This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

Get more details on Idaho results here.

Hopes for a post-COVID academic recovery were dashed Wednesday morning with the publication of new federal testing data for elementary and middle schoolers.

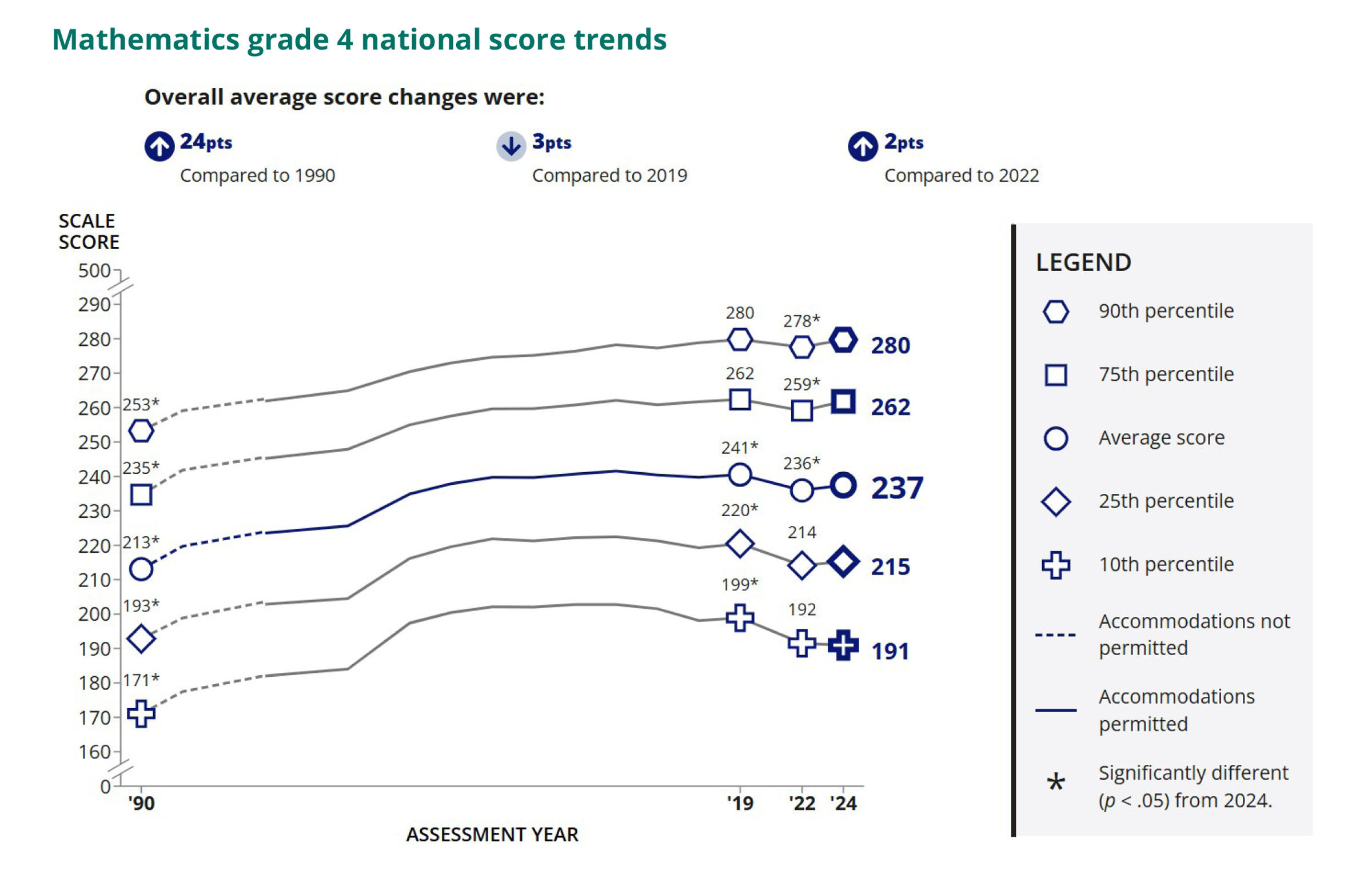

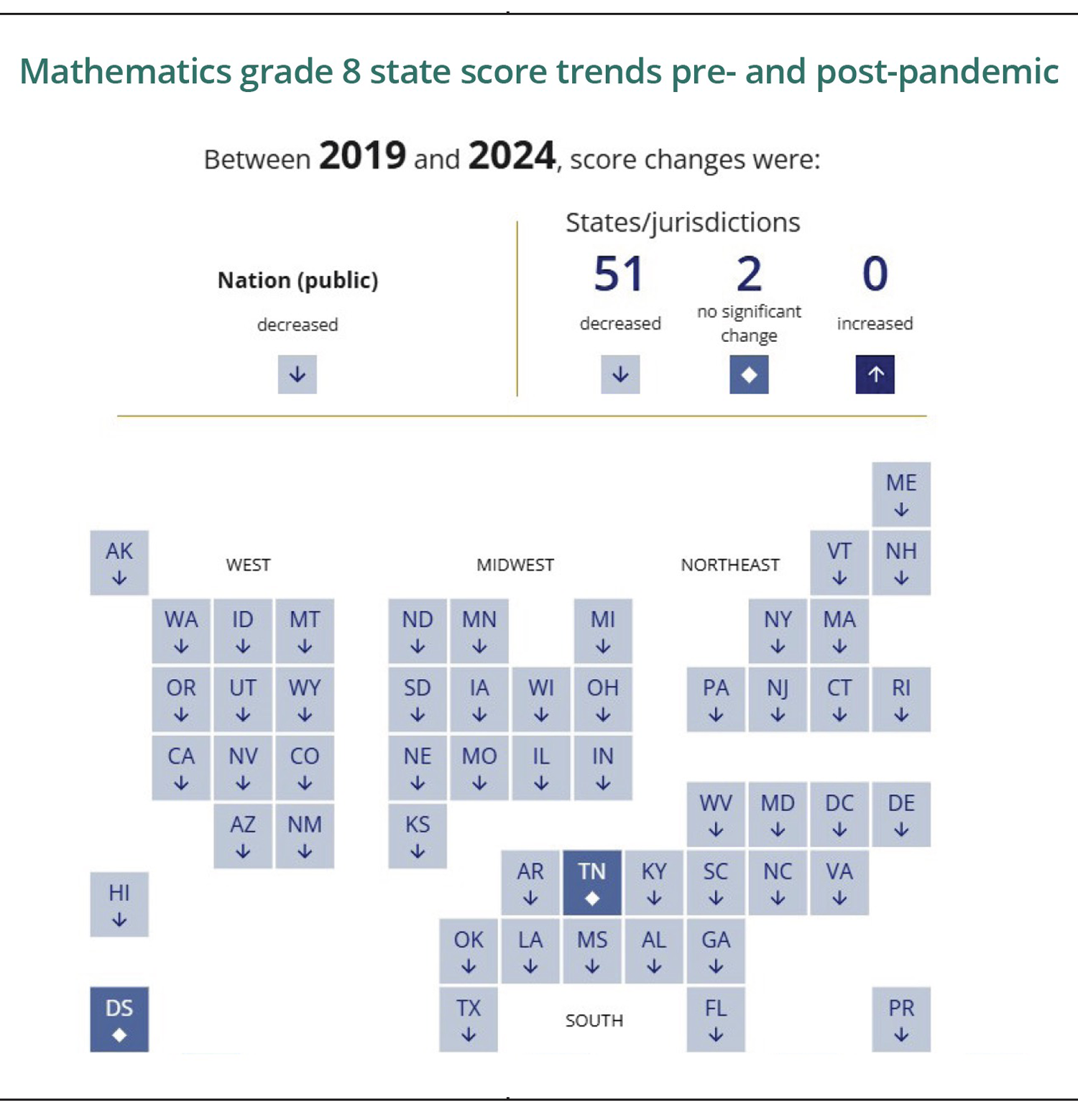

Newly released scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, often referred to as the Nation’s Report Card, show that both fourth and eighth graders have lost ground in reading — not just compared with the status quo of 2019, but also the most recent round of the exam, which was conducted during the heart of the pandemic. Math scores were flat for eighth graders and up slightly for fourth graders, but those gains were predominantly driven by the progress of high-performing students.

The alarming results are in keeping with those revealed by earlier iterations of NAEP and highlight decade-long trends of both stagnation in overall academic growth and growing disparities between top students and their struggling classmates.

Jane Swift was the Republican governor of Massachusetts from 2001 to 2003 and now serves on the National Assessments Governing Board, the nonpartisan entity that oversees NAEP. In an interview, she expressed frustration that the country is still “stuck where we were” two years ago.

“Everybody is tired of hearing about the pandemic,” Swift said. “This is not an issue that is driven solely by the pandemic. Looking at this data, it’s clear that we’re in enormous risk of losing an entire generation of learners unless we show some focus and leadership.”

The highest-achieving test takers continued to pull away, or at least hold steady, while lower-performing children lost yet more ground. In fourth-grade reading, only participants testing at the 90th percentile staved off a drop in scores; those at the 50th percentile fell by two points, and those at the 10th percentile experienced a four-point slip. In eighth-grade math, scores at the 90th percentile jumped by three points since 2022, while those at the 10th percentile fell by five points.

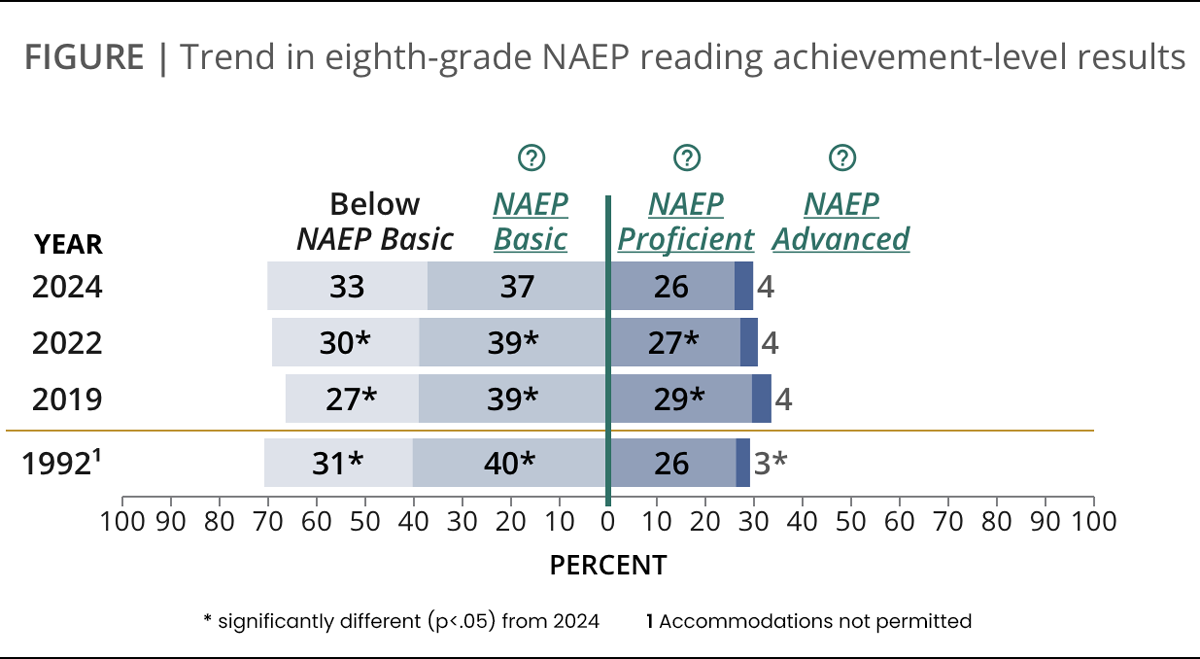

In all, about two-thirds of eighth graders exceeded NAEP’s “Basic” level of achievement in reading, fewer than did so in 1992. Thirty-three percent of students about to head into high school placed below the Basic threshold, the most in the history of the exam.

NCES

Julia Rafal-Baer, a NAGB member and education consultant who was previously the assistant commissioner of the New York State Education Department, said K–12 policymakers had to acknowledge the persistent failure to alter the trajectories of low-performing students.

“If we’re saying that a third of this year’s ninth graders are below NAEP Basic, we’re saying that one-third of these kids likely can’t tell us the main idea of a text,” Rafal-Baer said. “They can’t draw any explicit features from that text. What does that mean for these kids? What’s the plan to re-engage them and improve their outcomes?”

Some hopeful signs in math

Even with the abundance of bad news, some positive signs indicated the beginnings of a turnaround in math learning.

Fourth graders climbed upwards by two points in the subject over the last two years, after dropping by five points between 2019 and 2022. While falling somewhat short of a major stride — again, higher-scoring students enjoyed significant gains, while those at the bottom of the distribution did not — it marks the first sign of post-pandemic progress on NAEP.

Bob Hughes, director of American K–12 education programs at the Gates Foundation, said that while it was critical to track year-to-year fluctuations in math scores, national leaders in government and philanthropy needed to focus more on the broader development of better tools and strategies to deliver math instruction. Compared with the decade-long coalescence of educators around the science of reading, which has taken hold in dozens of states around the country, no similar consensus exists for math, he argued.

Further, he added, a host of technological applications and tutoring models has continuously evolved since the emergence of COVID. While the best classroom use of such innovations is still to be discovered, Hughes described himself as bullish on their long-term prospects.

“I don’t think the technology is positioned now to be a magic bullet in solving some of the challenges we see on NAEP,” Hughes said. “But there are some promising developments that, over time, should help us accelerate achievement amongst even students that are the farthest from standard.”

Among results for individual states and school districts, often closely watched for exceptions to national or regional trends, comparatively few distinctions were in evidence. Fifteen states, mostly clustered in the Northeast and South, enjoyed a significant bounce in fourth-grade math compared with 2022 (Nebraska was the sole state in which scores declined over the last two years); still, only Alabama elementary schoolers are now farther along in the subject than similarly aged students in 2019.

Another exception was Louisiana, the only state in which fourth-grade reading scores were higher than in 2019. Notably, the state’s scores in fourth-grade math were also higher than in 2019, though not by a statistically significant amount. Local losses in eighth-grade math and reading were among the smallest of any state.

John White, who served as Louisiana’s superintendent of schools from 2012 to 2020, said the state’s progress was due to a long-running emphasis on the improvement of curricular materials and strong accountability.

“There have been changes to rules and programs over time,” he said, “but the essence of the plan remains constant: select evidence-backed curricula, build teachers’ skill every day on the practices needed for those curricula, and be transparent about the results schools achieve.”

White added that the “jarring” results for the nation as a whole could not all be attributed to the hangover of COVID learning loss, and that education leaders have to arrive at a better understanding of how to improve them.

“We have to look deep within the test results themselves, and across a broad range of factors inside and outside of schools, to come to a stronger hypothesis than we have today,” he concluded. “That should be a national priority, and if national leaders don’t lead it, prominent state and city leaders should.”