(EDITOR’S NOTE: Over the next year, Idaho Education News will provide in-depth, ongoing coverage of the challenges facing higher education during the coronavirus pandemic. Here’s our latest installment in this project.)

Lawmakers turned up the fiscal pressure on higher education this year — on the basis of anecdotes and narratives.

The Legislature finally passed a higher education budget this week, cutting $2.5 million in the name of stamping out campus indoctrination.

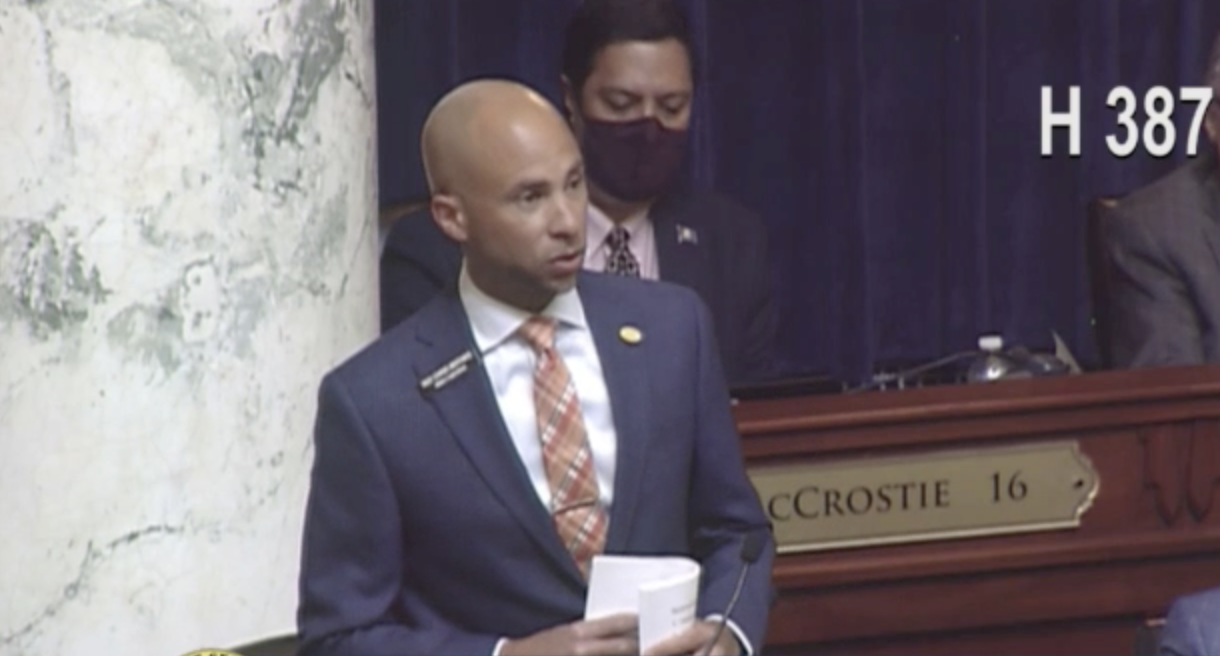

But before the House passed the budget Monday, on a surprisingly comfortable 49-20 vote, Rep. Chris Mathias spoke emotionally, from his life experience as a Black man, and from his professional training as former chief academic officer for the State Board of Education. The debate, he said, was only technically about dollars. “What I feel, however, that we’re really debating is the question of how scared should we be of social justice and critical race theory.”

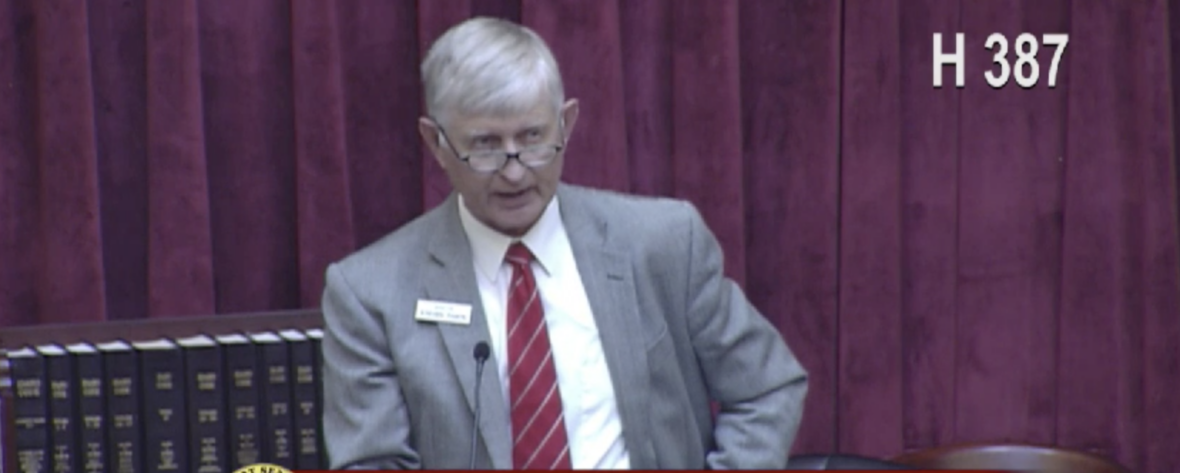

On Tuesday, before the Senate passed the same budget on a 26-8 vote, Senate Education Committee Chairman Steven Thayn discussed his own experiences in college — and pushed back against the idea that students aren’t ostracized over their beliefs. “If you’re a conservative white male Christian in the last 40 years in the United States, like I was, I can tell you that it has been going on.”

Narratives are powerful, but anecdotal. They’re not a good foundation for a budget. And next year’s higher education budget could directly affect the courses available to college and university students, and faculty and staffing at the four-year schools.

But let’s start with this week’s floor debates, since they say a lot about the 2021 session.

What Mathias said

His voice quaking with emotion, Mathias, D-Boise, recalled attending Boise State University on the GI Bill. “That place provided opportunities I’d never seen in my life. It changed my life.”

Then he defended the embattled Boise State as an alumnus, and said the state’s appreciation for its higher education institutions was reaching a point that is “dangerously low.”

And then Mathias took on the catchphrases that have been thrown around freely and casually this session. Social justice, he said, is simply the pursuit of fairness in societal settings. Critical race theory, he said, recognizes deep-seated — yet ultimately fixable — institutional biases that have existed for centuries. “People of color always come out on the losing end,” said Mathias, again fighting back his emotions. “Always. And I don’t think it’s unfair to acknowledge it.”

Discussing social justice and critical race theory can be uncomfortable, Mathias said during debate. That was certainly the case Monday. Three conservative Republicans — Ron Nate of Rexburg, Heather Scott of Blanchard and Tammy Nichols of Middleton — objected to Mathias’ debate. They criticized Mathias for bringing up critical race theory, even though this topic has been a focal point in the conservative backlash against higher education. The objections caused House Speaker Scott Bedke to pause the debate briefly.

After the five-minute cooling-off period, Mathias appealed to lawmakers to pass the budgets, cuts and all, and fund the four-year schools. “They are doing their absolute best with almost no help from us.”

Mathias voted for the budget.

(Click here to watch Mathias’ debate.)

What Thayn said

After Senate Democrats took turns criticizing the rewritten higher ed budget, dismissing the notion of an agenda of indoctrination, Thayn did not hide his exasperation.

“I’ve heard enough,” said the Emmett Republican.

Then Thayn related his own experience as a Boise State student, but not in the glowing terms Mathias used a day earlier.

Thayn said he took a Boise State philosophy class in 1978. He said he sat silently while the professor said man has never been able to define the nature of God. Following that line of reasoning, the professor challenged the premise of a nation built on God-given rights. Thayn said he couldn’t stay silent, and told the professor that the Founding Fathers were able to define the nature of God, and build a government accordingly. “He had absolutely nothing to say, but I got my F.” Thayn also said his classmates laughed at him and ridiculed him several times during the semester.

Thayn also related another anecdote — from a Hispanic Statehouse aide, who said one of her Boise State professors said she was “too brown to succeed in Idaho.”

Thayn went on to say that he supports Idaho’s current group of college and university presidents, saying he has faith that they will fix the problems on their campuses. But he also said he was comfortable cutting the budget. “Every once in a while, we need to step back and say, ‘Let’s make sure we’re treating people fairly.’”

Thayn voted for the budget.

(Click here to watch Thayn’s debate.)

What we need to hear next: data

The genius of a citizen’s legislature is that representatives can come from any perspective, any background. It allows for a mix of life experiences and life stories. So there’s room for 105 legislators — and these two legislators in particular — to view the higher education system from very different vantage points.

There’s also room in a vast higher education system for two people, such as Mathias and Thayn, to have two very different experiences on campus.

But this year’s higher education debate has been driven almost exclusively by personal stories, firsthand or secondhand. There’s a shortage of hard evidence and hard data. Considering that the higher education system is a data-disseminating machine — churning out numbers on enrollment, demographics, retention and graduation rates and more — the lack of data in the social justice/freedom of expression arena is conspicuous.

As new State Board of Education President Kurt Liebich noted last month, the State Board’s first job is to quantify the extent of the problem. Student complaints could be a good place to start; as Boise Democratic Sen. Melissa Wintrow noted after Thayn’s debate, the colleges and universities have procedures to investigate the very problems Thayn brought up.

But data gathering has its limits.

“No measure of social justice education is perfect,” the Idaho Freedom Foundation noted in white papers criticizing social justice programs at Boise State and the University of Idaho. But that hasn’t stopped the foundation from saying the cost of campus social justice programs comes to $20 million a year — without providing specifics. (The foundation has not responded to repeated inquiries from Idaho Education News.)

After four months of lobbying and lamenting from the foundation, and legislative allies such as Nate, lawmakers agreed to cut the higher education budget. We don’t know all the details here either, but the cuts will affect staffing. Positions might be cut or left vacant. Students, in turn, might have a tougher time finding the core classes they need to graduate.

Idaho colleges and universities get their operating money from two sources: state tax dollars, and tuition and fees. Factoring in the cuts in the new budget bill, higher ed will receive a modest 2 percent increase in taxpayer support. And the four-year schools have already agreed to freeze in-state undergraduate tuition for a second year.

Those are hard, cold realities. The 2021 Legislature didn’t make the job any easier.

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for it every Thursday.

More in-depth higher education coverage

Aug. 6: A pandemic makes old problems worse for Idaho higher education

Aug. 12: Idaho campuses prepare to reopen, but will students show up?

Aug. 24: Across the state, campuses open for an uncertain new year

Sept. 24: The feds’ coronavirus aid fills some gaps, but only some

Oct. 8: Boise State faces a financial reckoning

Nov. 3: New Boise State program seeks to guide students through gap year

Nov. 12: In a pandemic, colleges struggle even more to attract Idaho graduates

Dec. 3: One semester down, a tougher semester ahead

Jan. 5: Instead of going on, Idaho high school graduates stayed home

Jan. 28: Previewing Idaho’s next higher education budget battle

Feb. 18: The day the 60 percent goal almost died

Feb. 25: The higher education Statehouse showdown starts next week