing emphasis at Weiser’s Park Intermediate School.