Janice McGeachin’s education indoctrination task force looks like an extension of her gubernatorial campaign.

The Republican lieutenant governor appears to have packed the jury box with like-minded hardliners. Three task force members — all aligned with the Idaho Freedom Foundation, the state’s one-stop shop for right-wing education messaging — are scheduled to make presentations at the group’s first meeting Thursday afternoon. We’ll have to wait and see if this group makes policy, but it seems built to make noise.

And there’s no ignoring the timing. Last week, McGeachin made her gubernatorial run official. Two days later, McGeachin’s task force co-chair, state Rep. Priscilla Giddings, R-White Bird, said she will seek the vacant lieutenant governor’s post.

Yes, it’s election season. Meanwhile, the open (and sometimes covert) backlash against the education system continues.

On Wednesday, McGeachin’s chief of staff Jordan Watters defended the task force makeup.

“Our task force contains a diverse roster of members, including many with extensive experience in education,” he said in an email. “We have met our goal of assembling a comprehensive task force that provides a broad representation of the community.”

But several leading education groups are on the outside looking in.

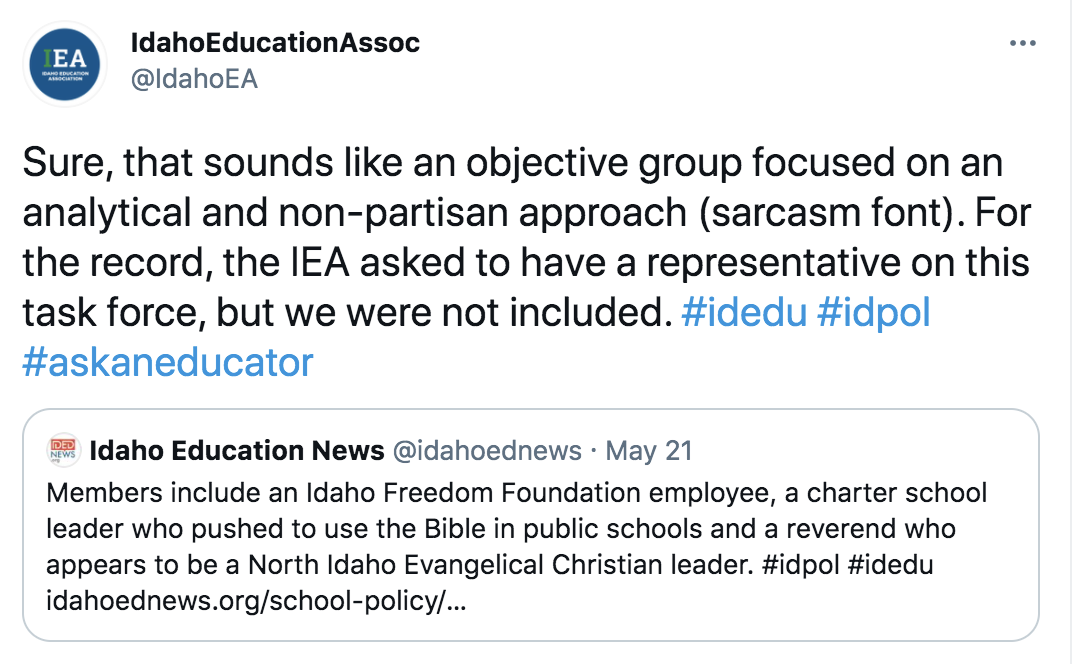

The Idaho Education Association sought a seat at the table, but was rebuffed. A day after McGeachin announced her task force’s lineup, the IEA fired off a salty tweet about its makeup. IEA President Layne McInelly doubled down on Wednesday, saying the group has little, if any, classroom experience.

The Idaho Education Association sought a seat at the table, but was rebuffed. A day after McGeachin announced her task force’s lineup, the IEA fired off a salty tweet about its makeup. IEA President Layne McInelly doubled down on Wednesday, saying the group has little, if any, classroom experience.

“The fix is clearly in on this task force, which has no intention of conducting an impartial, objective investigation,” he said. “The IEA, along with others who recognize the value of public education, will continue to advocate in the best interests of Idaho students, professional educators, and public schools. The same cannot be said for this farcical task force.”

To be sure, the IEA and McGeachin are political adversaries. When McGeachin jumped into the governor’s race last week, IEA President Layne McInelly issued a statement that said McGeachin “does not and will not prioritize policies that benefit public education.”

All that said, it’s not unheard of for elected leaders to listen to what their opponents have to say. McGeachin isn’t even feigning interest.

Idaho Business for Education — a less ideological group than the IEA — had no interest in McGeachin’s task force.

“It is highly unlikely that this will be an unbiased and independent committee, so there is no reason to lend any legitimacy to it by our participation,” CEO Rod Gramer said this week. “I don’t expect that anything helpful or worthwhile will come out of it.”

The Idaho School Boards Association did ask for a representative. Its president-elect, Melba trustee Jason Knopp, is on the task force. But the ISBA is watching with some reservations.

“We are taking the expectations one day at a time,” ISBA policy and government affairs director Quinn Perry said Wednesday. “We were surprised by the lack of education professionals selected on the committee, and it does have an apparent partiality to the Idaho Freedom Foundation.”

It perhaps goes without saying, but it’s still worth noting, that Gov. Brad Little’s office and Little’s State Board of Education will not be involved in the task force. “This is the lieutenant governor’s task force and the board wasn’t asked to participate,” State Board spokesman Mike Keckler said. “We will be observers.”

Again, it’s election season. But McGeachin is running for governor, not superintendent of public instruction. Sherri Ybarra’s State Department of Education won’t have a representative on the task force either. McGeachin didn’t offer the SDE a spot, but Ybarra didn’t ask for one, SDE spokeswoman Kris Rodine said.

“The superintendent would expect the group to listen to a variety of perspectives and learn the facts about what is and is not being taught in Idaho’s public schools,” Rodine said in an email.

This presumes that this task force will take a close, objective look at a complex and sensitive topic. That’s possible, but it doesn’t appear likely.

And if the task force comes up with policy recommendations, there’s no clear mechanism for its proposals to go anywhere. This isn’t quite the same as a legislative interim committee — formed and endorsed by lawmakers, who believe an issue deserves a deep dive over the summer. (Not that interim committees are assured of success. A legislative committee spent three summers reviewing Idaho’s school funding formula, and the 27-year-old formula remains unchanged.)

If, indeed, the task force turns out to be a political exercise, it’s still instructive. It would show, in stark relief, who McGeachin and Giddings want to hear from. And at least on Thursday, they don’t want to hear from everyday Idahoans; the five-hour meeting will be open to the public, but the task force won’t take public comments or field questions from the audience.

Sketchy as this process appears to be, at least McGeachin and Giddings are upfront about their apparent motives.

The same can’t be said for the still-unidentified person who complained about student harassment in a Boise State University diversity and ethics class.

Outside investigators could find no evidence backing up the March 15 complaint, and found no evidence that students have been ostracized over their race. But the investigators won’t say who made the verbal complaint — identifying the source as a “concerned community leader.” The university won’t name the complainant either.

Say this much for Boise State: Officials are dutifully honoring a confidentiality agreement with someone who helped cost the university $1.5 million. Soon after the complaint went public, legislators cut that sum from Boise State’s 2021-22 budget. Certainly, the flap over the diversity class played some role in the Legislature’s vote.

And before that happened, Boise State temporarily shut down a class involving 1,300 students — and then moved the classes online. All over a verbal complaint that investigators couldn’t verify.

That does nothing to discourage the next “concerned community leader” who wants to take a covert swipe at education.

So, say at least this much for McGeachin and Giddings. If their task force turns out to be a political apparatus, there won’t be anything covert about its work.

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for it every Thursday. Due to the timeliness of the topic, this week’s analysis was published on Wednesday, May 26.