College of Idaho graduate Peter Micah is in limbo.

After a nationally competitive hiring process, Micah was hired for his dream internship — a summer studying lithography at Micron’s Boise campus. The opportunity is his first, and only, chance to get real experience in his career field before starting a Ph.D. program at Boise State University in the fall.

But Micah’s internship is on hold — and has been for weeks — due to his visa status.

As an international student from South Sudan, Micah needs optional practical training (OPT) — a temporary extension of the F-1 student visa that allows international students to work in the United States for up to one year after graduation.

After completing a lengthy application process and dishing out over $400 to submit his application in May, Micah’s OPT approval is still pending, putting his employment and finances at risk.

And he isn’t the only one facing roadblocks.

Most international students at the C of I apply for OPT, according to McKay Cunningham, director of on-campus experiential learning at the Caldwell-based private college. The frustrating process — and the limitations that come with it — put international students at an “inherent disadvantage,” Cunningham says.

“They want to work, they need to make money, and they need to send some of that money to their families in their home countries,” he said. “They’re really frustrated with the suggestion that they can’t work like the domestic students can.”

A process fraught with limitations and frustrations

Most students apply for OPT during the final months of their senior year of college.

For students like Micah and fellow C of I graduate Thulasi Priya Ramesh, the process adds another measure of pressure to an already stressful period of life.

Micah graduated with three majors: chemistry, biomedical sciences and philosophy. He also earned minors in political economy and professional foundations, with biochemistry and pre-med specializations.

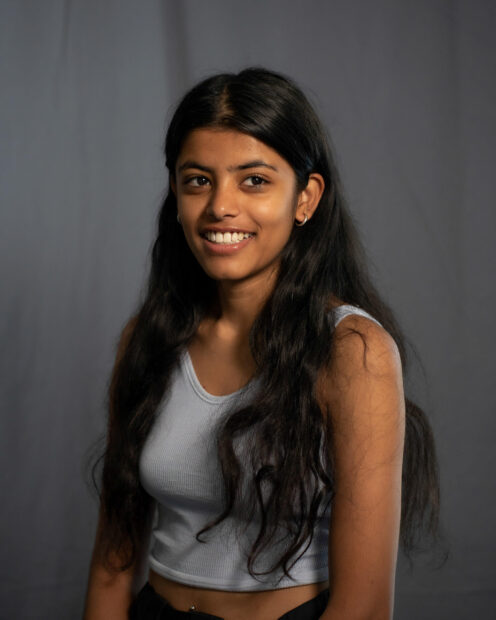

Ramesh, an international student from India, double-majored in international political economy and marketing and digital media. She worked on a 30-page thesis during her senior year, while also leading student trips for the college’s Outdoor Program and completing an internship in marketing and digital media.

On top of their busy schedules, the two spent hours completing their OPT applications.

Ramesh, who also hasn’t received her OPT, said the process was convoluted.

“It’s so confusing,” she said, outlining how the application requires thorough documentation. “It has its positives and negatives, but the process itself is complicated. It creates stress from freshman year that most people don’t even think about.”

For Ramesh, the job search wasn’t easy.

Employers hire for longevity; most workplaces want an employee who will stick around. But students on OPT get one year — sometimes three years for STEM majors — to work. Employers have to be willing to accept that, and support the intricacies that accompany OPT, when hiring.

Many choose not to.

On top of that, OPT-carriers must find a job that directly aligns with their major. An environmental science major can’t work in housing management, even if they’re the best candidate. And students facing an already limited job search are also on a strict timeline: from the time a student is approved for OPT, they have 90 days to find an eligible job and report their employment to the federal government, or they risk losing their visa for good.

“It’s very discouraging,” Ramesh said.

On the opposite end, students like Micah find suitable jobs before their OPT is approved — and they can’t do anything but wait. Not only does the delay limit their work experience, it puts a strain on their income.

“I’m praying I get it this week,” said Micah, who was supposed to receive his OPT by June 1 and begin working at Micron soon after. His start date was pushed once to June 12, and then again to June 20. If he doesn’t receive approval by his new start date, he’s considering volunteering his time with the company to get the experience he’s missing while he still can.

Both Micah and Ramesh expressed gratitude for OPT — without it, their options would be even more limited. But the process has taken its toll.

International students are an ‘asset’ to campuses and workplaces

Despite the barriers, international students are landing jobs in some of Idaho’s top companies.

The key is connections, said Ramesh, who will start a marketing job with the J.R. Simplot Company this summer, when she receives her OPT approval. The hiring team has recruited international students from the C of I in the past.

And the school’s administration agrees. Connections are important, said Cunningham, but international students also bring tremendous value and unique perspectives to Idaho workplaces.

“International students are absolutely critical to our campus,” said Cunningham. “They’ve landed a lot of really cool jobs. It’s a lot of work, a lot of frustration, but our students are really exceeding expectations all the time.”

“Our students are an incredible asset,” said Latonia Haney Keith, Vice President of High Impact Practices at C of I. “We’ve been talking to a lot of employers here in the Valley about the value of our international students, trying to get our corporations here to understand that there is value to OPT. Once our students are in the door, they do amazing things regardless of what the job is. And that just enriches our entire community.”

Christian Garcia, a former international student and student body president at the College of Idaho, said Micron supported him as he navigated a tricky immigration system. Garcia just finished his first year as an engagement coordinator for supplier diversity at Micron’s Boise campus, and will soon head home to Venezuela. His OPT expires in July.

“Once our students are in the door, they do amazing things regardless of what the job is. And that just enriches our entire community.” — Latonia Haney Keith, Vice President of High Impact Practices.

“Micron was one of the few companies that never really asked whether or not I had a way to stay in the U.S. long-term,” said Garcia. “I let them know that I only had a one-year work permit, and they told me that shouldn’t be a barrier, and that they would support me long-term. They helped with my immigration questions, and ensured that those conversations were always open and relevant.”

And Micron says the inclusion of OPT students in its workforce is part of its mission to expand diversity and inclusion efforts company-wide.

“We believe that when we work together to unleash inclusion in the workplace, we create breakthrough innovation,” said one Micron spokesperson. “That’s why we are committed to expanding semiconductor career opportunities to members of traditionally underrepresented communities.”

Micron and Simplot are just two of the companies that have fostered relationships with the C of I, and have supported dozens of international students on OPT. Others include the International Rescue Committee, Clearwater Analytics, D & B Supply and St. Luke’s Health System.

And for many international students, having that support from an employer makes a huge difference. They’re able to send money home to support their families, and build a life for themselves in Idaho — all while contributing to the local community and economy.

But that stability only lasts so long.

Most students only have one to three years before they need to figure out their next steps — many will either go to graduate school or leave the country after their OPT expires.

“It really is stressful,” said Ramesh. “I don’t really know what the next few years will look like.”