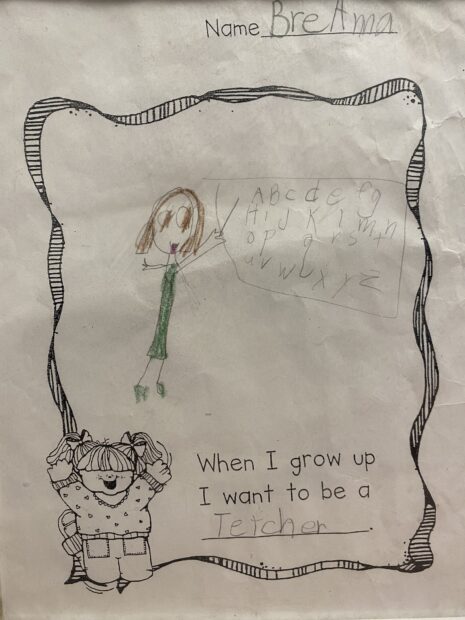

POCATELLO – Ever since kindergarten, BreAnna Leon knew she would become a teacher.

She saved a drawing to prove it — an adult version of herself saying: “When I grow up I want to be a tetcher [sic].”

Leon felt loved and safe in her childhood classrooms, and she intends to make sure future generations of Idaho students feel the same way.

But her idealism hasn’t shrouded the difficulties of teaching. Leon knows that teachers don’t often get the appreciation and recognition they deserve, and that some worry about how to make ends meet on their comparatively low salaries. She wants to become a teacher anyway.

“Kids need us,” she said. “I want to impact them regardless of the circumstances. If I’m not going to do it, who else will?”

In Idaho, districts have been scrambling to find enough teachers. With the school year well underway, dozens still have openings and many are experiencing atypically high turnover rates.

Emergency hires are becoming more frequent. College students are being pulled out of teacher preparation programs and thrust into schools before their training or degrees are finished. Applicants with a bachelor’s degree in any field (or even an associate’s degree) and a clean background check are being hired – even when they don’t yet hold a teaching credential.

Across the state, colleges of education have seen enrollment dips in teacher preparation programs, so they’re innovating new approaches to attracting students — like redesigning their programs or paying for paraprofessionals to become teachers. They’re also offering more support to early teachers, hoping they’ll stick around longer.

But college enrollment numbers aren’t low enough to account for Idaho’s teacher shortage. Instead, something is happening once teachers get into classrooms that’s making them leave. Simply put, enough people enter the profession but not enough stay.

Amid the shallow applicant pools and shortages, those who stand to suffer most are Idaho’s kids, whose teachers are more likely than ever to be undertrained, inexperienced or overwhelmed.

‘(Schools are) leaking teachers faster than we can replace them’

“At any given moment, there are thousands of people who are certified to teach in Idaho who choose not to,” said Sen. Carrie Semmelroth, D-Boise, who is also the director of strategic initiatives for Boise State University’s College of Education.

And that’s the problem.

Semmelroth said Idaho’s 10 teacher prep programs have produced a “steady supply” of about 1,200 teachers every year. And last school year, BSU’s number of graduates from the College of Education was higher than it’s been in the past seven years.

“When we talk about the teacher shortage, it’s not coming from the teacher prep side,” Semmelroth said. “There’s something happening once they enter the field. (Schools are) leaking teachers faster than we can replace them.”

The pandemic has been especially hard on teachers, said Sherry Dismuke, assistant dean of teacher education at BSU: “What was required of them and the pressure they felt and the changes they had to make were really difficult.”

On top of that, teachers are feeling the pressures of a more politically divided society.

“They are constantly wondering: ‘Am I presenting information in a way that is going to be acceptable to the clientele or the families that I teach?’ And that worries them,” Dismuke said.

And teachers bear a heavy responsibility to meet the needs of all students, ranging from those who are low-income, to English language learners, to those with special needs.

“Our teachers feel the burden because they have the heart for all the students in the classroom and they want to do all they can for them and sometimes those pressures just mount.” — Sherry Dismuke, assistant dean of teacher education at Boise State University

“Our teachers feel the burden because they have the heart for all the students in the classroom and they want to do all they can for them and sometimes those pressures just mount,” Dismuke said.

But it’s not just COVID-19 that’s brought teachers to the brink. Semmelroth said that even before the pandemic, the workforce was becoming younger and less experienced, and the attrition rate in the first five years was close to 50 percent.

“You can imagine how things have amplified since then,” she said.

Statistically, if teachers make it past the first five years, they’re more likely to stay in the profession.

That’s why Boise State is turning its attention to what it calls an induction program – in which it supports new teachers with mentorship, observations, coaching, goal-setting, and inquiry groups. Participants refine and revise their skills so they can become more effective, confident, and competent. New teachers get a stipend to participate in the induction program, and BSU is hoping to increase the voluntary involvement.

“We wish we could reach everyone and extend this to all teachers – that would be our dream,” Dismuke said.

Semmelroth said BSU’s induction program is especially important for students who are pulled out of their preparation program early to begin teaching; they often don’t have the “support, backing, knowledge, or skills” to feel successful. Too often, they become overwhelmed and leave the profession.

In the face of the teacher shortage, policymakers need to be careful “to not overreact to the teacher shortage and lower standards – to not have a knee-jerk reaction that leads to just anyone can be a teacher,” Dismuke said.

Instead, legislators should focus on keeping standards high, investing in induction programs, and increasing teacher pay – especially in outlying, rural districts, says Dismuke.

The next generation of teachers is shrinking

Taylor Raney, the director of teacher education for the University of Idaho’s College of Education, is similarly frustrated with the trend of districts hiring students before they’ve finished their teacher prep programs.

“More and more teachers are less prepared for the rigors of the role, and it’s only going to get worse if we keep cannibalizing the teacher prep programs,” Raney said. “We’re stepping over a dollar to pick up a nickel.”

For their part, districts only hire college students who haven’t yet finished their prep programs as a last resort – but that emergency scenario is happening more often.

Historically, there has been a “disconnect” between what students were learning in colleges of education and the realities they encountered when in a classroom. Raney said teacher prep programs have been working to remedy that.

Raney said today’s teachers are carrying heavier loads and facing more expectations than before without similar increases in pay and without “opportunities for influencing the system.”

“More and more teachers are less prepared for the rigors of the role, and it’s only going to get worse if we keep cannibalizing the teacher prep programs … We’re stepping over a dollar to pick up a nickel.” — Taylor Raney, director of teacher education, University of Idaho

But students are still choosing to enter the field because “they feel the calling.”

“I hate that because that’s what’s used to justify not paying them well, but the ones that are here, it’s just what they were meant to do and they are so excited about doing it,” Raney said.

Even so, the next generation of teachers is shrinking, Raney said.

So the U of I is stepping up its own teacher recruitment efforts. It recently hired someone specifically for that purpose. She’s been going to recruitment fairs, high schools, and using social media.

U of I, like other universities, has also been offering more pathways into the teaching profession. For example, they offer a master of arts in teacher education – targeting those who have a bachelor’s degree in another field and want to become teachers. The college has also been recruiting diverse students, and has a program tailored specifically to Indigenous educators.

Raney said the program has been “wildly successful” and attracted students from various states – though most return to their home states to teach.

Standards for incoming teachers need to be kept high

Lewis-Clark State College has also been innovating to attract education students. In the fall of 2019, it launched an online bachelor’s program in elementary education, which is appealing to paraprofessionals and place-bound students.

Mark Haynal, chair of LCSC’s teacher education division, said he would like to offer a similar program for secondary education degrees. Universities can increase the avenues to becoming a teacher, but there’s only so much they can do to keep them in the classroom, Haynal said.

He identified five main reasons for why teachers are leaving the profession:

- Poor pay, especially considering the level of education.

- Too much emphasis on standardized tests.

- Lack of respect from society and students.

- Lack of public support, especially when it comes to funding: “To leave the quality of education in a district to the whims of the voters is not a healthy thing to do,” Hyanal said.

- “Lousy” parents who shield their kids from the natural consequences of their choices.

“It is the overall sense of being unappreciated, which shows its face in teacher salaries, the workload, the buildings, and the cheapening of the profession itself,” Haynal said.

And legislators need to stop making it easier for unqualified individuals to become teachers.

“It’s a shortsighted emergency response, which seems to be all our government can come up with,” he said. “We’re not consistently attracting the best and the brightest to the profession, we’re just making it easier and easier to get in.”

Haynal’s got solutions in mind, too:

- “Hire good teachers, then support them and give them resources.”

- Study and learn from educational models in other countries.

- Get teachers that kids admire to promote the profession.

- Raise taxes to fund schools and eliminate bonds and levies.

- Create a culture of respect and a culture of learning.

Kids’ futures and livelihoods are at stake, Haynal said.

Education is a mirror to society

Kevin Talbert, an education associate professor at the College of Idaho, said schools are a product of their society.

Idahoans need to ask themselves: “If we look at the circumstances in our schools … are we satisfied with what that says about us as a people? About what we desire, where we place our priorities, and what we’re willing to fund?”

What he is seeing are teachers who are given less autonomy, trust, and respect to meet ever-increasing demands. Those conditions are extinguishing their hope and leaving them burned out and demoralized, he said.

Talbert wants to find ways to fan teachers’ hope and create conditions where they can “enact (what) they find so beautiful about the profession.”

But he knows that’s easier said than done.

“Schools are messy … They’re not a nice, neat, tidy thing to look at and there are not neat and tidy solutions.”

Incoming teachers: “It’s what I was meant to do.”

This academic year, every student at Idaho State University’s College of Education was offered a scholarship to entice enrollment. More than 35 paraprofessionals were awarded full scholarships to become teachers.

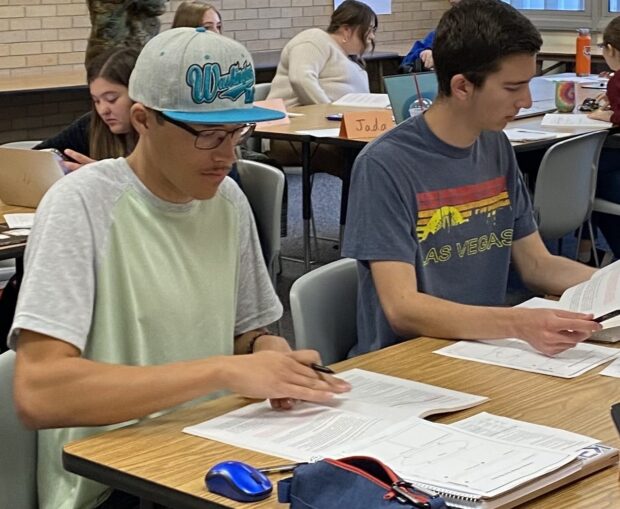

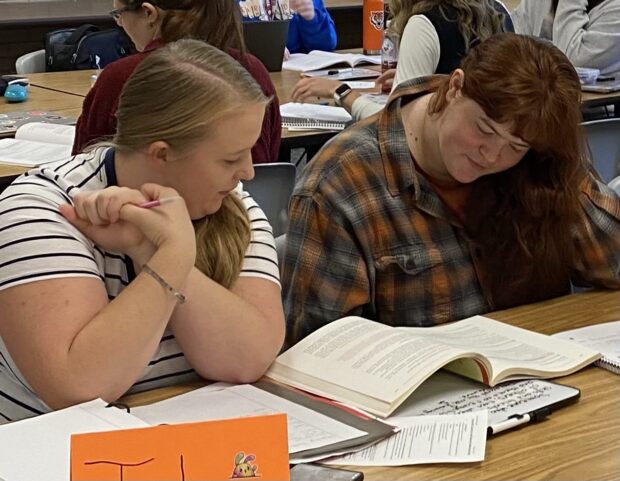

On a recent Monday morning, a class full of aspiring teachers took notes and participated in small group discussions. They were learning about how to craft meaningful learning objectives for their students.

One of the students, Morgan Hook, said she hopes to teach second, third, or fourth grade. Her classmate, Aubrie Samora, plans to teach fourth or fifth grade.

“I want to be an advocate for those students who don’t have one,” Samora said.

They’re excited about their career choice, but are also aware of teaching’s downsides. Samora said she will take mental health days when needed.

“My time is important,” she said. “Just because I’m a teacher doesn’t mean I shouldn’t take time for me.”

Hook and Samora worry about burnout and want to go into classrooms fully prepared. They won’t take teaching jobs until they complete their education.

Hook said the pitfalls of teaching are not enough to deter her from what she feels is her destined path.

“I love working with kids,” she said. “It’s what I was meant to do.”