At the end of past school years, Laura Pearson could close her eyes, tick through her English curriculum in her head, and assure herself she’d taught her students what they needed to know.

She’s not so sure that’s the case following the 2020-21 school year.

As Idaho Falls bounced between in-person and hybrid learning this year, Pearson’s typical calendar went out the window. She didn’t follow her usual timeline or teach topics the way she had in the past. Now she closes her eyes and worries: “Did I teach this? Did I teach that well enough? Are they going to be okay?”

“I feel completely stressed because I feel like I let down my students,” Pearson told EdNews last week.

Her end of year stress punctuates what many teachers say has been the most stressful year of their careers.

First, a global pandemic forced educators to pivot to new learning models, reach students remotely, and in some cases teach virtual and live classes at the same time. Then add politics. Teachers and unions weighed in on tense debates around mask mandates and in-person school days. And when the Idaho Legislature convened this spring, they accused teachers of trying to indoctrinate Idaho kids with liberal ideologies.

Teachers are burned out, Idaho Education Association president Layne McInelly said, an issue that could prolong Idaho’s challenges in recruiting and retaining teachers and paraprofessionals.

“I’ve never had so many educators reaching out to me for advice, and sharing their concerns and looking for another profession, honestly,” McInelly said. “It’s at an all-time low. We need to work as a community and as a state to help educators, so they can continue to help our students in public schools.”

Over 40 percent of teachers and classified staff say they were more frustrated and burned out at the start of 2021 than ever before, according to an IEA poll.

That’s not just an Idaho challenge.

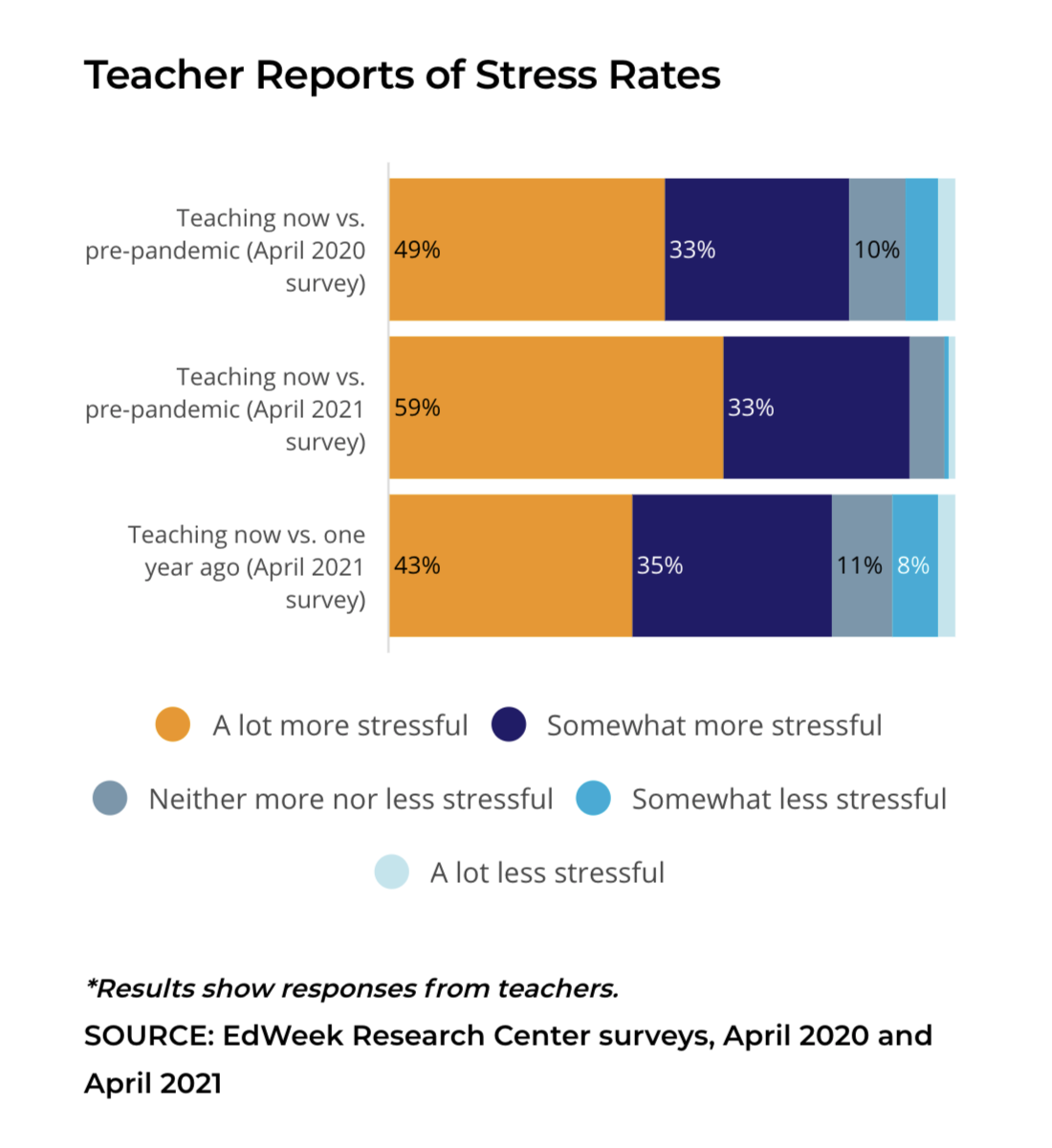

An April survey by the Education Week Research Center found that teachers are not only more stressed than before the pandemic — they’re also more stressed than in April of 2020, when the pandemic first struck.

That tracks for Pearson.

When Idaho schools shut down because of COVID-19 last spring, and teachers scrambled to move classes online, “we realized it wasn’t going to be perfect,” she said. For a time, teachers felt respected by parents and the public who praised them for trying to connect with students despite pandemic barriers.

That sentiment has since evaporated. As McInelly sees it, teachers have become the scapegoats for pandemic and political frustrations.

“We went from being heroes to villains in months,” said Melissa Stroupe, an elementary teacher in the Lewiston School District. “It’s been disheartening to attend board meetings and hear parents speak about how we need to take the bullet, how we’re to blame for suicides, that this is what we signed up for — without recognizing that we are fighting to keep all of these kids in our schools, in the safest possible environment where they can learn.”

Teachers also feel disrespected by legislators, who accused them this year of trying to “indoctrinate” youth with a liberal agenda, and “social justice ideology.” Pearson said it’s impossible to avoid discussions around social justice in her high school English courses, where she teaches books like To Kill a Mockingbird.

“I’ve spent a lot of money and a lot of time getting my masters to learn how to teach things with best practice,” Pearson said. “Having the legislature tell me how I can and cannot teach things in the classroom is just very frustrating.”

Add the burden of catching students’ up from a global pandemic, navigating scheduling instability and trying to stay safe from a raging virus, and Pearson says she’s never been more stressed or exhausted. Stroupe, a union leader, gets calls on a daily basis from teachers looking for advice or dealing with breakdowns.

“Teachers mental health has been tested beyond its breaking point. Teachers have been left broken and helpless and I feel like we’re lost,” Stroupe said.

McInelly says improving teacher morale is a responsibility shared by educators, community members and all levels of government. He advocates for investing in lower class sizes, adding more paraprofessionals, counselors, school nurses and psychologists to help care for kids, and prioritizing educators’ mental health.

Pearson says teachers shoulder a responsibility, too.

“We have a martyr system, that the more they shovel onto teachers the more they’ll do because it’s for the kids,” she said. “Until teachers stand up and say, ‘no,’ they’re going to have to keep repeating the cycle.”