When dual credit works, it works for students such as Daphne Dryden.

She will graduate from Coeur d’Alene High School next year with an associate’s degree from her hometown North Idaho College. She says it’s a time management challenge — this year, she’ll have to balance nine college-level classes with high school coursework.

Eventually, dual credit will save Daphne time and money. When she enrolls at the University of Idaho next fall, she’ll be two or three years away from getting a bachelor’s degree in business, with a minor in French. “I definitely want to get that done pretty soon, so I can get out in the work force.”

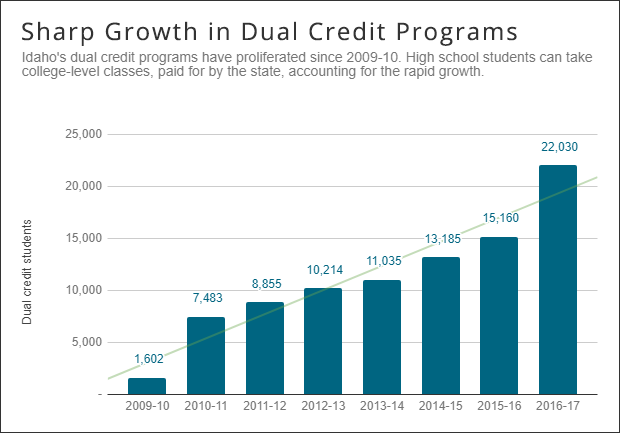

By taking dual credit classes at the state’s expense, Daphne is on a college fast track. The program works well for high achievers — students already hard-wired for college.

But is Idaho doing enough for other students? Does Idaho have a plan to get more students into the postsecondary pipeline, pursuing a college degree or a professional certificate?

That’s the premise of Idaho’s “60 percent goal.” State leaders want 60 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds to complete some postsecondary program. The 2015 number is mired at 42 percent.

Education and political leaders say it will take two things to move that number.

More time.

And more money.

Building the counseling pipeline

Kari Hynes is part of Idaho’s new class of school counselors. She moved from NIC to Coeur d’Alene High School a year ago — hired with Coeur d’Alene’s share of a $5 million line item for college and career counselors.

Hynes quickly got a sense of the challenge facing her. When she surveyed ninth-graders last year, 91 percent of them said they planned to go on to college. But only 60 percent of 12th-graders said they were college-bound.

What happens along the way? “I think life is happening,” Hynes said.

The college sticker price leaves some students overwhelmed. Other students, especially first-generation college students, struggle because they don’t have a family support system.

By adding counselors, Idaho is trying to build up the support system, within the walls of the high school. The new hires have plenty of work to do: helping high school students select wisely from a wide array of dual-credit and career-technical course options, and helping seniors work on college applications and financial aid forms.

The biggest beneficiaries are students with middle-of-the-pack transcripts, “the kids who have a two point something,” said Liz Clark, a counselor in the Blaine County schools. In the past, these students might have gotten little more than drive-by advice. Now, they receive more attention.

But even with more time and a more manageable workload, a high school counselor still shows up only at the back end of the process. Educators want to start the process sooner.

In Coeur d’Alene, counselors are starting to work with eighth-graders on a career portfolio. The goal is to get junior high school students considering their life options — be it two- or four-year college or a career-technical certificate — and how junior and senior high school can help them prepare.

“We have them look at it every year, because it changes,” Hynes said. “They’re teenagers.”

Idaho can’t afford to wait, University of Idaho President Chuck Staben said. If the state wants to improve its postsecondary graduation numbers, the state needs to start reaching out to kids and parents by junior high school.

“I often say students begin to drop out of college in the eighth grade, because their aspirations change,” Staben said.

The nontraditional route

About 277,700 Idahoans have some college education, but no degree.

They get no benefit from state initiatives aimed at high school students. These 277,700 Idahoans could be critical to meeting the 60 percent goal.

Rep. Wendy Horman says the state has to make it easier for nontraditional students to earn a degree or certificate. She speaks from experience; she earned her bachelor’s degree at 43.

“I know how difficult it was,” said Horman, R-Idaho Falls, a member of the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee, the legislative panel that writes budgets for K-12, higher education and other state agencies.

Helping nontraditional students could come at a cost — an additional $3 million a year.

For the past two legislative sessions, Gov. Butch Otter has pushed for an “adult completer” scholarship to provide nontraditional students up to $3,000 a year to return to school.

The scholarship bill hasn’t gone anywhere. It received a boost earlier this year, when Otter’s higher education task force endorsed the adult completer scholarship.

Critics such as Wayne Hoffman, executive director of the Idaho Freedom Foundation, a conservative lobbying group, have said the scholarship rewards college dropouts. Boise State University President Bob Kustra doesn’t buy the argument. He says he routinely comes across students who simply had to leave college to go to work to support a young family.

“I don’t see any reason why you wouldn’t want to give a person a second chance,” Kustra said.

A college without a campus

As co-chair of Otter’s higher education task force, Boise business executive Bob Lokken says Idaho has to confront some hard truths.

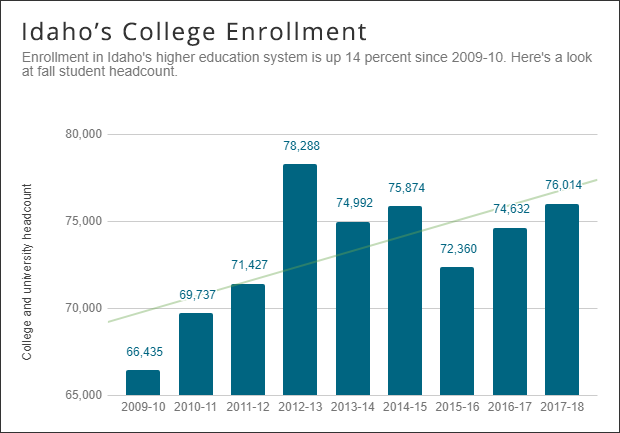

The “60 percent” postsecondary completion goal has been around for seven years, and Idaho is far from hitting the mark. College enrollment increased earlier in the decade — but that might have more to do with the recession and a bad job market, and might have had nothing to do with state policy.

And Idaho’s existing education system just might not be built to meet the 60 percent goal. There isn’t room on the campuses to accommodate an additional 40,000 students, and some Idahoans simply cannot relocate to a college town or fit a traditional class schedule into their lives.

And Idaho’s existing education system just might not be built to meet the 60 percent goal. There isn’t room on the campuses to accommodate an additional 40,000 students, and some Idahoans simply cannot relocate to a college town or fit a traditional class schedule into their lives.

“You have to build something with a very different structure and architecture,” Lokken said. “We were trying to build a system for the rest of the people.”

From this grew the task force’s idea for a makeover: a “digital campus” that pushes low-cost classes into public libraries and other portals across Idaho.

In theory, the digital campus could address some problems that have long thwarted Idaho.

It could bring postsecondary classes to underserved rural Idaho — where many high school graduates and their parents question the value of higher education. It could make college more accessible for nontraditional students who are juggling work and family obligations. It could stem the rising cost of college — and combat affordability concerns.

Like all of the recommendations from the higher ed task force, this idea drew unanimous support from the 36 education leaders, business executives and politicians serving at Otter’s behest. But unanimity does not equate to universal enthusiasm.

Rep. Ilana Rubel, D-Boise, says a digital campus could play a role in getting more students into the system. But while her task force colleagues are expecting a game changer, Rubel is skeptical. After all, rural Idahoans can already access online college courses from a plethora of vendors. “It’s there now and it hasn’t changed the game.”

Kustra is bullish on digital learning: Boise State already offers 30 online degrees and certificates, and he says the university should do more.

But after 15 years in charge of the state’s largest university, the retiring Kustra is skeptical about the Legislature’s resolve. He’s hoping for an “a-ha moment,” when legislators commit to investing in postsecondary education, because a digital campus will require a large upfront commitment.

“There’s little evidence in the past that we have a Legislature that is willing to jump in and do that,” he said.

A long and disruptive process

It’s unclear what Otter will do about the digital campus — or any of the task force’s other ideas. The retiring three-term governor hinted at changes to the higher ed system in a speech last week. But he is not talking about details until January, when he delivers his 12th and final State of the State address to the 2018 Legislature.

Otter will have one last chance to make a mark on Idaho’s postsecondary system — and address a 60 percent goal unveiled at the end of his first term as governor.

But after seven years, the road to the 60 percent mark remains an eight-year journey. Much of the followup work will fall to Idaho’s next governor, several new university presidents and future legislators. The digital campus will take years to make a reality; the State Board doesn’t yet have an estimate on startup costs. The task force report is rife with several other long-term goals.

But Idaho doesn’t have much choice, said State Board President Linda Clark, the task force’s co-chair. If the state keeps doing the same things, it will get the same results. Change isn’t easy, but it is necessary.

“It’s going to be a disruptive process, but it’s a process, and that takes some time,” she said.

About this series

In “Life After High School: Options And Outcomes for Idaho Graduates,” Idaho Education News takes an in-depth look at the state’s “60 percent goal.” Why is Idaho still struggling to convince high school graduates to continue their education? We look at the policies that shape this issue — and talk to students about their plans and the personal decisions.

Here’s the series at a glance:

Day One. After five years and $100 million, Idaho remains far from its ’60 percent goal’

Day Two. A defining decision: Five high school students talk about their plans

Day Three. As Idaho tries to sell the value of college, the sticker price keeps rising

Day Four. It will take even more time and money to reach Idaho’s ’60 percent goal’