SALMON — Parents, grandparents and neighbors in this small mountain community were confident in the days leading up to last month’s school bond election. This would be the year Salmon finally got a new school, they predicted.

Their certainty was surprising because voters had rejected their local school district’s previous 12 requests to pay for a new building by increasing property taxes. And the stakes hadn’t changed since the last request failed with 59% support, eight points short of Idaho’s required supermajority threshold for school bond elections.

But this election was different. Salmon still needed about $29 million to replace its moldering Pioneer Elementary. However, school district leaders — the superintendent and board of trustees — weren’t asking for the money this time, after their relationship with skeptical voters had grown strained during previous bond campaigns. Instead, district parents and grandparents — even Salmon residents with no connection to the district other than an address — took the lead.

A volunteer group, the Salmon School Needs Assessment Committee, worked for about 15 hours a week over 18 months to find out what it would take for voters to support a new school. The committee came up with a unique financing plan, which calls for a $20 million bond, the method used by most Idaho school districts to finance high-cost projects. But the plan also includes donated building materials and sponsorships — $20,000 gets your name on a classroom, for instance.

In the months leading up to the election, committee members pleaded with their neighbors — in the newspaper, on porches and in smoky Main Street bars — to support their “frugal” plan for “simple, sustainable and secure” schools for their children. By election day, the volunteers knew where most everyone stood, because they had reached out to most of them. And they knew Salmon’s long — and sometimes bitter — debate over a school bond would finally be settled.

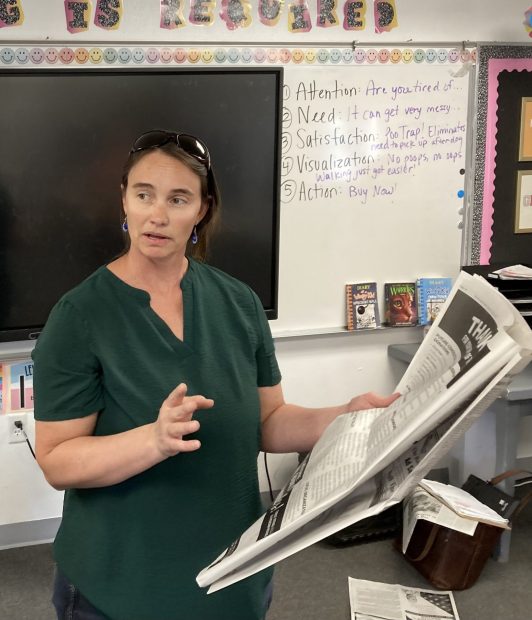

“If our community cannot get behind this bond, there’s not a bond that they would ever get behind,” said Mallori Wing, a fifth-grade teacher at Pioneer and member of the committee. We put “everything on the table.”

Ultimately, the confidence in a positive result on election day was well-founded. On May 21, turnout at the polls rivaled a November presidential election, and 72% of district voters approved the bond, securing $20 million toward a new building for preschool through eighth grades.

The momentous victory is about more than one building, however. In a state where failed bonds are the norm, Salmon’s community-led bond campaign may have created a new playbook that could help rural communities across Idaho struggling to get hold of facilities money.

Torn and tattered: Salmon’s school facilities problems

In her small office at Pioneer Elementary, Principal Jill Patton fought back tears while explaining how the building — not the education, the teachers or the town — has deterred families from moving to the area. The “delightful” town welcomed her when she arrived from Montana in 2020, and “it’s a fabulous place to raise kids.”

“They don’t know the teachers, they don’t see the amazing things that are going on with the kids in the classrooms,” she said. “They have to judge the book by the cover.”

If Pioneer was a book, its cover would be torn and tattered — and probably a little stinky. Opened in 1959, the school’s foundation is crumbling, creating ripples in the floor that trip up the tiny feet of its students. Custodial staff crawl through raw sewage to fix backed up lines. Drainage on the site is poor and runoff leaks into the building. Bathrooms and the cafeteria are inaccessible to students with disabilities.

And the district’s facilities challenges aren’t confined to the elementary site. Bus services for the junior/senior high school, located across U.S. Highway 93 from Pioneer, go through the elementary school. That means sixth- through 12th-graders who ride the bus must cross the busy highway twice per day.

“It is dangerous,” Patton said. “People aren’t always very careful at stopping.”

Patton will become the district’s new superintendent this summer after 30 years as a public school educator. She wasn’t in Salmon for the last bond election, which would have financed a K-8 school building to replace Pioneer. But she understands what went into it — and why it was “gut-wrenching” when it failed.

“There were a lot of great people that put a lot of effort into that,” she said. “They came as close as they ever had.”

Per state law, 66.7% voter support is the benchmark for school bonds to pass. Idaho is one of two states with a supermajority requirement for school bonds.

Less than 59% of Salmon voters supported the 2019 proposal for a $25.6 million bond. That was just the second time since 2005 that a Salmon bond garnered majority support. Between 2009 and 2013, seven bond measures received less than 50% approval.

The 12th consecutive failure “took the wind out of everybody,” said Tammy Dahle, the school board chair who became a trustee that year. Voters were skeptical that a new building was necessary after the district had vacated two other buildings.

From 2006 to 2007, the district moved students out of Salmon Junior High and the Brooklyn Intermediate School, buildings plagued by infrastructure issues. Sewage leaked down the walls and the water was undrinkable at the junior high, while the intermediate school — which housed fourth- and fifth-graders — was also inaccessible for students with disabilities.

Skepticism among voters was fueled by the fact that the county moved into the Brooklyn building after the district left. Americans with Disabilities Act compliance standards for government buildings are “very different from school buildings,” Dahle said. “I think people just didn’t understand.”

After the 2019 election, school leaders took a step back and made no immediate plans to run another bond. The election had gotten ugly. Political cartoons in the newspaper mocked the superintendent at the time, and trustees grew accustomed to getting yelled at.

“It was like, ‘Holy cow, we’ve just taken a beating,'” Dahle said. “We don’t even want to talk about a bond.”

Retirees who want to be left alone: A voter profile of Salmon

Salmon’s opposition to school bonds over the decades hasn’t just been motivated by a lack of trust. Demographics have played a key role, too.

A $20 million, 20-year bond each year costs property owners $122.72 per $100,000 of taxable assessed value, and Salmon isn’t a wealthy town. While it has the characteristics of a resort city — natural beauty chief among them — Salmon didn’t evolve the same way as Ketchum or McCall, where deep-pocketed tourists bolster the local economies.

Salmon, and wider Lemhi County, grew up as a logging region, and while the logging industry has since dwindled, its identity largely remains working class. Today, Lemhi County’s top employer is the Salmon School District, followed by the local hospital and a mix of construction and manufacturing companies. Other locals work for the U.S. Forest Service or Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Roughly 93% of the county is public land. That attracts visitors, and tourism is important to Salmon’s economy. But the abundance of public land cuts out a huge portion of taxable property for local governments, increasing the tax burden on private landowners. Many of those property owners are retirees on fixed incomes, and some moved there from states like California or Washington to escape high taxes.

The median household income in Lemhi County, $49,216, is about $23,000 less than the statewide median, and the county’s 14% poverty rate is 3.3 percentage points higher than Idaho’s overall, according to U.S. Census data.

The county also has a much higher percentage of people 65 or older — 31.4% compared to 17% across the state. And older people are less likely to have young children or a stake in the school district.

“Some of them just did not have the interest in the school or what was going on,” Dahle said. “They’re coming here to retire and be left alone.”

In other words, district voters have good reason to repel proposed tax hikes. When a committee eventually formed in 2022 to study the district’s financial options, the group tried to account for that natural resistance.

“We knew we had to do something different, with not putting the burden completely on the taxpayer,” said Windy Schoby, a district mom and member of the Salmon Schools Needs Assessment Committee.

Nothing fancy: Volunteers seek community input on new school

In the fall of 2022, two-and-a-half years after the last failed bond, former Salmon Superintendent Troy Easterday put out a call for community volunteers to broadly advise the board of trustees on everything from books read in classrooms to athletics.

“All we could talk about was the infrastructure of the current schools,” said Breann Green, a leading member of the Salmon Schools Needs Assessment Committee.

About a dozen people attended the first few meetings with district leaders, then the group grew to 30 regulars as it started to meet on its own. Some volunteers, like Green, Wing, Schoby and Jim Bob Infanger, have children or grandchildren who attend district schools, or will soon. Others, like Rick Sessions, don’t.

It’s a mix of “do-gooders” willing to answer questions from the community, Infanger said.

That winter, the group met for several months to study the district’s needs, when it wasn’t a foregone conclusion that the advisory committee would recommend another bond. In the spring of 2023, the committee went public and organized community meetings to solicit feedback. Hundreds of people attended back-to-back meetings in June and offered their ideas:

- Have you sought donations?

- Have you asked the state for help?

“Everything someone had suggested, we did it, and if it didn’t work, we documented why it didn’t work,” Wing said.

The work sessions confirmed the obvious: The district needed a new school building, as it had for decades. But the conversations also revealed what hadn’t been obvious before: What exactly it would take for voters to support a tax increase to pay for it.

The building had to be practical, the voters said. And they wanted every detail about its financing to be transparent. Wing recalled some of the feedback:

- “If we could see a plan and what our money is buying, then maybe we can support it.”

- “As long as it’s not fancy.”

- “We don’t need the Taj Mahal.”

One other prerequisite emerged from the community dialogues. Voters wouldn’t support a bond worth more than $20 million. That’s about two-thirds of the cost to build a modest school, so the committee got to work brainstorming how it could come up with the remaining $9 million.

The volunteers met for about two hours every Monday, on top of meetings with individual voters, organized events and media appearances to promote their work. They toured school buildings across Idaho and in Montana. Infanger estimated the average committee member put in about 15 hours per week over 18 months.

The project gained steam with its first big donation, which led to more. R&M Steel, a Caldwell manufacturing company, donated a 70,000-square-foot metal building structure. Locals Kathy and Ed Tolma offered 18,000 cubic feet of gravel. And the QB Corporation, a Salmon-based manufacturer, gifted a beam entryway.

Altogether, donors have pledged $3.2 million in construction costs. And the committee cooked up some more unique methods to raise funds, like selling classroom sponsorships at $20,000 a pop, which has so far raised $600,000.

Another $2.6 million is coming from House Bill 521, the sweeping school facilities funding bill that the Legislature passed this year. Gov. Brad Little’s plan calls for $1.5 billion in new state spending over the next decade, meant to address a growing backlog of school facilities maintenance across the state.

Little referred to Pioneer Elementary in his January State of the State address, when he announced the blockbuster bill. Little and his staff toured the school in September during a visit to Salmon.

“We’ve all seen the pictures and videos of some Idaho schools that are neglected — crumbling, leaking, falling apart,” Little said, referring to the Idaho Statesman and ProPublica’s in-depth coverage that showed school infrastructure coming apart at the seams across the state. “In one school I visited, raw sewage is seeping into a space under the cafeteria.”

In Statehouse debates on the bill, Salmon became the poster child for Idaho’s failing school buildings. But ultimately, its share of the state funding was only a fraction of what the district needs. The HB 521 funds are divided between school districts based on attendance, meaning big districts in urban areas are getting the largest shares. Just nine of the state’s 116 school districts will get enough money from HB 521 for a $30 million elementary school.

“There is a source of frustration,” Patton said. “I feel like part of the motivation for that bill was what people saw here. Well, $2.6 million doesn’t build a whole lot.”

Still, the needs committee appreciated the help. The HB 521 funds are an important piece of the $9 million the group is cobbling together to supplement the bond. Like the donations, the state aid “really built a lot of momentum,” Infanger said.

‘No shaming, just information’: Media blitz sells bond to voters

After settling on a plan — a $20 million bond measure, combined with donations, state money and real estate sales of district property — the committee launched a media blitz to promote the bond.

That’s one of the key differences between the school district fronting the bond effort, as it had in the past, and a community-led effort. Idaho law prohibits school officials from using taxpayer resources — including their working hours — to advocate for a bond. The Idaho Falls School District last year faced fines for using district funds on bond-related material that said schools are “overcrowded” and “aged.”

But no such restrictions existed on the committee, as long as district employees, like Wing, worked with the group outside of school hours. The committee flooded news and social media channels — with radio spots, Facebook videos and newspaper advertisements — promoting the bond.

In an interview with Idaho Education News, Green proudly flaunted the last of 13 weekly ads that ran in the local newspaper leading up to the election. The full-page notice thanked a lengthy list of bond supporters, from donors and sponsors to guests appearing on the committee’s series of “Facebook Live” videos.

Salmon’s crumbling school buildings have already been the center of widespread media attention. Coverage from EdNews, the Statesman and Nick News — a Nickelodeon documentary series — have highlighted the district’s struggles to finance new facilities.

But headlines weren’t enough for the committee — it needed votes. And much of the debate over the bond measure played out in the pages of The Recorder Herald, Salmon’s local newspaper and one of Idaho’s oldest periodicals, which doesn’t publish online.

In a recent print edition, Bruce Barnes of North Fork declared that he would not support an increase in property taxes. “Simply put, I cannot afford it.” Christopher Lanski of Salmon countered that paying for a new school is like replacing a beloved old car when repair costs have outpaced its value. “It’s time to remember proudly the past yet work towards a stronger future,” he wrote in support of the bond.

Committee members addressed concerns raised in the paper and online. When Virginia Perry of Salmon wrote that she wouldn’t support a new school building unless the district sold off excess property, the committee acknowledged that “we aren’t financial experts,” but the financing plan did call for offloading district property in support of the new school.

A few days before the election, committee leaders were confident the bond measure would pass, as if they had already tallied each vote — and they nearly had. Early in the bond campaign, the volunteers held a strategy session, where they read through the names of Salmon School District’s 4,999 registered voters and assigned a committee member to canvas for their “yes” votes.

“When we say we have tried to talk to every single person, we really did,” Green said. In one-on-one conversations, committee members say they tried to remain positive and avoid the toxicity of previous bond measures. “No shaming, just information,” Wing said.

In the end, the committee’s “sincerity and authenticity” made the difference in the bond campaign, according to Patton. “There’s no substitute for sitting down with somebody and talking,” she said. “They went in with, ‘If we’re going to make a change for our schools, then we need to know what people are worried about.’”

A playbook for future bond elections?

The bond measure had 568 more “yes” votes than the 2019 election, a 34% increase. In bond elections since 2005, turnout this year was second only to November 2012, which was also a presidential general election year when turnout is typically high.

“We were on pins and needles until they posted the results,” Green said, “then, truly, super happy.”

The committee’s work isn’t done, however. It will now advise the school board on implementing the financing plan. Trustees have said they support what the committee came up with. But there are still “puzzle pieces” to maneuver, Green said, like selling district property. “It’s seriously a shoestring budget that we are still actively working on.”

Those who closely watched what the committee accomplished hope other communities take notice. “That’s how it should be done every time,” said Rep. Rod Furniss, R-Rigby, who represents Salmon in the Idaho House.

Furniss is among a handful of lawmakers who have pushed to ease the supermajority requirement on school bond measures. But that doesn’t appear to have much support in the Republican-dominated Legislature.

Meanwhile, school bonds have become less successful in recent decades, according to an analysis by EdNews. Between 2001 and 2011, districts had a 61% bond measure success rate, but it fell to 44% between 2011 and 2023.

In Salmon, school leaders believe the volunteers’ methods could be repeatable elsewhere. The community-driven effort rebuilt trust, and finally convinced voters that “it was time to build a school,” Dahle said. “I would absolutely encourage any community to think about doing something like this.”