Tennessee has taken an old debate to a new level.

A Republican lieutenant governor and Republican House speaker have assembled a committee to study the question of refusing federal money for K-12 — up to $1.8 billion in all, according to Chalkbeat Tennessee. The committee met earlier this week, and quickly encountered the complexities of opting out. But Tennessee’s committee is significant in and of itself, just because it exists.

“Tennessee has gone further than any state before toward refusing (federal) money,” Education Week reporter Libby Stanford wrote last week.

Tennessee is escalating a debate that began, it seemed, the day the feds started putting money into education. Is the money worth the red tape — and the top-down dictates — that inevitably come with it?

It’s an evergreen topic in Idaho, albeit on the periphery.

Behind the scenes, state superintendent Debbie Critchfield and her senior staff have been weighing the pros and cons of a staggering, multimillion-dollar opt-out. Her State Department of Education is in data-gathering mode — and is declining to go public with what it has, spokesman Scott Graf said Thursday, because the work is preliminary. Graf did say, however, that the department’s documents make no recommendations on opting out.

But late Wednesday afternoon, the department did release a one-pager to Idaho EdNews — a breakdown of Idaho’s cut of federal K-12 funding. The bottom line for 2022-23: nearly $525.2 million.

Almost half of the money comes from federal COVID-19 relief funds; this one-time money will eventually come off the books. But the rest of the money quantifies the Uncle Sam’s far-reaching role in Idaho education:

- Child nutrition: $101.7 million, serving more than 280,000 students.

- “Title” programs: $90.7 million. This is a catchall encompassing a variety of federal programs serving at-risk students, English language learners and homeless, migratory or neglected students, or 130,000 students in all.

- Special education: $64.7 million, serving 36,000 students.

- Student engagement and safety: $11.4 million.

“Is the state ready to supplant the federal dollars, to that amount?” Critchfield said in an interview Wednesday.

Critchfield said her department’s in-house data hasn’t changed her mind yet. The pros and cons remain.

Opting out could buy a state some autonomy — in areas such as testing, which give Critchfield chronic heartburn. “We should be driving our own ship here.”

But opting out doesn’t eliminate all federal mandates. The feds’ “maintenance of effort” requirement would remain intact, dictating stable or increased special education spending. That means Idaho — already struggling with a $66 million special education budget gap, even with the feds’ support — would have to pay all the bills on its own.

“We can’t not provide these services to our most vulnerable students,” said Ryan Cantrell, the SDE’s chief deputy superintendent.

While the SDE continues its internal review of opting out, the question continues to pop up in other forums — like a regional school superintendents’ meeting in eastern Idaho on Nov. 1. Hearing local administrators complain about the bureaucratic hoops they need to jump through to use federal dollars, state Rep. Wendy Horman floated the idea of simply opting out.

The co-chair of the Legislature’s powerful budget-writing Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee, Horman insists she isn’t proposing an opt-out, and doesn’t know of any opt-out bills in the works. However, she added, “I have certainly answered a lot of questions from my colleagues.”

Horman, R-Idaho Falls, is a go-to source around the Statehouse for K-12 budget intel, having written spending bills for schools for years. And she has a variety of concerns about using federal dollars to supplement the state’s K-12 budget.

Philosophically, she is concerned that the feds use their money to influence curriculum (even though those decisions are made strictly at the local level) and secure restroom accommodations for transgender students (even though the 2023 Legislature passed a law addressing this topic). Her concerns are also pragmatic, as the national debt continues to spiral, and Congress continually struggles with the basic function of passing spending bills.

“I think it’s a fair question at this point to ask if state funding or federal funding is more reliable,” she said this week.

Geoffrey Thomas knows federal money comes with strings attached. But he also knows how hard it is to walk away from it.

In 2015, the Madison School District superintendent found himself in the middle of a statewide dustup when he tried to opt out of tests aligned with Common Core academic standards. The move jeopardized $11.6 million in federal money statewide — and earned Thomas a phone call from then-Gov. Butch Otter.

Thomas relented, and Madison administered the test.

Madison’s trustees also found it was no easier to opt out of federal money at the district level.

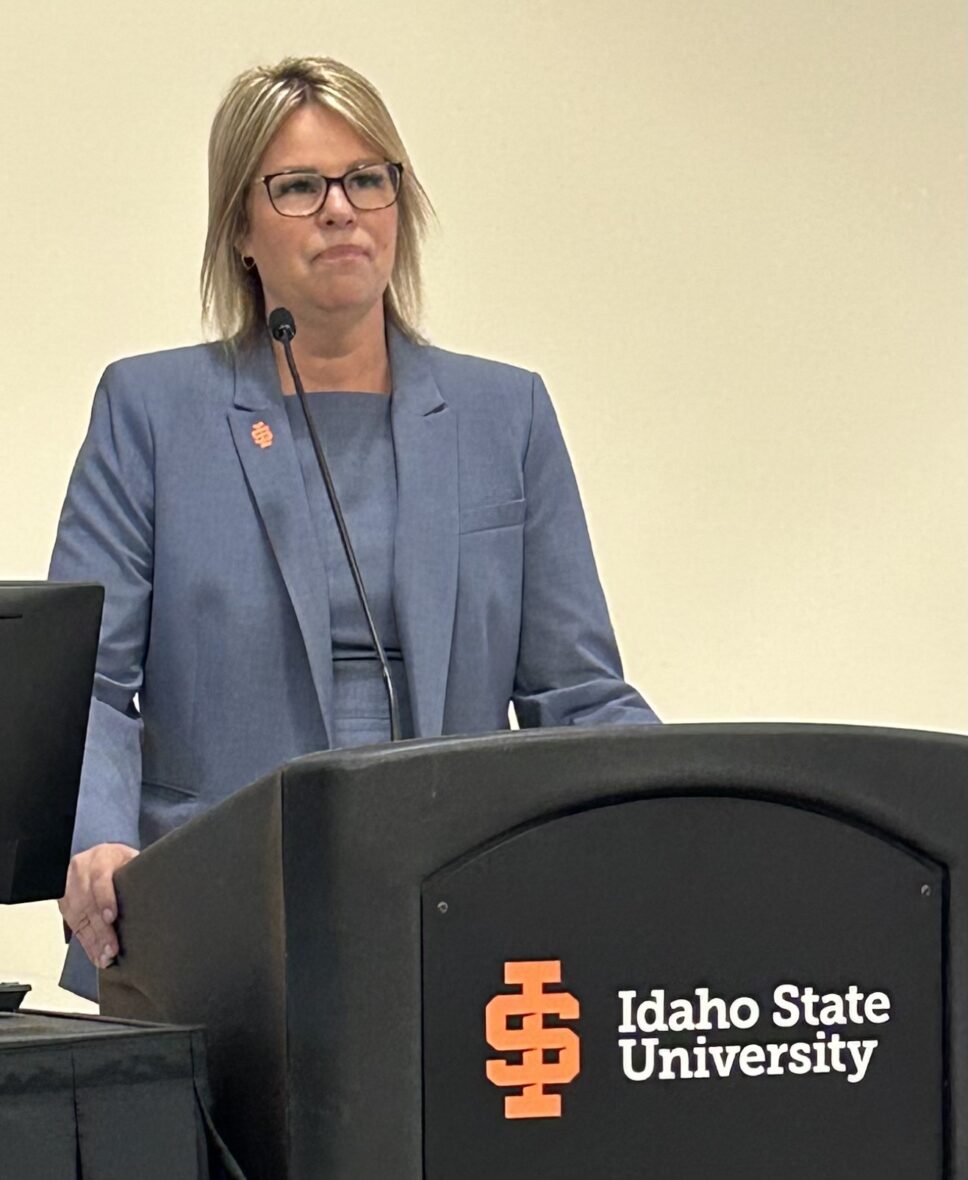

“We talked about that, but we couldn’t financially swing it,” said Thomas, now an assistant professor of education at Idaho State University. “We needed that federal spending.”

Need is a powerful thing to overcome, which is why Thomas and others don’t expect much to come from the Tennessee committee.

Opting out of federal money would commit a state to spend a huge sum of money just to keep existing education programs running — as opposed to launching a new initiative or doubling down on a popular and successful program. If a state can save money by skirting federal red tape, they might not realize these savings for years. Meanwhile, this state will be on the hook, year after year, to replace foregone federal dollars.

“And people are notoriously short-sighted,” Thomas said.

True. But politicians have a keen eye for the opportunity of the moment. And as immediate-gratification soundbites go, it’s hard to beat something like, “Get the feds out of our schools.”

Which is why, regardless of what happens in Tennessee, this age-old unresolved debate will never go away.

Kevin Richert writes a weekly analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for his stories each Thursday.