From the North Idaho college town of Moscow to the small southeast Idaho town of Dayton, 11 Idaho schools are only a few months into their technology pilot projects.

But in January, when lawmakers from around the state convene in Boise, they may have to decide whether they want to put more money into more pilots.

Lawmakers will have some anecdotal evidence from the field, but test results may be scarce. Lawmakers will, however, have a $3 million funding request from Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Luna — money that could be used for additional pilots.

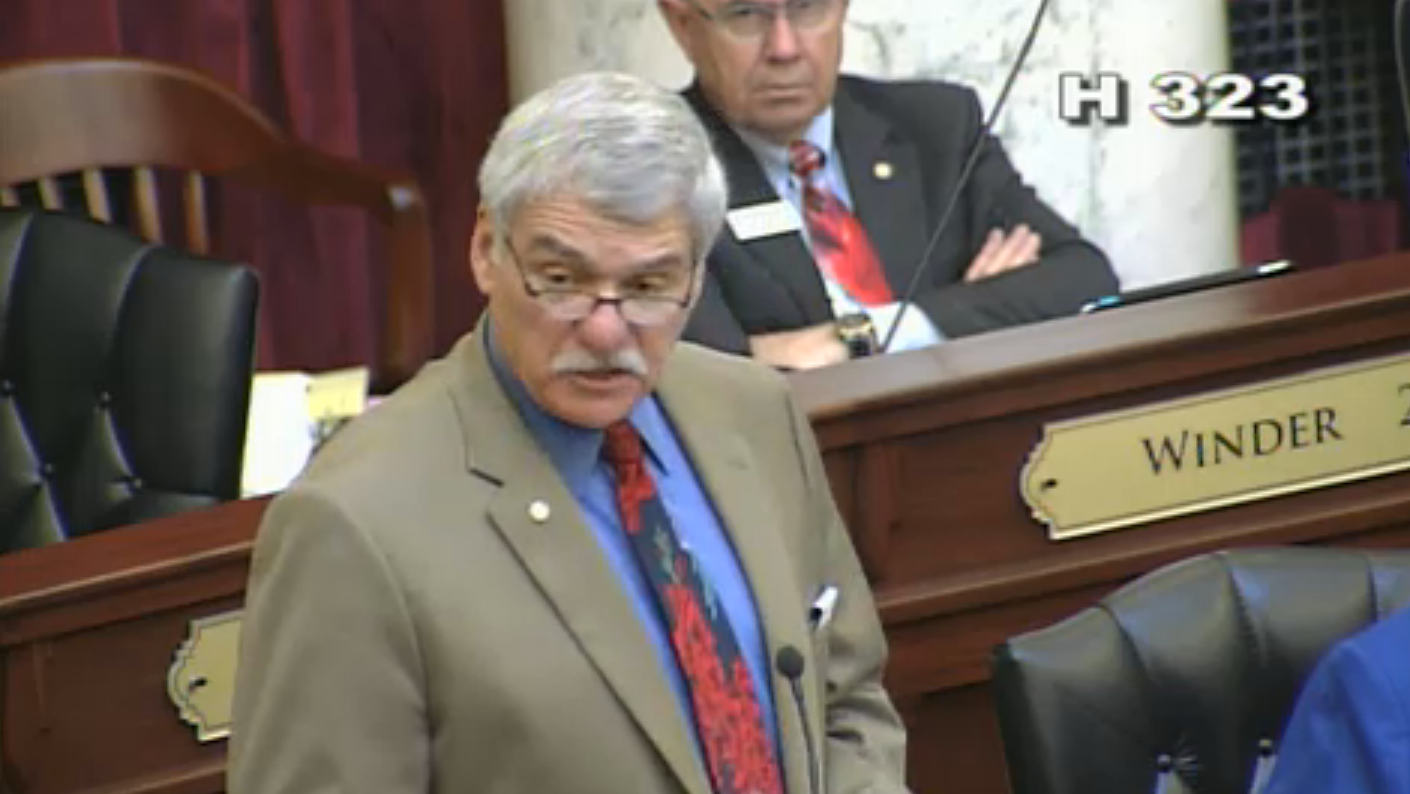

Of course, that’s just a request. Luna says $3 million might not be enough to satisfy lawmakers who want to fund a “considerable” classroom technology upgrade. A $3 million request would not be a “slam dunk,” Senate Education Committee Chairman John Goedde said, since some lawmakers may not be convinced that a second round of pilots is necessary.

And then there’s Gov. Butch Otter. On Jan. 6, Otter presents his own budget proposal — one that might or might not mirror Luna’s request to boost K-12 spending by 5.4 percent.

Local approaches

The 11 schools that are sharing $3 million in grants seem to share no other common thread.

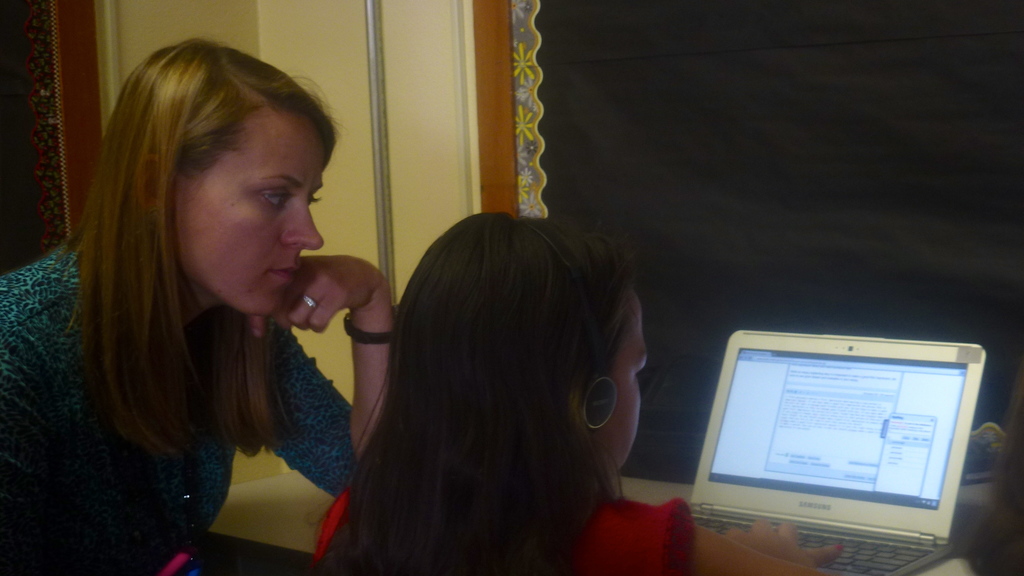

They are using very different devices, from laptops in Sugar City High School to interactive whiteboards in Moscow Middle School. In other schools, iPad tablets or small Chromebooks are the device of choice.

They have very different objectives. Middleton High School wants to give students skills for life after graduation, while Weiser’s Park Intermediate School wants to improve reading skills. At McCall-Donnelly High School, a five-star school in recent state rankings, iPads are seen as a tool to make studying and note-taking more convenient. Meanwhile, administrators want to bridge an achievement gap at Parma Middle School, a two-star school sandwiched between a high-performing grade school and high school.

The pricetags also vary widely, from an $891,200 Chromebook project in Kuna Middle School to the $54,596 Park project.

In the aftermath of Proposition 3 — one of Luna’s voter-rejected Students Come First laws, which would have provided every Idaho high school student a laptop — the pilot program encouraged local school officials to brainstorm.

“They’re all doing different things because they locally determined what their needs are,” said Idaho Education Association President Penni Cyr, a member of the state Education Department team that reviewed grant applications in June. “I hope we keep that in mind.”

The concept of local control was not lost on Otter’s education reform task force. The group — which included Luna, Goedde, Cyr and 28 other education stakeholders — treaded carefully around the technology question. They called for uniform broadband and WiFi in the schools. They said every student should be equipped with a “technology device,” but deliberately skirted details.

Works in progress

It’s been a rapid rollout at the 11 pilot schools. The schools got word of their grants on July 1, less than two months before the start of the 2013-14 school year. Some have had to work through a variety of hiccups — acquiring charging stations, installing Internet security software, waiting for the state to upgrade WiFi service, training students and parents on how the devices will be used in class.

Luna says he is “very impressed” with what he is seeing so far: students in the pilot schools are more engaged and learning at their own pace. But he says it’s too early to know which pilot schools are performing best.

Goedde isn’t expecting immediate answers either.

“In many cases it’s going to take a couple of years to see how things are really working.”

But the 2014 Legislature could still have to make a $3 million technology decision.

Future funding

Luna is seeking the $3 million, but said it would have be “premature” to request more, just a few weeks into the pilot program. His budget request incorporates all 20 recommendations from the task force — including first steps to create a teacher salary ladder and reverse recession-era cuts to school operating budgets — but includes no additional money for classroom technology.

Luna says he is hearing from some lawmakers who want to put more money into technology. And from Luna’s perspective, that would mean putting more money into the K-12 budget. He doesn’t want lawmakers to siphon funding from any of the task force recommendations; he thinks lawmakers should support and fund the entire package.

If lawmakers fund a second round of technology pilots, they won’t lack for bidders. This year, the state received 81 requests for a total of $19.5 million — and probably was forced to turn down some promising approaches. “I’m sure we missed some things that could be embraced,” said Goedde.

Ultimately, funding pilot programs are a double-edged sword, he said. Pilots allow schools to experiment with approaches that can be replicated elsewhere. But the grants give some schools a funding boost, in a state where the Constitution mandates a uniform public school system.

Luna sees it differently. The long-term goal of the pilot program is to come up with plans that will bring technology into every classroom. “It‘s not to create winners and losers.”

Here are in-depth stories on the state’s 11 technology pilot schools:

- A schoolwide Chromebooks project at Kuna Middle School.

- A career-oriented laptop pilot at Middleton High School.

- An attempt to reverse achievement gaps at Parma Middle School.

- A writing emphasis at Weiser’s Park Intermediate School.

- A collaborative learning effort at Meridian’s Discovery Elementary School.

- A student-led iPad rollout at McCall-Donnelly High School.

- An effort to bridge geographic gaps at the Idaho Distance Education Academy.

- A Proposition 3 lookalike at Sugar Salem High School.

- Teachers and students team up to rollout iPads at Dayton’s Beutler Middle School.

- A big-screen vision at Moscow Middle School.

- A K-12 approach at Meridian’s Compass Public Charter School.