Twenty-five years ago, teachers unions, school administrators and trustees protested the decision to add charter schools to Idaho’s public education system.

They feared that charters would siphon their top-performing students, most engaged parents, highest-performing teachers and millions of dollars, leading to the collapse of traditional schools.

Their fears were unfounded.

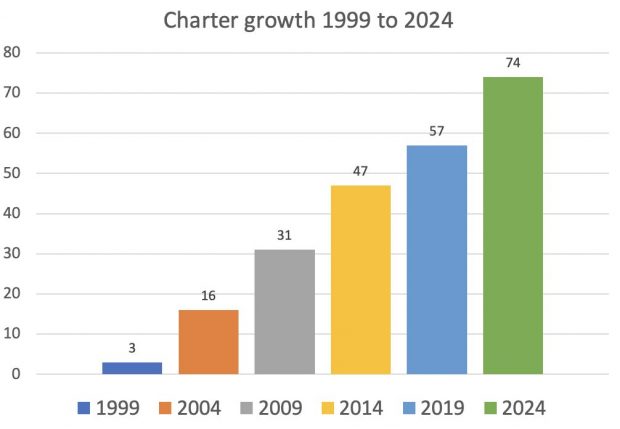

While charters in Idaho have grown rapidly, they haven’t destroyed the public school system. They instead filled a need in a fast-growing state, promoted innovation, brought in millions of federal dollars and created alternatives to mainstream education practices.

“Their fears were overblown,” said Terry Ryan, CEO of Bluum, a Boise nonprofit charter support organization. “They should have had more faith in our parents and our educators to step up and take advantage of the opportunity to create new learning opportunities for our children.”

Idaho now has 74 charter schools serving 10% or 30,000 of Idaho’s public school children.

And they serve a wide assortment of free options. For example:

- In Idaho Falls: Alturas Academy’s International Baccalaureate program prepares students for college while earning an internationally-recognized diploma.

- In Coeur d’Alene: Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy’s rigorous coursework was founded to develop academic excellence and curb lowering standards.

- In Nampa: Elevate Academy is uniquely focused on workforce readiness, industry partnerships and inspiring young people who aren’t succeeding in traditional classrooms.

- In Fruitland: Treasure Valley Classical Academy trains the minds and improves the hearts of students through a content-rich, classical curriculum that emphasizes virtuous living, traditional learning and civic responsibility.

“I was impressed within the first 10 minutes and sold within 15 minutes,” said parent Katie Cueves Fuentas, who has two children attending Island Park Charter School near the Idaho border with Yellowstone National Park.

Charter-school momentum isn’t subsiding. Despite a proliferation of charters, demand for seats outpaces availability. Nearly 11,000 students were placed on waiting lists at the start of this year. And while enrollment numbers dropped in traditional schools this year for only the second time in history, charter enrollment went up.

“This is an indication that parents have a vision for the future of their children that they believe a charter school can help them fulfill,” said Jason Bransford, CEO of Gem Prep Innovation Schools, which embarked on a multi-year expansion, resulting in seven campuses and one slated to open in 2025.

Sen. Janie Ward-Engelking wasn’t sold on the idea as a Boise teacher in 1998. She expressed retirement concerns for educators moving from a traditional school to a charter. She was also concerned about accountability and bringing innovative practices back to traditional schools.

Today, the legislator is a member of the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee and the Senate Education Committee. She has school financing concerns for both charters and traditional schools, but she believes charters have been positive.

“It’s always good to provide opportunities for students, because not every child fits a mold,” Ward-Engelking said.

Charters focus on specific programs and many families are interested in what they offer. Charter enrollment is up while public schools are down. But concerns persist.

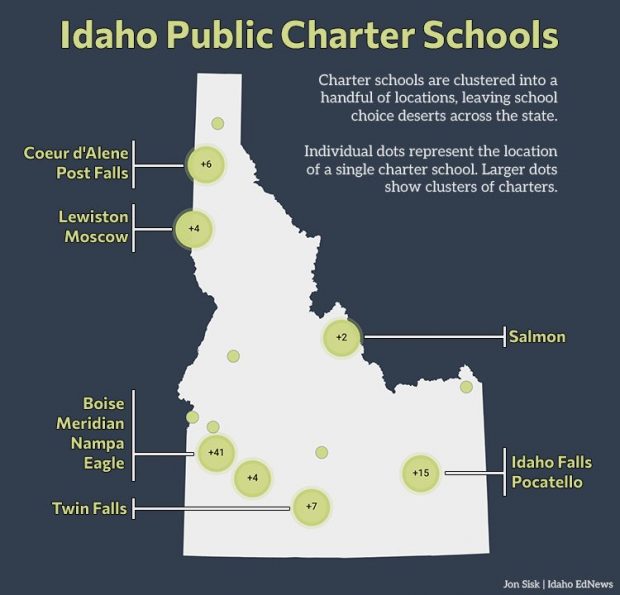

- Charters are not available to all students as they cluster in population centers, leaving rural students without the choice.

- They were intended as learning laboratories for public schools to copy — but that hasn’t happened.

- And oversight and accountability has come under scrutiny.

- Their growth could outpace state control.

Overcoming obstacles when opening a new school is challenging, yet robust growth has defined the movement for 25 years.

Starting a charter school isn’t easy, leaders recall

Four years after the first charter school opened in 1998, Kelly Edginton was then a charter teacher and Dan Nicklay was guiding Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy’s commencement years. CDA charter is consistently one of the state’s top academic performing schools.

Boise Rep. Fred Tilman, R, pushed through legislation approving charters on July 1, 1998. Three schools opened that year located in Arco, Moscow and Boise.

“At the time I didn’t have an expectation of how large or fast the charter community would grow. As I participated in that community, though, I was surprised and happy to see the rapid growth,” Edginton said.

Nicklay recalls problem solving with the Idaho Department of Education. There were literally no answers because they were up against unique, never-before-encountered issues.

“Our early years were an adventure. The charter laws were pretty sketchy, and no one really knew what they were doing — either the state or school administrators. We made it up as we went, and it was exciting and terrifying,” he said.

No matter how well conceived and planned, every new charter school has a rough first couple of years on-boarding new employees, indoctrinating them into the school culture, establishing procedures, maintaining buildings and working with school budgets.

It’s “exhausting,” Nicklay remembers, adding that there were no road maps to consult. “Remember, when we started, there were no other people who had been through it.”

What makes charters different than traditional schools

Charter schools utilize unique funding methods for new facilities, and have greater autonomy over curriculum, instructional methods and financial decisions. They typically focus on a specific program or method: college preparation, classical education, STEM, expeditionary learning, dual language or brain-based learning.

And Bluum is at the forefront of bringing choice to Idaho. A $22 million federal grant in 2018 helped the nonprofit kick off a growth surge of 11,500 new seats and 23 new schools. This fall, another $24.8 million in federal money was awarded. The plan is to increase student seats by 5,900 and add 13 more schools by 2028.

About 82% of charter schools are authorized by the Idaho Public Charter School Commission. The agency monitors the financial health, academic performance and regulatory effectiveness of 60 schools. The six-member commission approves new schools and also recommends closing failing schools.

The commission approved three schools to open in 2024 and three are petitioning to open in 2025. Traditional school districts authorize 18% of charter schools.

Charter administrators can be state certified or may hold a charter school administrator certificate. Teachers may be state certified or hold a charter school-specific teaching certificate, which is not transferable to a traditional public school district.

Charter schools take the same assessments as public schools. They often call the school leader an executive director or a CEO; many smaller schools choose charter administrator or simply principal.

They cannot charge tuition, levy taxes or issue bonds. Charters are nonprofit organizations and their board of directors are appointed, not elected.

They construct facilities with various funding sources: philanthropy, state credit enhancement, Federal Charter School Credit Enhancement Program, bank loans, USDA for rural schools, charter school facility per-pupil allocation from state, state revolving loan fund and Community Development Financial Institutions loans.

Special education students attending charters make up about 10% of the population, while the number in traditional schools is about 11.3%. Minority students account for about 16.8% of the population, while in traditional schools that number is 17.3%.

What didn’t work — charters sharing innovation

There’s some evidence that charters challenge public schools to improve but it doesn’t appear that many of their practices are being adopted.

Charters are flexible and offer specialized educational programs, meet the needs of specific student populations, use innovative teaching methods and provide more accountability. The plan was to spread and share innovative ideas and inspire change at public schools.

Idaho Public Charter School Commission chair Alan Reed said, “Generally there has not been any sharing of the new teaching opportunities charter schools develop.”

Ward-Engelking agrees. The premise was for charters to be creative and innovative, and collaborate with traditional schools. New practices would be replicated. “That did not work,” she said.

Edginton, Idaho Virtual Academy executive director, said the pandemic demonstrated the need for all schools to embrace new ideas. IDVA is the state’s largest online charter school with approximately 2,000 students attending two campuses: the virtual academy and Insight School of Idaho.

“I do believe charter schools have been pioneers of new educational methods and approaches in Idaho. When traditional schools are faced with losing students to other schools, they have to look closely at long-held practices, embrace change and adapt to new methodologies,” Edginton said.

Nicklay, principal of Coeur d’Alene Charter Academy, is disappointed that the charter movement’s original purpose as “learning laboratories” gave way to simply being an alternative to regular public schools.

“I know that it’s hard to change the system, and I know that there will always be some resentment toward charters that prevents public schools from openly emulating charter techniques,” Nicklay said.

But a collaborative culture ultimately benefits students. “Sharing successful charter school and traditional school practices promotes a culture of continuous improvement and provides diverse learning opportunities tailored to individual student needs, fostering a more robust and adaptable education system,” Edginton said.

Fears still linger because of authorizing and school saturation

Charter expansion faces two barriers: Idaho has one prominent charter authorizer and there is concern that Idaho already has enough charters. Traditional school districts authorize 14 charters and the public charter commission 60.

Despite the ability to do so, higher education institutions have not authorized a school, Ryan told EdNews in an earlier interview. “None have taken it up in Idaho, but we’d like to see a university take on this responsibility.”

Bluum has up to $750,000 in grant funds to help strengthen authorizers, and has offered that support to the public charter commission.

It was a difficult year for the public charter commission — leadership resignations, criticism from lawmakers, rejecting funding for additional portfolio managers, legal challenges and staff director turnover. The commission selected a new director this month, Jacob Smith, the third person to permanently occupy the role in 2023. Alex Adams, Gov. Brad Little’s budget chief, served as interim director for much of the year.

Edginton outlined her concerns: overreaching regulations, an adversarial attitude, a one-size-fits-all approach and usurping parental choice. “As has been well-documented, the commission has become a challenge to the schools it authorizes,” she said.

It should support growth, partner with schools, welcome innovative models and champion educational freedom. “That was the original vision and intent of a state charter commission when it was established by statute in 2004. Unfortunately, Idaho’s charter commission … got hijacked by a top-down, technocratic ideology that created division and discord,” Edginton said.

Overregulation is on Nicklay’s mind, too. “The Legislature continues to add requirements for all schools that make it really hard to pursue a mission or do anything special. It’s getting harder and harder to be different from other schools. Remember that charter schools were supposed to be ‘free from many regulations,’ so that they could innovate.”

Read about Idaho’s first charter school.

Edginton suggests reforming policy to allow maximum parent empowerment and loosen inhibitive red tape and regulations.

“I think simply providing an alternative for kids who are dissatisfied or feel unserved in their regular public schools is the most important thing. One of the huge benefits of schools of choice is that they ideally draw teachers who are passionate about their specific mission, and students who are looking for that style of delivery, and that creates engagement and ultimately success. This does not have to be viewed as an indictment of the system; it’s simply a recognition that kids have different goals, interests and learning styles,” Nicklay said.

Nicklay believes there’s a real threat of saturating the market with too many choices. “The challenge is resisting the urge to simply flood the state with new charters that don’t really offer anything new.”

“I have always felt that the quality and diversity of charters is far more important than the sheer number. I worry that unchecked growth of charters that are either poorly-conceived or redundant of other charters in the same area will both water down the market and give the movement as a whole a bad name,” he said.

Bluum recognizes that concern. The new $24.8 million federal grant won’t duplicate what Bluum helped accomplish in the previous five years — funding unprecedented growth. The money will instead be used strategically, targeting career technical opportunities, academic needs, demographic needs and underserved populations.

What’s next for charters in Idaho

After 25 years of steady growth, dozens of distinct charter schools stretch from Rathdrum and Coeur d’Alene in the panhandle, to Pocatello and Blackfoot in the southeast. The community is diverse, serving students with severe emotional trauma, to college-bound teens focused solely on science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

And more growth is on the horizon, with millions of federal dollars pushing into Idaho for additional schools. Expect new schools being built, more teachers and administrators being hired, expanded opportunities for new authorizers and an impact to the broader education system.

“Our public charter schools serve all students. The argument that charters ‘skim’ the most engaged or smartest students is false. If you don’t believe me, visit an Elevate Academy, or Gem Prep Nampa, Future Public School, Treasure Valley Classical Academy or the Cardinal Academy,” a cost-free public school for pregnant or parenting teen moms and dads, said Ryan.

Idaho is trending to be a leader. The percentage of students attending charters skyrocketed from nothing to nearly 10%, placing Idaho among states with the highest percentage of charter students. States like Texas, Minnesota and Oklahoma enroll thousands more but as a percentage of all school-age students, Idaho is on-par, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Around Idaho 30,000 students attend charters.

Nearly 11,000 students on charter school waitlists across the state and steady enrollment gains prove parents want choice. The highest percentage of enrollment growth last year occurred at charters: 10 reported increases of more than 22%. Gem Prep Meridian South’s population more than doubled, from 194 students to 425; Pinecrest Academy experienced a 48% increase and The Academy in Chubbuck grew by 37%, or around 200 new students.

Reed said, “I have always seen when parents are given options, they take advantage of what’s best for their children. Over the years, the schools are getting better and better, giving students more creative educational opportunities.”

Ryan predicts that more than 25% percent of all public school students will be attending a charter in another 25 years.

“I think our growing school districts will see the advantage of partnering with charter schools to help meet the needs of their districts and their increasingly diverse student populations,” Ryan said.

EdNews Data Analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.