EDITOR’S NOTE: Eleven Idaho schools are launching on an experiment this fall. They are using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools. This is the fourth of a series of stories on the grant recipients.

On Monday, fifth-grader Corina Burr was doing something writers have done since the dawn of the writing assignment. She labored to reach the minimum word count.

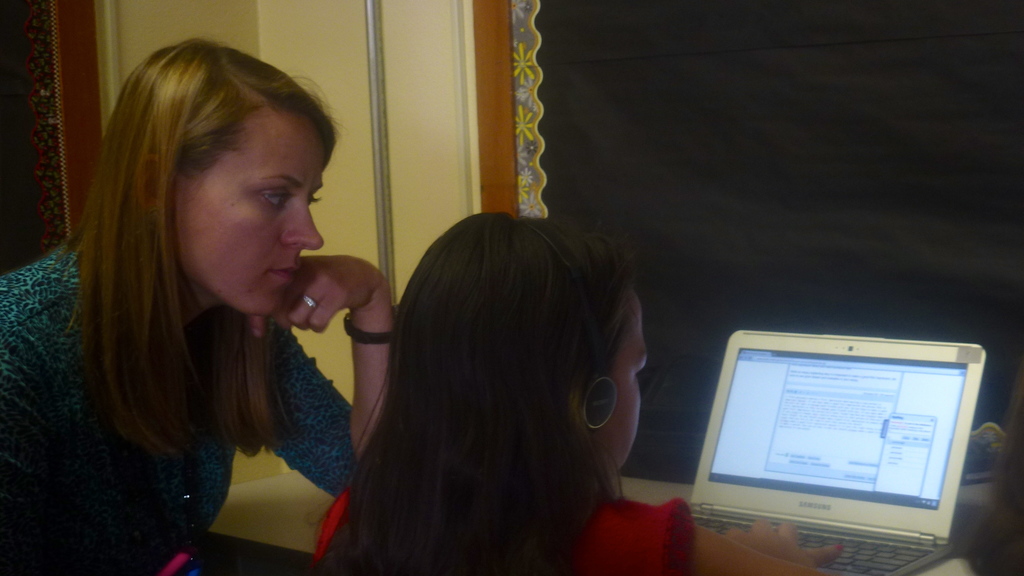

When she hit her 150-word threshold, with encouragement from teacher Kalyn Hochstrat, Burr pressed a button on her school Chromebook and sent the assignment through the WriteToLearn program. The program is designed to provide real-time feedback on word use, grammar and spelling — as well as more nuanced critiques on content.

This was a milestone in Hochstrat’s class at Weiser’s Park Intermediate School — the first writing assignment turned in through WriteToLearn. It figures to be the first of many.

At Park, the whole object of a $54,596 state technology grant is writing. Writing more. And writing more effectively.

The missing ingredient

Park is already performing well academically — a top-rated five-star school, according to state rankings released this summer.

But the school’s fourth- and fifth-graders have historically struggled with writing, a problem that may be rooted in demographics. As the school’s grant application notes, 31 percent of Park’s students are Hispanic, and 14 percent have limited English proficiency.

For years, Park’s scores on the Direct Writing Assessment lagged behind state averages, a performance gap mirrored in the district’s middle school and high school. When the state dropped the DWA in 2008-09, Weiser launched its own writing assessment modeled after the state test.

But the district dropped its efforts in 2012-13 — ironically enough, because of the advent of Idaho Core Standards. These new Common Core math and English language arts standards emphasize critical thinking, and written skills, beginning in third grade.

This prompted Park to embark on another fundamental overhaul — reworking the daily bell schedule to incorporate daily technology lab time, and rethinking the approach to teaching communication skills.

“This is a very big change for us,” said Principal Dave Kerby, who sought, and received, 100 percent backing from the faculty before pursuing the state technology grant.

All of the above

At $54,596, Park received the smallest of the 11 technology pilot grants. The idea, said Kerby, was to come up with a proposal that would improve student performance, “without asking for the world.”

And while some schools, and some state pilot grant recipients, lock into one technology, Weiser’s approach is deliberately broad-based:

- The school is purchasing 30 Chromebooks, small and inexpensive laptops, largely for writing and typing practice.

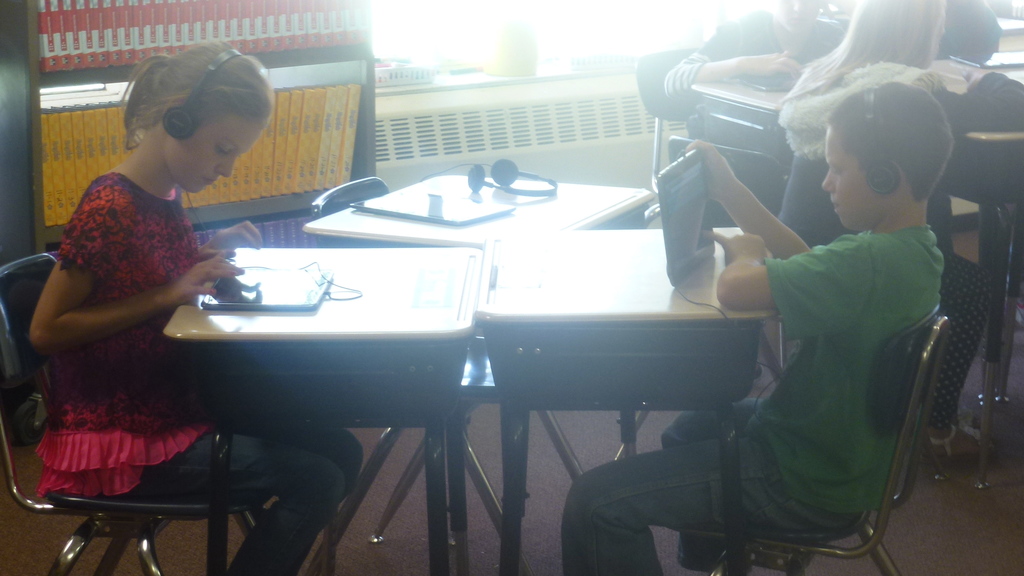

- The school’s 30 new tablets are more conducive for student presentations, Kerby said. The tablets also allow teachers to use multimedia materials. On Monday, Kristin Dickerson’s fifth-grade class used the tablets to listen to a podcast on the water cycle, using headphones to review the material at their own pace; working in near silence, the class of 23 then went over reading material and answered a study question.

- Faculty members will get laptops.

The rest of the grant will go into a host of learning materials — such as the Discovery Education digital “techbooks,” similar to material Dickerson used to teach about the water cycle, and annual fees for the WriteToLearn program.

Starting on the home row

Before students can write to learn, many of them need to learn to type.

Since the school year began on Aug. 26, students have started their daily lab periods with 15 to 20 minutes of typing. For many students, typing is a new skill. Some adhere to the rules during practice — placing their fingertips in the “home row,” as taught in a typing class — but quickly lapse back into hunt-and-peck mode when it’s time to write. And that’s a problem, when Common Core exams are administered on the computer and focused on writing.

“It just all of a sudden became an essential skill to have at this level,” Kerby said.

The school’s grant application sets ambitious goals — in typing and writing alike.

By May 15, the school wants to see students typing 30 words per minute, on average. And the school wants to see each student write at least 20 full-page essays per year.

The writing goal might be unattainable, said Kerby, since it takes time to get student typing skills up to speed. But even if the 20-assignment goal isn’t met, the school is expecting to see students write more.

On average, Kerby said, students used to turn in only three or so papers per year. Papers are time-consuming to grade — and as a former English teacher himself, Kerby sympathizes with the work this creates for teachers. Students, meanwhile, tended to dash off handwritten first drafts of papers, turning them in without reading.

Kerby expects the WriteToLearn program to help teachers and students alike. The WriteToLearn program’s built-in artificial intelligence will catch routine mistakes, making papers easier to grade. WriteToLearn also will allow students to type up to six drafts of an assignment, and turn in a more polished product.

In Hochstrat’s class, that process of writing and rewriting is under way — one assignment at a time.

More stories about the 11 Idaho schools using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools: Learn about Kuna Middle School’s Chromebooks project. Learn about Middleton High School’s laptop pilot. Learn about attempts to reverse achievement gaps at Parma Middle School.