It sounds so simple.

Just cut the strings and send the state’s tax money to the schools. Let superintendents and locally elected trustees spend that money on neighborhood problems and priorities.

It even sounds like — dare we say it? — local control.

Simple?

If it really was, this would happen quickly and painlessly. And without putting together a committee of education leaders and legislators.

But here’s the reality. Idaho’s elected officials love to say they support local control — and they love to bellyache about the strings attached to federal money. But Idaho’s elected officials have also created a numbingly cumbersome school budget. They’ve built this $2.7 billion Frankenstein’s monster, piece by piece and mandate by mandate.

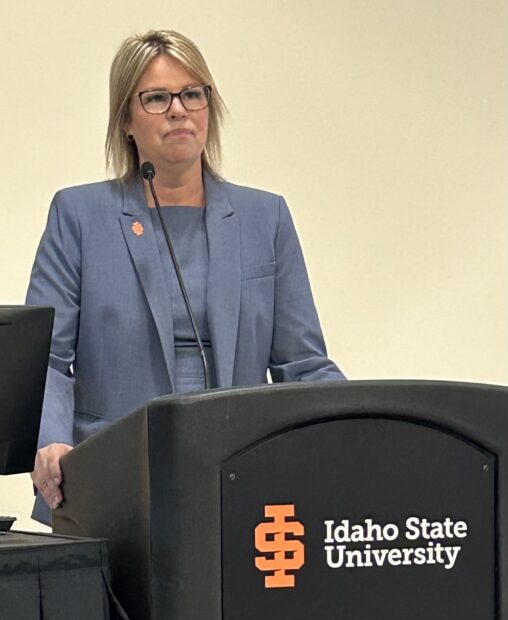

Now it’s up to that committee, assembled by state superintendent Debbie Critchfield, to take the state’s school funding formula apart and get rid of pieces that no longer make sense.

Good luck with that.

It’s going to take a lot of political skill and political will to kill off budget line items that lawmakers and education stakeholders fought for in the first place.

Critchfield’s endgame is straightforward enough. If Idaho strips out some past-their-prime line items, and gives the money to schools with no strings attached, locals will be better able to leverage the historic increases in state education funding.

When Critchfield’s committee met in Boise last week, members talked about the idea of getting rid of some of the line items.

One of Critchfield’s co-chairs, state Rep. Wendy Horman, talked optimistically about getting rid of the outmoded budget mandates the Legislature passed 20 or 25 years ago, and sending out 80% to 90% of state education dollars as unfettered, “discretionary” spending.

Again, it isn’t as simple as it sounds. As it is, districts spend 80% to 90% of their money on staff salaries and benefits — an unescapable fact when human capital is by far education’s biggest expense and largest investment.

And the biggest K-12 line item of them all, by far, goes straight into human capital. The career ladder injects $1 billion into the teacher salary pool, for districts to put into their local pay plans.

The career ladder isn’t just a state budget line item. Established in 2015, it’s an overwhelmingly popular political statement of purpose, an acknowledgement that the state must make a concerted commitment in order to attract and keep talented teachers. Politically, the career ladder isn’t going away any time soon, and even if it did, districts and charters will still spend the vast majority of their money on staff salaries and benefits.

What about a smaller — but also high-profile — line item?

During last week’s meeting, Horman, R-Idaho Falls, joined other committee members in calling the $72.8 million early reading line item a priority. Considering that literacy is one of Gov. Brad Little’s centerpiece education priorities, that line item isn’t going away either.

But what if the day comes that the literacy initiative has done its job, and the line item seems to be a little much? That would certainly qualify as one of those good problems to have — especially in a state where only 57% of kindergartners through third-graders were reading at grade level in the fall of 2022.

But if that happens, it would be easy to find something else to do with the money, right?

Not really. Legislators — even conservative legislators — are adept at adding pet projects to a budget. They’re not as good at going back and getting rid of them.

So if the committee goes after any line items, Critchfield knows she’s going to run into resistance.

“OK, who are we going to make mad when their sacred cow is now on the roasting grill?” she said in an interview after last week’s meeting.

Between now and January, committee members hope to overhaul a school funding formula that hasn’t been rewritten in 30 years. The committee has plenty of work to do. The group needs to figure out whether to build a formula around student enrollment or student attendance — a seemingly esoteric distinction, but one that has the state’s political leaders polarized. The group also needs to figure out whether, or how, to “weight” funding to provide more money to support special-needs students, or students in poverty.

But three decades of line items and add-ons add up to another big challenge for this committee.

Here’s the dirty little political secret: As much as legislators love to espouse local control, they don’t always walk the walk. And when state revenues account for 60.8% of public school revenues — the seventh-highest percentage in the country, according to a 2021-22 National Education Association report — Idaho lawmakers have no issue with exerting their will over where the money goes.

The result is a K-12 budget that earmarks state money for classroom technology, staff training, college and career counselors, safe and drug-free schools, and more.

Another dirty secret, as Critchfield notes, is that the line items provide some level of “comfort” to local districts. They can make it easier to negotiate contracts. And when local school leaders take heat over lackluster performance, the state’s spending restrictions can be used as a “weapon,” she said.

Nonetheless, Critchfield is undaunted.

“I guess we take the approach that, you know, we like to do hard things,” she said last week.

Like streamlining a funding formula — which is no simple task.

Kevin Richert writes a weekly analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for his stories each Thursday.