This is one in a series of stories featuring what some of the nation’s top-performing high-poverty schools are doing to boost achievement among all students.

SPANAWAY, Wash. — Teachers Lynn Taylor and Karie McVey could hardly contain themselves when the state test scores came in. He’d done it.

“We jumped up and down,” Taylor said. “I mean, hyperventilating when we got the results because you never would have thought. And he did it.”

All year, the fifth-grade educators kept after a struggling student who read far below grade level, rarely completed his work and had little support at home.

None of those challenges were reason enough for the teachers to lower their academic expectations for the boy. Not at Evergreen Elementary, where “no excuses” is the law of the land.

So, if he didn’t turn in his homework, they’d keep him in class to get it done. If he couldn’t read a word problem, Taylor would read it aloud for him to solve.

“It would be so much easier to go, ‘Ah, nothing is ever going to change with a kid like that. Or, he’s never going to get it,’” Taylor said. “It’s in those moments that you’re like, ‘Oh, this is hard work.’”

It paid off. The boy passed the state exam for the first time, demonstrating proficiency at grade level.

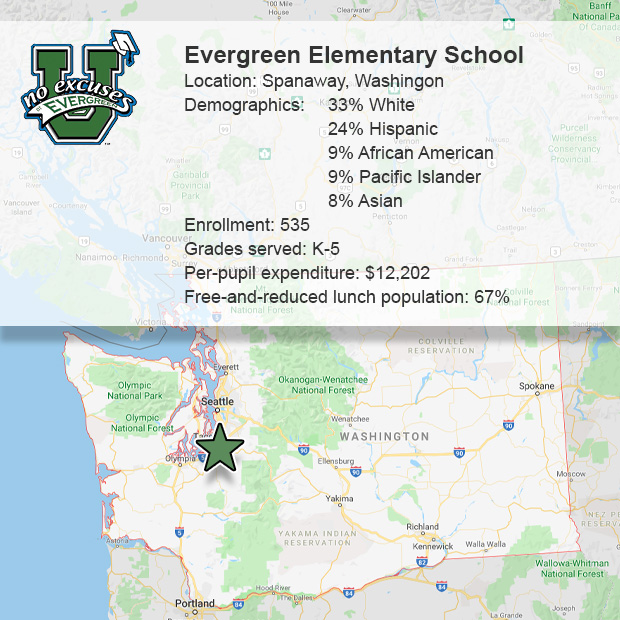

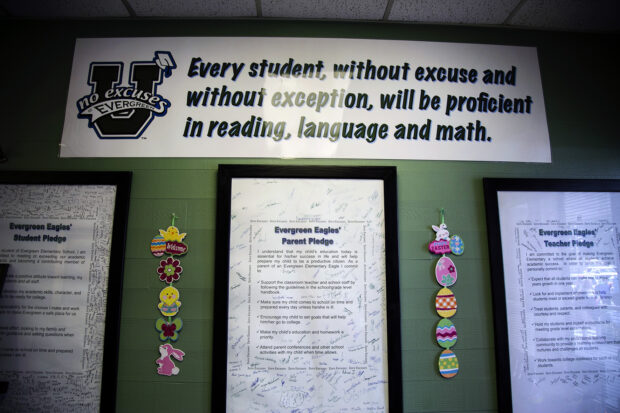

Success is the expectation for every one of the 535 students at Evergreen in Washington’s Bethel School District. The school’s motto is that every student will be proficient in core subjects “without excuse and without exception.”

And most of them are.

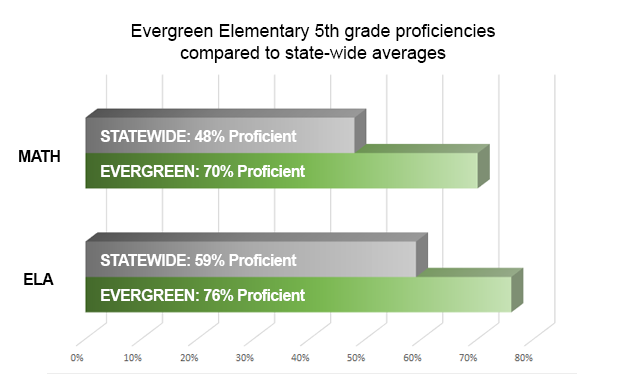

In 2017-2018, 76 percent of all fifth-graders at Evergreen were proficient in English Language Arts, and 70 percent in math. Those numbers were at least 15 percentage points higher than the statewide averages.

It wasn’t always this way at the Spanaway school, which serves a majority low-income student base.

In 2005-06, Evergreen was ranked dead last of Bethel’s 15 elementaries, according to an award application the school submitted to the U.S. Department of Education. That year, fewer than half of the school’s third-graders tested proficient in reading.

“We were literally considered the armpit of the district,” said kindergarten teacher Holly Weik. “…People wouldn’t even sub here it was so bad.”

What Evergreen does differently

In 2010 a group of Evergreen’s teachers went to a conference in California aimed at turning around struggling schools.

They discovered “No Excuses University,” an educational model that aims to prepare every student for college by holding them to high standards and using data to measure and drive student improvement. More than 200 schools across the country use the model, according to the No Excuses website.

“No Excuses” unified the school, Taylor said. Before, some teachers had been making improvements individually; afterward staff members worked together to implement the no excuses model schoolwide.

“We were a well-oiled machine,” she said. “And you could feel it through the school.”

Evergreen officially joined the No Excuses University network — which costs about $130.00 a year in membership dues — in 2011.

As part of the cohort, the school adopted six core systems of No Excuses University and added two of their own:

- Creating a culture of universal achievement: Teachers at Evergreen believe each student can, and will, succeed academically. They demand student buy-in as well.

- Collaboration: All teachers and staff in the building work on committees that evaluate and tweak how things work at the school.

- Standards alignment: Evergreen uses Washington’s Common Core standards as the backbone of the curriculum. Teachers break from the district curriculum where they need to, teaching what they think fits the state standards best. “We are allowed to change it up and nobody squabbles at us because our scores are so high,” Taylor said.

- Assessment: In the first weeks of school at Evergreen every student is tested to gauge their skill levels. Teachers test consistently throughout the year to track individual and group progress.

- Data Management: Class test scores are posted in the hallways at Evergreen. Students know their own scores and are expected to improve.

- Interventions: Twice a day, all students break into Response to Intervention groups to work on math and reading individually, or with others separated into grade level, below grade level, or above grade level groups.

The US Department of Education awards the blue ribbon distinction to schools that have high performing students or have lowered the achievement gap.

The school has also a character-building program in place, which values traits such as trustworthiness, fairness and respect; and a building wide discipline system that requires teachers to enforce consistent behavioral standards, such as a no-talking in the hallways rule.

By 2013, two years after Evergreen joined No Excuses University, the school became the highest achieving elementary in its district.

For its high performance, Evergreen was recognized as a Blue Ribbon school by the U.S. Department of Education in 2018.

What works

Only three of Holly Weik’s 21 students could read when they started kindergarten last year. By April, all but two were finishing books. Her students were writing paragraphs, testing on computers, and building model homes to demonstrate flood resistance.

“We never tell a kid they can’t do something,” Weik said. “You can’t say ‘I can’t,’ anywhere in the building.”

Evergreen is a different environment than when Weik started teaching there 21 years ago. Back then, Weik said, teachers underestimated how well some students could perform because they didn’t have support at home, came from families with generational poverty or had language barriers.

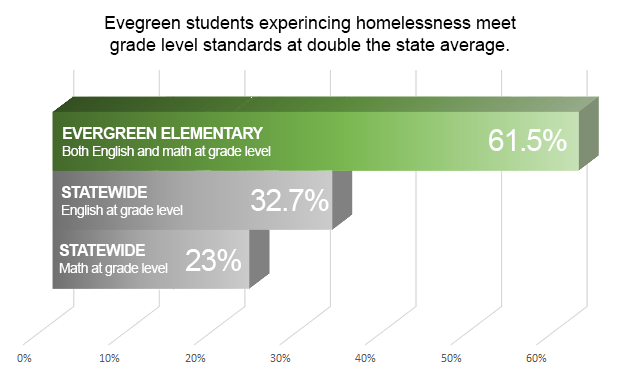

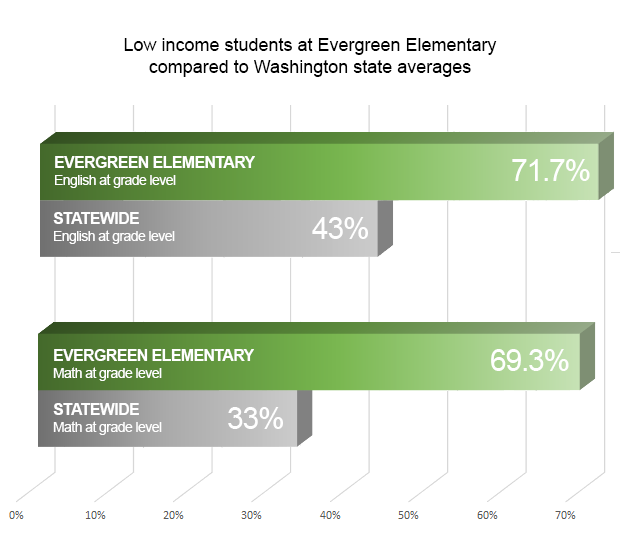

Those challenges still exist. Sixty-seven percent of Evergreen students qualify for free or reduced lunch. In 2017-2018, two dozen of Evergreen’s students were experiencing homelessness and 12 percent of students were English language learners.

What changed, Weik said, was the teacher’s mindsets.

“We stopped blaming them and using that as an excuse, and turned it to where we took all the blame, all the responsibility,” she said. “We got anything they needed so that those wouldn’t be used as excuses anymore.”

Evergreen social worker Allyson Hammes helps families connect with housing, food resources and medical care. She gives children uniforms if they can’t afford them, and will wash clothes for children who don’t have access to a washer or dryer.

Poverty is not a reason for kids to slack in school under the “no excuses” model.

“We get it and we’re here to help you and support you,” Hammes said. “But you are not going to let the ‘low income’ label define who you are. We are going to overcome this.”

According to the data, it’s working.

Expectations are high. Teachers give students alarm clocks if they are regularly late to school. If they don’t show up, staff will sometimes go and get them. Students who don’t do their homework have to stay in from recess. No excuses.

“They’re usually nice when you get all your work done and you’re on task,” fifth-grader Dwight said. But “they can be strict if you just didn’t do your work or don’t try.”

And if a student’s home life is too chaotic or unstable for them to work at home, teachers allow them to come in at 8 a.m., more than an hour before the starting bell.

Every day, a few dozen show up in the morning, even if they don’t need the extra help.

“We think they show up for other reasons. To talk to us. Or be a part of our community,” she Taylor. “Maybe nobody is at home.”

The challenges

Moving to Evergreen comes with a steep learning curve – for new students and teachers.

After the school’s transition into a No Excuses University (a national designation), principal Jamie Burnett said the staff dropped by a handful.

On average, he loses one or two teachers a year who don’t mesh with the Evergreen way.

“It’s the system, it’s the fit, but there’s also teachers that feel peer pressure if they’re not meeting a high level of scores,” Burnett said.

When the school first adopted the no excuses model, Taylor remembers staff members calling each other out during meetings for making excuses.

“It was so hard for people to say those words, and it was even harder for the person who was receiving it to take it, because it was true,” she said.

Today, veteran staff members have those candid conversations with newer staff.

“It can be a very tough school,” said Jennifer Evans, who started at Evergreen five years ago. “You’ve got to be able to take criticism.”