As Idaho’s coronavirus case numbers surge again, vaccination numbers continue to lag.

And vaccination rates are lowest among young people — just weeks before students are due to return to schools and college campuses.

This puts health officials and education leaders in a bind.

They say vaccines offer the best opportunity to provide in-person learning, activities and athletic events, while preventing community outbreaks.

But they cannot mandate anything.

They can only encourage vaccinations — and try to make the vaccines as accessible as possible.

And hope it all works, as the pandemic enters another sobering stage.

The numbers are changing — and they’re all grim

Department of Health and Welfare Director Dave Jeppesen opened a Tuesday news conference with a troubling headline: Every coronavirus metric in Idaho is “headed in the wrong direction.”

The seven-day rolling average of new cases is rising. A higher percentage of tests is coming back positive. COVID-related hospitalizations are increasing. ICU admissions have doubled since July 1.

That was Tuesday. On Wednesday, Idaho added another 325 coronavirus cases, the largest one-day spike since April 14.

It’s not clear how many of these cases stem from the new and more contagious delta variant. The state has pinpointed just nine delta variant cases — but since the state’s lab capacity is limited, that number is almost certainly low.

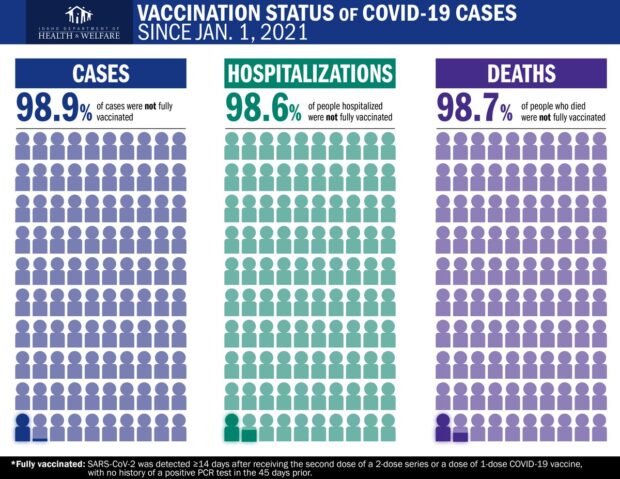

One thing hasn’t changed since January, and the onset of the vaccines. Nearly every coronavirus case, hospitalization or death, involves someone who didn’t get the jab. “This has really become a pandemic for those that are unvaccinated,” Jeppesen said.

The upside? “What we know is that people are receiving protection from the virus through the vaccine, and the vaccines are keeping people from getting sick, keeping people out of the hospital, and saving lives,” said Elke Shaw-Tulloch, Health and Welfare’s public health administrator.

That is, if people get the vaccine.

Now, for more grim numbers.

Only 45 percent of eligible Idahoans are fully vaccinated, compared to 57 percent nationally.

When it comes to students, Idaho’s vaccination rates are even worse: just 15 percent for 12- to 15-year-olds, 25 percent for 16- and 17-year-olds and 32 percent for 18- to 24-year-olds.

Idaho’s low student vaccination rates mirror the national trends. But the state’s dismal numbers hide a stark geographic split. In Idaho’s Central Health District — Ada, Boise, Elmore and Valley counties — vaccination rates run at least 10 percentage points higher than every other health district in Idaho.

If the coronavirus has become a pandemic of the unvaccinated, as Jeppesen said, the state’s numbers suggest that a vast majority of students, across a wide swath of rural Idaho, will head to school unvaccinated.

A race to vaccinate, and persuade skeptical Idahoans

And that’s one reason health experts are worried. Even if the coronavirus poses less of a health risk to children — as the data strongly suggests — an outbreak could spread from the school into the community. If more kids are vaccinated, that could provide a level of protection for people who cannot get the vaccine for health reasons, or children under age 12, who aren’t eligible for the vaccine.

If eligible students are going to get vaccinated before the start of the school year, now is the time, Shaw-Tulloch said Tuesday. This would give students time to get two doses of the Pfizer vaccine, three weeks apart, and have full protection before the first day of school.

The Boise School District has been trying to get out ahead of the virus, hosting five mobile vaccination clinics at junior high schools earlier this month. District spokesman Dan Hollar wasn’t sure how many students showed up for the clinics.

But as public K-12 school leaders brace for the start of the school year, and the unknown impacts of the delta variant, their options are somewhat limited. They cannot mandate vaccinations — the COVID-19 vaccine isn’t on the state’s list of recommended vaccines, and parents can easily opt their kids out of any vaccine anyway, simply by turning in a note.

K-12 and health officials have a few tools. They can make vaccinations more convenient and accessible, through mobile clinics. And they have the power of the bully pulpit. Health and Welfare is using blogs and social media to talk up the importance of vaccines, and will double down with PSAs this week and an ad campaign this summer, spokeswoman Niki Forbing-Orr said.

Colleges emphasize convenience — and appeal to a sense of community

Boise State University talked about a campuswide vaccine mandate earlier this year. But not for long.

“I think we thought about it for half a second,” Chief of Staff Alicia Estey said Wednesday. “I think we just had to say, ‘We’re not doing this.’”

Of course, that brief discussion occurred before Gov. Brad Little made the issue moot. His April executive order banning “vaccine passports” prohibits any vaccine mandates on public college and university campuses.

The state’s private schools — The College of Idaho, Northwest Nazarene University and Brigham Young University-Idaho — won’t require vaccines either. But the C of I will exert some financial pressure: If students don’t get a vaccine or a college-approved religious or medical exemption, they will have to submit to weekly COVID-19 tests, at a cost of $89.

With vaccine mandates off the table, the colleges and universities are emphasizing access — and messaging.

Boise State will run a vaccination clinic before fall classes, providing the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, the one-shot option students prefer. That’s a complicated decision, Estey said, amid reports that the J&J vaccine provides less protection from the delta variant.

Idaho State University will provide rotating clinics across campus during the first week of fall semester, setting up shop wherever students live or take classes. “Not all students cross one central location,” assistant vice president and dean of students Craig Chatriand said.

Still, the universities are attempting to appeal to a sense of community. The University of Idaho’s fall messaging will rely heavily on students, and a peer-to-peer approach to encouraging vaccinations, health promotion director Emily Tuschhoff said. That strategy will be geared somewhat toward rural students, who have spent their summer in Idaho communities with lagging vaccination rates.

The prevailing message holds out the prospect of a normal campus experience. Face-to-face classes. A full slate of campus events. Sporting events and full student sessions.

In 2021, that’s the hope. But in 2021, there aren’t any guarantees.

“We may have to roll things back,” Estey said. “We may have to reinstitute a mask mandate.”

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for it every Thursday.