The students in Angie Grant’s fourth-grade class listened intently, nestled amongst handmade pillows in Grant’s reading area, while she told a story about the Norse god Loki. Now they’re trundling back to their desks on the other side of the classroom, pulling out their class materials and singing a song to the tune of “Oh! Susanna!”:

I’m a Viking, for that’s the thing to be! For there’s no greater joy than pirating for a Norse warrior like me.

Welcome to Syringa Mountain School. This Waldorf-inspired school in Hailey is Idaho’s newest public charter school, and as such it faces some steep challenges: It’s using a curriculum traditionally taught in private schools, yet must adapt it to meet Common Core academic standards; it opened in August and has had to design nearly everything, from its interior building design, to its outdoor garden, to its teacher training and development.

Welcome to Syringa Mountain School. This Waldorf-inspired school in Hailey is Idaho’s newest public charter school, and as such it faces some steep challenges: It’s using a curriculum traditionally taught in private schools, yet must adapt it to meet Common Core academic standards; it opened in August and has had to design nearly everything, from its interior building design, to its outdoor garden, to its teacher training and development.

“It’s a wonderful responsibility to have,” says School Director Mary Gervase, who initially became involved with the school as an education consultant. “I just feel so honored to be part of it, as I think everyone does here.”

A new way of thinking about an old curriculum

Traditional Waldorf education is based on the methods of Rudolf Steiner, who launched his education philosophy in Germany in 1919. Steiner’s method stresses the natural development of the child and breaks it up into three distinct phases: birth to 7 years, 7 to 14 years and 14 to 18 years. Waldorf methods emphasize handwork, the outdoors, movement and storytelling. It is one of the fastest growing educational models in the world. There are more than 250 such schools in North America, but Syringa Mountain is Idaho’s first public Waldorf school.

“The way Waldorf is set up, children developmentally need certain stories at certain ages,” Grant, the fourth-grade teacher, says. “For Norse myths, it brings in all these characters that make children question their character. Such as Loki, who is very sweet and kind and smart and very crafty and sly. So the children can relate to these characters. I can say, ‘Oh, you’re really being like Loki today!’ And they can stop and think and say, ‘Maybe I am being a little sly today.’ It’s very interesting to watch.”

Those stories are integrated throughout the day. Later, children in Grant’s class created pictures of Loki and replaced his hair with adjectives to describe the god, which carried the myth into the language arts.

“The curriculum, I feel, is really rich in that we use source material in mythology and biography components,” says Mende Coblentz, Syringa Mountain’s curriculum director. “It creates a rich world literacy.”

As they progress, students move from fairy tales and Hebrew and Greek mythology, eventually integrating Idaho, national and world history.

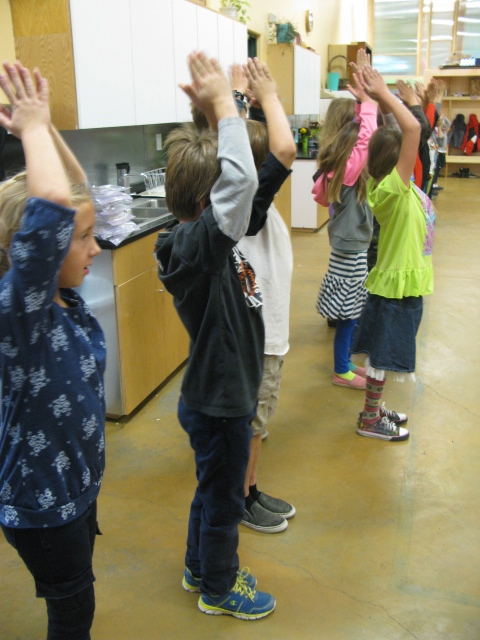

Syringa Mountain, like traditional Waldorf schools, places a lot of importance on natural materials. Everything is tactile. Students mold, paint, sculpt, whittle and move their bodies — a lot. The crayons are natural beeswax rather than Crayolas. The classrooms are hand-painted in designs and landscapes by parents, volunteers, and students. The kids learn science, in part, by working in the school’s garden. The children reproduce their best work in lesson books, which are then bound and given to their parents at the end of the year. The chalkboards are old-fashioned blackboards.

“We’re really low-tech,” Gervase says. “Part of the Waldorf training is that you learn how to do chalkboard art, you learn how to do painting, figure drawing — that wasn’t part of my training, you know?”

Training has been an issue for Syringa Mountain from the start. There are no Waldorf training centers in Idaho or nearby states, so Gervase and the school’s board decided to bring trainers to Idaho. This past June, all teachers went through a two-week intensive with three professors recruited from Kentucky. Gervase says that process will continue for the next three years until all of Syringa Mountain’s teachers are certified in the Waldorf method.

“The unintended benefit was that we had teachers traveling here for the training,” Gervase says. “We had teachers coming from Montana, we certainly had a contingent from Boise, interest from Salt Lake. So we’re the closest Waldorf training center for the surrounding states. That’s really our hope — that we’ll continue to be a training center, specifically for public Waldorf schools.”

Unlike private Waldorf schools, however, the students at Syringa Mountain must meet or exceed Idaho public education standards, and the methods needed to assess students don’t fit into the traditional curriculum. Take computers, for example, which are used during Idaho’s Common Core assessments. At a Waldorf school, students in younger grades are virtually tech free.

“In private Waldorf schools, they wouldn’t even use it until middle school,” Gervase says. “But as a public school, we are required to participate in all of the state assessments, so as a result we will be introducing at least computers starting in third grade.”

Part of Coblentz’s job is to help integrate Waldorf methods with the Common Core. “Any time you blend the two methods, you’re going to have to adapt,” she says. “You’re going to have to speed something up, slow something down, chuck one thing and invite another thing in.”

Students at Syringa Mountain tend to be more advanced mathematically than students at traditional public schools but a bit delayed in reading, which isn’t introduced in Waldorf-method schools in early childhood.

“Fourth grade is where we even out and the curriculums really become quite similar,” Coblentz says.

It’s all part of a process of working with an older educational method, she says.

“You constantly have to upgrade and update to keep up with the times,” Coblentz says. “Education changes because we change over time.”

Syringa Mountain attempts to keep Waldorf alive in the Wood River Valley

The Syringa Mountain School was born out of the ashes of the Mountain School, which was located near Bellevue.

“It was just sort of the perfect sequence of events,” says Gervase, who once served as the assistant superintendent for the Blaine County School District. “There was a small, private Waldorf school here with about 40 children and it was closing. The way this all got started was that a group of parents came to me and asked me if I would help them write a charter. That school was closing, these parents wanted a Waldorf option for their children, so we didn’t have any time to lose.”

The Syringa Mountain founders initially considered opening as a magnet school within the Blaine County School District, but, given the impending closure of the Mountain School and immediate need for an alternative, decided to go the public charter route instead. The Blaine County School District referred the founders to the Idaho State Charter School Commission, which accepted Syringa Mountain on its first application in August 2013. Idaho First Lady Lori Otter joined the school’s advisory board in April 2014.

Annie Bloomfield, whose two daughters, Grace and Gaby, attended the Mountain School, moved her youngest to Syringa Mountain when the school closed. Grace, who is in seventh grade, had to move to a different school because Syringa Mountain is only K-5.

“It just was a fit for both of them,” Bloomfield says of Waldorf. The method was a natural extension of her parenting style, she says, giving children a lot of hands-on and outdoor experience.

“It’s shaping who they are as human beings,” Bloomfied says. “They have reverence and respect for each other, the kindness that you show another person, reverence for the outdoors, for nature, for earth, and how we’re all part of this big, beautiful world together.”

Now, Bloomfield says, her daughters are hopeful that Syringa Mountain will continue its planned expansion. The school would like to include grades 6-8 by 2017; it currently has about 135 students and a waiting list of 5-10 families.

That’s not the only way Syringa Mountain would like to expand, however. The board’s strategic plan includes a goal of reaching a three-star rating or higher through the Idaho State Department of Education (assuming the state keeps its star-rating system); further build out of the school’s campus (currently housed in a business park); and development of deeper roots within the Blaine County community.

Syringa Mountain is also considering education throughout the Wood River Valley. Greg Bloomfield, chair of the Syringa Mountain School Board and husband of Annie Bloomfield, recently sent a letter to Blaine County School District asking them to consider an “uncharted” new option that would benefit public charter, magnet, and traditional schools.

As the Idaho Mountain Express reported in mid-December, Greg Bloomfield also read the letter aloud at the Blaine County School District’s monthly meeting. Board Chair Shawn Bennion “responded in writing to the Bloomfield letter, stating that the School District will research state law that might pertain to a union of the district and Syringa and would consider the proposal in its new strategic plan that will be developed in the first half of 2015,” according to the Mountain Express.

It would be a big move for a small school, but such thinking is typical of Syringa Mountain’s broad outlook.

“I think one of our challenges is to try to figure out, What does Waldorf education look like in the 21st century and beyond?” Gervase says. “This is one of those things we’re learning about. I’ll let you know at the end of the year how it goes.”

This is the third in a six-part series featuring Idaho charter schools. The first was about Boise’s Anser Charter. The second was about White Pine. This series is being provided by the Idaho New School Trust, which is funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation.

Disclaimer: IdahoEdNews.org is funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation.