Genevive Poynter has revived her 19-year-old dream of becoming a teacher.

She was on the home stretch of completing a bachelor’s degree at Idaho State University when the youngest of her four children was born. She knew at birth that Ethan would need special attention from her as he grew up.

“I had to make that choice, you know, stay home with my son, or finish school and go to work,” she said.

Then a single mother, she couldn’t stay home full-time or afford expensive therapy. So, she researched how she could help her son and she followed him through school, working jobs in the same hallways as certified teachers, whose education levels she’d nearly matched.

She most recently began working as a secretary at Falls City Academy, an alternative high school in Jerome. But next school year, she’ll be returning to Falls City as a teacher, thanks to a new teacher preparation program in Idaho.

Poynter, 41, recently joined the grow-your-own teacher program at the College of Southern Idaho.

CSI’s and other grow-your-own programs across the U.S. provide an alternative path to teacher certification with aims of bringing more educators into the field. Some focus on tapping paraprofessionals to become certified teachers. Others eye prospective candidates who are still in high school, and others look to increase the number of teachers of color in classrooms.

CSI leaders are attempting to blend all those goals, while improving teacher retention rates in rural schools.

Before grow-your-own, those interested could only become teachers through a traditional route — finishing a bachelor’s in a four-year education program; via Teach for America; or another State Department of Education-approved alternative path — like ABCTE, the American Board of Certification for Teacher Excellence.

Like traditionally trained teachers, CSI grow-your-own participants must earn a bachelor’s degree, but it can be in a different field, accommodating for career changes and candidates who have completed dozens of credits toward another degree.

While fast-expanding, CSI’s program is still young. Certification courses were first offered in the fall of 2018 and participation has leaped from 18 to over 150.

“I kind of built the plane as I was flying it,” Janet Avery said of her time as was one of the program’s first instructors.

A ‘revolving door’ problem

Idaho’s teacher retention rates have hovered around two percent below the national average over the past half decade, but in rural districts, retention is consistently lower, a 2018 Idaho State Board of Education report found.

Rural districts have teacher “revolving doors,” said Christina Linder, director of CSI’s program.

(Disclosure: Linder serves on EdNews’ board of trustees. Board members do not have influence over editorial decisions.)

Recruiting difficulties compound the challenge. Former Twin Falls Superintendent Wiley Dobbs and Linder have been meeting with the Idaho Rural Education Association to float using grow-your-own as a solution. Dobbs says retention and recruitment are among the most pressing challenges facing rural school administrators.

“It’s very difficult to get teachers, but for smaller districts, it’s even more difficult because they have to talk people into moving into a small community. ” Dobbs said. “And while they’re lovely communities, not everybody wants to, especially people that already have families.”

CSI’s program was designed, in part, to remedy that problem, certifying community members to be teachers, as they have already laid down roots in their home districts. Directors hope grow-your-own teachers like Poynter, who has lived in southern Idaho all her life, will stay in their communities.

In Jerome, that’s especially important, Avery said. She has seen many teachers leave for the nearby Twin Falls district in her decade plus as Jerome’s director of curriculum. And on paper, it appears Twin Falls boasts its fair share of pull factors.

Comparing Twin Falls to Jerome, per-pupil spending is higher, the average teacher salary is higher by a few hundred dollars and a greater share of teachers have six or more years of experience. Avery said some teachers who first come to Jerome in search of work end up living in Twin Falls because of a tightening squeeze on Jerome’s housing market. Those teachers frequently take jobs in Twin Falls after a year or two, she said.

“We spend a lot of time and resources to train teachers who then — if they’re not from our area — tend to leave,” Avery said.

Some national research shows grow-your-own teachers are more likely to stay in their home communities, and some studies suggest those teachers stick around because they have strong connections to their schools.

Poynter has been with her school since its founding almost three years ago, and her attitude mirrors the data.

“Falls City Academy is my home. They’re my students. They’re my kids. And well,” Poynter said, her voice softening, “they’re just very important to me.”

Closing race and ethnicity gaps

In some states, grow-your-own programs have launched with a focus on getting more candidates certified as teachers who are bicultural, biliterate and people of color. Programs focused on certifying Hispanic teachers, for example, prioritize getting more Hispanic teachers into schools where non-Hispanic-majority staffs serve Hispanic-majority student bodies.

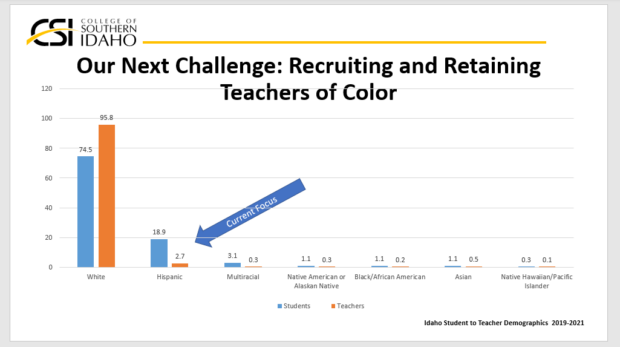

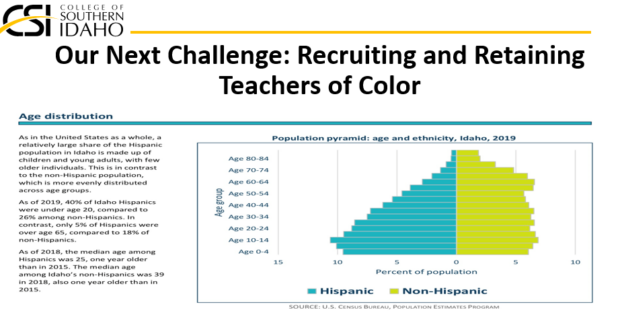

A similar program may get started in Idaho, said J.J. Saldaña, community resource development specialist for the Idaho Commission on Hispanic Affairs. While nearly 19% of Idaho students are Hispanic under 3% of the state’s teachers are.

Gov. Brad Little’s office is in early talks with the Commission about starting a grow-your-own program geared at certifying Hispanic teachers, Saldaña said. Still, nothing has been cemented, according to an email from Emily Callihan, spokesperson for the governor’s office.

In the meantime, CSI’s program is making a concerted effort to close the gap between Hispanic teachers and their white peers, said Linder.

The results aren’t yet conclusive.

In a 2019-2020 federal report, CSI reported that 10% of its grow-your-own candidates were Hispanic. That proportion outweighs the share of Hispanic teachers in Idaho, but still lags behind the share of Hispanic students. Hispanic participation in her program has likely risen since, Linder said, but more recent demographics aren’t available.

Stakes are especially high in south-central Idaho, where the highest share of Hispanic Idahoans live, per Commission on Hispanic Affairs data, and where CSI operates — the first Idaho college to be designated as a Hispanic-Serving Institution by the federal government, as Boise State Public Radio reported.

Part of the Magic Valley, the Jerome School District is majority-Hispanic or Latino, and about a quarter of its students are learning English. The district runs a dual-language immersion program, in which a 50-50 split of native English and Spanish speakers learn from biliterate teachers, half the time in English and half in Spanish. But it’s difficult to find enough teachers to cover the 50 students in each elementary grade who participate, Avery said, and as some officials hope to double the program’s size, Spanish-speaking teachers could be in even greater demand.

Falls City Academy, where Poynter will make her teaching debut, is also majority-Hispanic, according to EdTrends.

Having staff aboard who share a socioeconomic or ethnic background with the students at Falls City makes it so, “when parents come in and out, they feel comfortable,” Poynter said. “They feel like there’s someone that’s going to understand them, someone that can relate to them.”

More grow-your-own programs could offer other schools the same benefits.

Growing grow-your-own

Though CSI’s program participation has eclipsed 150, its teachers represent only a sliver of the 19,000 teachers in Idaho K-12 schools.

But barriers to expanding the existing program and building new ones are receding.

Although the state teacher’s union has opposed some efforts to create alternative certification programs, it too is lending support to grow-your-own.

The Idaho Education Association “would really encourage” people to get into the CSI program because it provides mentorship and classes aimed at “teaching how to teach,” said Peggy Hoy, IEA’s National Education Association director. The state union prefers CSI’s program to certification through a popular alternative route — ABCTE, which can be completed online and without the mentorship mandated in the CSI program — for the same reasons. Though she argued traditional paths into the profession are best, Hoy would “like to see more” grow-your-own participation, she said.

Participation is getting easier. National grant money is now available to foot between 90% and 100% of the $5,000 bill to participate in CSI’s program, and a partnership with a Boise State University multidisciplinary program is helping candidates finish the college degrees they need to become certified teachers.

More cash is flowing into K-12 schools, too, priming the pumps for new programs.

Two thirds of a historic $440 million infusion of federal coronavirus relief funds have already hit Idaho coffers, and school districts — which get the final say in how 90% of the K-12 money is spent — got access to the bulk of it July 1. As the next school year nears, Linder and Dobbs suggest districts use some of their stimulus as seed money to start local grow-your-own teacher programs.

The money is meant to go to high-poverty schools to support students most impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. Dobbs encourages districts to target their new grow-your-own programs at recruiting current high school students to become teachers; if they do, a new wave of educators could emerge from a group of students who felt the brunt of learning losses and the fallout of the pandemic writ large.

Other districts’ needs loom large enough that they can’t afford to prioritize new programs.

Minidoka School District’s director of student achievement Ashley Johnson is a steadfast proponent of the CSI program’s value, but spending money on grow-your-own hasn’t even been a discussion among district officials, she said. The district has pivoted from buying technology to support remote learning to backfilling staff positions as the three rounds of federal relief have come in. It will allow new staff members to intervene when students are falling behind due to the pandemic, Johnson said. That pressing priority has risen to the top.

In Jerome, a new program hasn’t been discussed either, as of June 1.

“Superintendents are still struggling with the release of those funds. And … there may be some other needs of those funds,” said Avery.

Avery is leaving to be superintendent of the Potlatch School District, and though she’s just jumping into the district’s funding situation, she says she’ll continue encouraging people to participate in grow-your-own programs.

“I see this as a benefit anywhere in Idaho,” she said.