School district leaders are priming for a year that could be more financially daunting than the last as they continue to reel from the impacts of losing a pandemic-era boost.

Last school year, a one-time influx of funding alleviated budgetary woes. Now, district leaders are confronting financial blows that can no longer be softened or delayed.

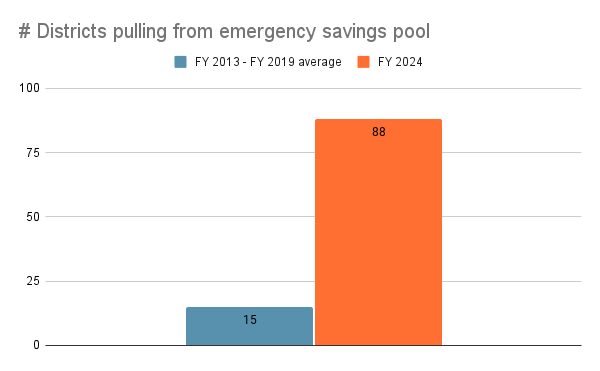

To complicate matters, an emergency savings pool meant to safeguard districts didn’t work as intended. That’s because nearly 90 Idaho school districts hit a redline last school year, as opposed to about 15 in a typical year.

Simply put, because of the unprecedented need, the funding pool’s financial assistance was minimized or even negated.

The savings pool debacle provides a window into the tricky financial waters district leaders continue to navigate amid post-pandemic efforts to return to normal.

Some districts are reducing staff, closing schools, and/or increasing student fees. The hurt eventually trickles down to students, who might find themselves in larger classes, paying more to play sports, or being shuffled to a new school.

A number of factors have sparked the shortfalls, including declining birth rates, increased housing costs, students switching to charter schools or home schooling, and bond and levy failures. While which factors come into play is highly dependent on the district, one factor impacts most districts — a change in how the state doles out dollars.

Since the pandemic, the amount each district gets has depended on student enrollment numbers, as opposed to attendance. Enrollment-based funding generally meant increased —and more predictable — funding.

Last school year, state officials reverted to the pre-pandemic status quo, and attendance once again became tied to funding. Because of that, some school districts faced suddenly losing millions of dollars.

A few saving graces, with mixed success

State superintendent Debbie Critchfield successfully secured $145 million from the Legislature last spring to shore up the financial gap created in the switch back to attendance–based funding.

Districts got another $11.4 million this summer after the full school year’s data was calculated and the fiscal gap was found to be $156.4 million, according to Gideon Tolman, the Idaho Department of Education’s chief financial officer. The $145 million was an estimate intended to be adjusted later if needed.

Getting those dollars secured was not a sure thing, and in the meantime, school leaders had to run their districts and manage their finances without counting on them.

District leaders were also hoping to get some relief from what’s basically a pool of savings that they chip into every year. The pool offers them a financial lifeline if attendance suddenly nosedives — budget hits are cushioned until the next school year, giving leaders time to plan.

Here’s how the emergency savings pool (called the protection clause) works:

- Each year, districts chip in a chunk of their budget (support units).

- In return, they get security. If their attendance rate drops 3% or more from the prior school year, that would have a notable impact on their budget. So, in that case, they get to pull some support units — or state budgetary dollars — from the pool.

- Basically, it offers them a one-year extension before they feel the brunt of the financial pain from declining student attendance.

Breaking down jargon: What’s a support unit?

A support unit is a measure used to calculate how much funding a district gets from the state (and attendance is now a part of that calculation). It essentially represents the cost to operate a classroom. Simply put, the more support units, the more money a district gets. Last school year, an average support unit equated to about $141,660 in state funding, according to Julie Oberle, the state’s director of public school finance. But the specific amount varies by district.

But this year, the savings pool did not work as intended, Tolman said. That’s because there “was such a big hit to all districts.” About 77% of districts, or 88 of 115, qualified to pull from the pool.

That’s extraordinary compared to typical years — when maybe 15 districts would qualify.

To consider that jump in another way, let’s look at the number of support units pulled from the pool: 647, as compared to a typical 11.

And because so many districts had to draw from the pool, that meant all the districts had to chip in more as well.

Typically, districts contribute a relatively small amount of their budget to the pool each year — or about 0.08% of their support units, to be exact. Last school year, that figure ballooned to 4.43%.

What all this means varies from district to district. Some may have benefited somewhat from the pool. For others, it may have been a draw between what they gained and paid in. And some districts, who didn’t qualify for protection, lost as they had to pay in much more than usual.

Tolman said last school year was an “anomaly.” Barring any unforeseen major events — like a pandemic — the pool should stabilize for this coming school year.

“We’re looking forward to it going back to normal,” he said.

FYI: Charter schools don’t have a similar emergency pool, but could create one if interested, according to Oberle.

By the numbers: A look at districts with big drops

Nine of the state’s largest 10 districts qualified to pull from the emergency pool last school year — all but Oneida School District, which mostly comprised online students (so attendance dips are less likely).

For those in the education trenches, it’s shocking to see so many large districts hit the redline — especially the state’s largest, West Ada.

“No one ever dreamed that they would (hit the redline) because they’ve been growing, growing, growing,” said Julie Oberle, the state’s director of public finance. West Ada has basically contributed to the fund to be “a good team player,” not expecting they’d need to pull from it.

But expectations were upended last school year.

Here’s a look at the impact a reversion to attendance-based funding had on large districts.

Ten largest districts

| District | Change in support units, 2022-23 to 2023-24 |

| West Ada | -140.37 |

| Boise | -84.94 |

| Bonneville | -49.53 |

| Nampa | -46.56 |

| Pocatello | -44.71 |

| Coeur d’Alene | -35.34 |

| Idaho Falls | -37.42 |

| Vallivue | -38.21 |

| Twin Falls | -31.81 |

| Oneida County* (not protected) | -17.55 |

Double-digit changes

Here’s a look at some other districts statewide where the decrease in support units hit double digits. These districts all qualified to pull from the savings pool, except for Madison School District.

| District | Change in support units, 2022-23 to 2023-24 |

| Post Falls | -25.05 |

| Jefferson County | -24.89 |

| Kuna | -22.5 |

| Cassia County | -19.97 |

| Caldwell | -19.41 |

| Madison (not protected) | -19.37 |

| Lewiston | -19.03 |

| Lakeland | -17.93 |

| Blackfoot | -16.48 |

| Middleton | -16.17 |

For a complete list of districts statewide and their change in support units, go here.

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.