Reading scores tend to improve from fall to spring, as teachers have a full school year to work with young students.

In the fall 2018, 52.5 percent of Idaho kindergarten through third-grade students tested at grade level. By spring 2019, that number was 69.7 percent - an improvement of 17.2 percentage points.

But 13 school districts and one charter school posted improvements of more than 30 percentage points. All 14 started the school year below the state average. By spring, 12 of the 14 came in above the state average.

| District/Charter | City | % Grade level fall 2018 |

% Grade level spring 2019 |

% Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -- STATEWIDE -- | - | 52.5 | 69.7 | 17.2 |

| Aberdeen | Aberdeen | 37.1 | 74.8 | 37.7 |

| Bliss | Bliss | 27.3 | 66.7 | 39.4 |

| Bruneau-Grand View | Bruneau | 37.2 | 76.6 | 39.4 |

| Cambridge | Cambridge | 39.3 | 72.7 | 33.4 |

| Cascade | Cascade | 40.7 | 72.7 | 32 |

| Heritage Academy | Jerome | 27.7 | 59.7 | 32 |

| Kendrick | Kendrick | 43.1 | 76.3 | 33.2 |

| Kootenai | Harrison | 51.2 | 82.5 | 31.3 |

| Marsh Valley | Arimo | 45.8 | 76.5 | 30.7 |

| Notus | Notus | 47.2 | 78.3 | 31.1 |

| Salmon River | Riggins | 45 | 76.2 | 31.2 |

| Soda Springs | Soda Springs | 39 | 74.1 | 35.1 |

| West Bonner County | Priest River | 46.2 | 79 | 32.8 |

| Whitepine | Deary | 41.5 | 79.1 | 37.6 |

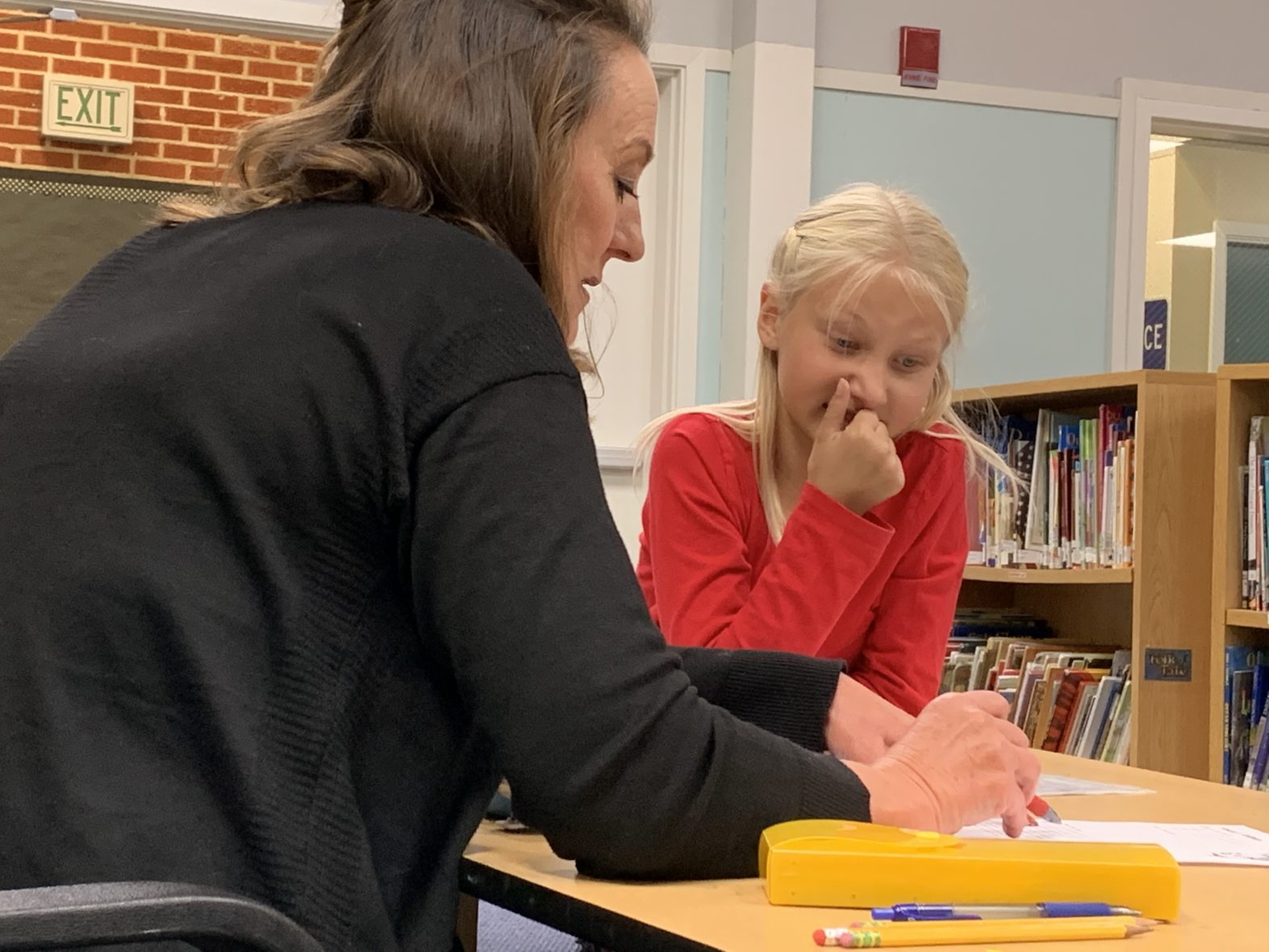

GRAND VIEW — Dixie Amy coaches and cajoles her three students, a fifth-grader and two second-graders. She watches a timer and counts the words as her students read aloud.

She dispenses praise one spritz at a time. When students meet their goals, Amy gives them a quick spray of cheap perfume — so they can go to their next class enveloped in “the smell of good reading.” Even the boys want this reward. “They’ll let me know if I forget.”

For most of the school day, Amy is the receptionist at Grand View Elementary School. But every afternoon, the former paraprofessional leads drills in fluency, or reading speed. She volunteered for the task, and the training for it. At Grand View, reading instruction is an all-hands-on-deck project. Last spring, 80 percent of its K-3 students read at grade level — more than 10 percentage points above the state average.

Some of Idaho’s reading success stories are unfolding in remote, rural schools such as Grand View. Scores are improving significantly. Student growth far exceeds the statewide rate.

Here is how four districts and one charter school are doing it, and what other schools can learn from them.

Cascade: Overcoming budget challenges

In the face of dwindling enrollment, and the decreased state funding that comes with it, this Valley County district is being strategic with the money it has.

Using its $15,000 share of state literacy funding, Cascade hired a part-time reading paraprofessional, a teaching assistant to support the certified, full-time teachers. The paraprofessional works with students who are at grade level, while teachers work with at-risk readers. The idea is to get at-risk students help from the most qualified educators, Principal Joni Stevenson said.

Cascade emphasizes small-group learning. Second-grade teacher Michelle Weirum does almost all of her teaching instruction in small groups, frequently using the Idaho Reading Indicator to track student progress. “You can quickly assess whether they are getting it.”

Cascade is trying to leverage its small size. The district is adopting a new K-12 reading curriculum, hoping it will be a better fit for kids who might spend 13 years in Cascade’s lone school building.

If they stay.

Enrollment fell below 200 this fall. Locals remember a thriving district that once had more than 400 students, said Jeff Blaser, hired as superintendent in 2018. Cascade has been an “underperforming” district, he said, but the improved reading scores could signal a turnaround.

“Right now, our big challenge is building back the trust in the community, that we can get this done.”

Notus: Overcoming demographic challenges

The reading groups spill out from the classrooms into the hallways. At one portable table, four second-graders work independently on computers, completing advanced assignments in grammar and fluency. Down the hallway, at another table, four other students work to catch up on rhyming and letter sounds, using index cards and colored pencils to complete a spelling test.

Instructional assistant Cori Marchbanks works closely with this group.

“I want you practicing here, I want you practicing at home, I want you practicing in the car,” she said. “Come back on Monday, and amaze me.”

In Notus, a small district in rural Canyon County, the school day begins with a 90-minute reading block. As in Bruneau-Grand View, the entire staff helps out, in full classes or small groups.

Notus’ improvement defies some daunting demographics.

Last year, two-thirds of the school’s students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (the state number was 45 percent). Eight percent of students are homeless. Eleven percent of students are English language learners, a growing number. A third of this year’s kindergartners are English language learners, Principal Jen Wright said.

Notus spends its $39,000 in state literacy dollars to hire paraprofessionals. Without them, and without the state funding, the small breakout sessions would fall by the wayside.

“I realize teachers are superstars, but they can’t do it all,” Wright said.

Heritage Academy: Behind-the-scenes improvements

Since June, Heritage has been entangled in an ugly public dispute between charter school advocates and the state’s Public Charter School Commission — after commissioners were recorded making disparaging remarks about the school during an illegal closed-door meeting.

But before this summer of controversy, the Jerome school’s reading scores improved significantly. Heritage’s IRI scores remain below the state average, but that gap shrunk from 25 percentage points to 10.

Unlike many of Idaho’s top-performing and affluent charters, Heritage is a high-poverty school, where 94 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. More than a third of Heritage’s students are Hispanic. More than a fifth of its students are English language learners.

Because of these demographics, many of Heritage’s students lag behind in vocabulary, a stark reality that comes through in IRI results. To combat this, Heritage focuses on phonemic awareness — a fundamental reading skill, linking spoken sounds to the components of words. Teachers can work quickly on letter sounds and phonemic awareness, squeezing in quick instructions during class breaks, kindergarten teacher Kim Radford said.

To some degree, Heritage’s improvements represent a coming of age for the 8-year-old school, administrator Christine Ivie said. Now, staffers can focus on acting on student data, rather than putting out the fires that come with a launch. “There were just program needs that were bigger priorities.”

West Bonner County: ‘We call it the moral imperative’

Kindergartners and first-graders can change quickly. Students who start the school year at grade level can fall behind in a hurry.

So this North Idaho school district moves quickly.

“We group kids right away,” said Susie Luckey, principal at Idaho Hill Elementary School in Oldtown.

Teachers at all three of its elementary schools meet promptly to review test data, grouping students based on strengths and deficiencies. They err on the side of caution; if a student might need extra help, the school provides it. And for as long as it takes. “We don’t let them out of the intervention until they show they are strong and stable,” Luckey said.

West Bonner County posted its biggest improvements in the early grades: from fall to spring, proficiency rates improved by 49 percentage points in kindergarten and 43 percentage points in first grade.

Luckey attributes the success to data collection and coordination.

Like many districts, West Bonner County uses multiple assessments to supplement the IRI. A district literacy cadre meets monthly, and has for several years, to coordinate K-12 English language arts programs.

But for Luckey, a 35-year educator in her 14th year as principal, it begins with a sense of urgency. “We call it the moral imperative.”

Bruneau-Grand View: flexibility and culture change

It takes flexibility to make Grand View Elementary’s program work.

While Dixie Amy works with her three students, perfume bottle at the ready, teacher Lexie Malika sits on a carpet in another classroom, reading to a small group. But she is supervising 37 students — every Grand View student who is at grade level.

It is something of an exercise in crowd control. But it’s necessary, Superintendent Ryan Cantrell says, to allow other staffers to work with small groups.

Cantrell preaches teamwork and holds up teacher Maya Davis as an example. This year’s group of Grand View third-graders has struggled in previous years. Davis volunteered to move to the third grade. She says it was tough to give up her old job, teaching kindergarten, but she taught many of her new students three years ago, easing the transition. “From day one, our relationships were already built.”

Success comes down to staffing. And for small, remote schools, that’s where recruiting and retention issues come to a head. It’s relatively easy to hang on to a reading paraprofessional — Bruneau-Grand View uses much of its $25,000 in literacy money on paraprofessionals, and Cantrell said the district hires locally. Keeping teachers is another matter. Teacher turnover is down to 14 percent, after hovering between 30 and 40 percent for several years.

Salary is inevitably a factor, and Cantrell knows he can’t compete with districts in the nearby Treasure Valley, which offer higher wages. But Bruneau-Grand View’s turnover is also a function of culture. After the district landed on the state’s list of lowest-performing schools, Cantrell knew he had to change the teaching culture, undergoing the same reexamination that is now beginning in Cascade.

“It was a three-year shift … to really shift that mindset,” he said. “And not everybody stayed on the bus.”

Idaho’s reading challenge: This series at a glance

Day One

Reading realities: Idaho plays catchup

Following the dollars, defining success

Day Two

What’s working? School success stories

Idaho’s daunting demographic hurdles

Day Three

Testing kids, and seeking answers

Early education expands across Idaho

Day Four

Reading policy and reading politics