Budget shortfalls and declining enrollment have driven a spate of recent school closures in Idaho — a trend that’s disproportionately impacting vulnerable student populations.

It seems to be an unintended consequence, as trustees are not closing schools based on a student body’s demographics, academic performance, income levels, or other such factors. Instead, they are taking into account a building’s location, condition, and enrollment numbers.

Even so, struggling students are most likely to be displaced. It’s unclear how closures will impact their education, as national and local experts have differing opinions.

As more school leaders grapple with difficult financial decisions, they may be looking to this first wave for answers.

In the past six months, at least seven school districts have announced or considered school closures. That’s just 6% of all traditional school districts statewide, but it’s an about-face from overcrowding issues that have plagued school districts like Idaho Falls and Middleton.

These communities are on the frontlines of budgetary woes that are increasingly impacting schools in Idaho — and nationwide — as leaders confront a fiscal cliff driven in part by expiring COVID dollars.

In Idaho, schools are closing in West Bonner School District (Priest River Junior High School); Caldwell School District (Lincoln Elementary School); Coeur d’Alene School District (Borah Elementary School); and Nampa School District (West Middle School; Centennial Elementary School; Greenhurst Elementary School; Snake River Elementary School); Leaders in Boise are considering closing Owyhee Elementary School, and Marsh Valley is considering closures. Trustees in Mountain View just avoided closing two schools when voters approved an unlikely levy, after four previous consecutive failures.

The impacted school districts are diverse — ranging from the affluent tourist haven of Coeur d’Alene, to urban Boise, to rural districts in North and Southeast Idaho.

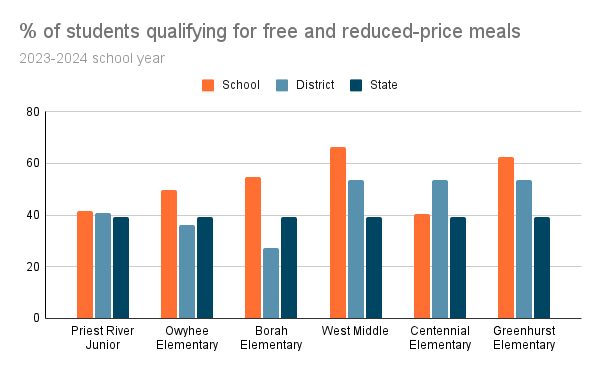

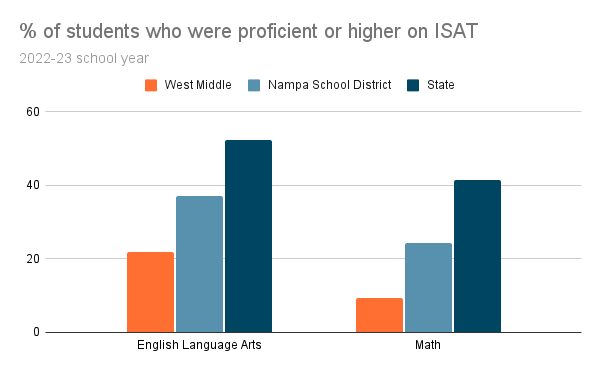

But most of the schools slated for closure are home to vulnerable student groups, who are more likely to underperform their district and state peers on standardized tests; belong to minority groups; and/or be from low-income families, according to an EdNews data analysis.

For example, last spring, students at elementary schools that are or might be closing were not reading as well as statewide peers, and were less likely to read as well as district peers.

The schools in question were also more likely to have to a higher percentage of students qualifying for free and reduced-price meals than district and state peers.

Stakeholders, in Idaho and nationwide, have mixed opinions on what the increase in school closures mean for students and educational equity. On one hand, it could allow students to learn in better environments. On the other hand, it could be disruptive for students to move to a different building with new classmates, teachers, and leaders.

Some parents have pushed back; Boise parents opposed the potential closure of Owyhee Elementary School, which school leaders proposed converting to an early childhood learning center. That proposal is now on ice.

Rural communities have been vocal, too — especially because closures can mean children commuting to different towns, rather than different neighborhoods. In Priest River, West Bonner trustees recently decided to close a junior high, rather than one or more elementary schools, partly due to patron concerns.

National experts and leaders weigh in on the debate: what do school closures mean for equity?

Georgetown University education experts predict that, on a national scale, “high-poverty communities will see sharper impacts to their school budgets in part because of how federal relief dollars were distributed. Students in those communities were also more likely to fall behind academically after the pandemic. “The question now is whether leaders will take action to ensure that our most vulnerable students don’t once again feel the brunt of the effects,” wrote researchers Marguerite Roza and Katherine Silberstein.

In Denver, Colo., school trustees are already facing hard decisions amid budget setbacks. They recently approved a new policy aimed at protecting underperforming students from displacement: A superintendent may not use test scores as the sole reason for a school closure.

Debate over the policy, and whether test scores should be considered at all, was “the most heated” part of the discussion, Chalkbeat’s Melanie Asmar reported. One board member said standardized tests are “based in racism,” and shouldn’t be considered at all.

Michael J. Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, an education reform think tank, sees it differently.

In an interview with EdNews, he said school leaders should intentionally close low-performing schools, then move the students to higher-performing schools, be it a traditional or charter school. He defines higher-performing schools as those with the greatest academic progress from year to year — which doesn’t necessarily equate with the highest scores in the district or state.

“Rather than promise that school closures won’t disproportionately affect low-income communities or communities of color, promise that all affected students will have access to higher-performing schools,” he wrote in a February blog post.

The perfect storm behind budgetary woes in Idaho

Idaho traditional school leaders faced with planned or potential school closures point to a perfect storm of contributing factors. In addition to expiring COVID relief funds, they’re contending with:

- A shift from enrollment-based funding to attendance-based funding.

- In some cases, failed ballot measures.

- Overwhelming school maintenance needs (even after recent legislation siphoned $1.5 billion in new facilities funding, just nine of the state’s 116 school districts could afford to build a new elementary school).

- An influx of older residents who don’t have school-aged children, as in Nampa.

- Students opting out of traditional schools in favor of charters, online schools or home schooling.

At the same time, Idaho’s fertility rate has steadily dropped since 2014, with the exception of a slight uptick in 2019.

And last school year, student enrollment was down statewide for the first time since the height of the pandemic, though charters and online schools saw some significant growth.

Some of these driving factors — like declining birth rates — have been apparent for years, statewide and nationally.

But an influx of pandemic dollars “helped districts kick the can down the road,” Petrilli said. Now that those funds are drying up, districts are having to face the tough choices they postponed.

“This year especially, boards will be in the hot seat as districts grapple with cuts that affect those in their community,” Marguerita Roza and Laura Anderson, directors at Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab, wrote in a recent op-ed for The 74 Million.

Closing schools can get students in better learning environments

In Nampa, where four schools are closing, Superintendent Gregg Russell said school leaders primarily considered the shape the buildings were in and their enrollment numbers when deciding which to shutter or repurpose.

“It did not have anything to do with academic performance,” he said. “It was really looking at the whole picture of our schools that were half-filled.”

In fact, he said, considering achievement data as part of closure decisions had never crossed his mind: “I don’t think closing a school for purely academics is really a great idea.”

Instead, school leaders were thinking about logistics and expenses. For example, only about 500 students attended West Middle School last school year — a smaller population than at some elementary schools. That meant low class sizes of 12 to 14, as opposed to 28 to 30 at other middle schools. Small class sizes are “lovely” but costly, Russell said.

In 2022-23, West Middle students underperformed district and state peers by large margins on the Idaho Standards Achievement Test.

An analysis by Georgetown researchers digs into why it’s cost-prohibitive to run schools with low attendance — largely because of overhead and staffing: “Closing three schools can save the costs of three principals, three librarians, three nurses, and so on, and even some teaching positions where students can fill empty seats elsewhere in the district,” wrote Marguerite Roza and Aashish Dhammani.

Nampa’s closures will save money, but Russell said it will also get students into better buildings.

For example, at-risk students at Gateways, an alternative school, have been learning at an elementary school that’s nearly 70 years old. “It’s not a great fit for them. The rooms and hallways are tiny,” Russell said.

Now they’re moving into the former Snake River Elementary, which was built in 1995 and is “in much better condition,” Russell said.

Districts like Nampa could be leading the way for others facing financial straits. For those in similar situations, Russell had three pieces of advice: “You have to be a good steward of the finances; you have to be responsive to the community; and you also need to benefit the students. Somehow, you have to weigh all three of those to make the most important decision, and that really will (vary) community by community and district by district.”

In Marsh Valley, leaders wade into early school closure talks

While closing schools might be financially efficient, communities don’t want to lose their hubs.

Located in rural Southeast Idaho, Marsh Valley School District operates seven schools across five small communities: Lava Hot Springs, Arimo, Inkom, Downey, and McCammon.

“People in each of these little towns have a very distinct identity,” Superintendent Gary Tucker said in a June 5 interview. “Each of the towns in this valley have a different personality and they don’t necessarily see things the same way.”

Because of that, residents in each want to keep their local school. But “we can’t afford to run it the way it is,” Tucker said.

That’s partly because of low enrollment. The district lost about 55 students from 2022-23 to 2023-24, about a 4% change.

This fall, Tucker anticipates fewer than 20 students in Downey Elementary’s combined fifth- and sixth-grade class, and just 40 students across seven grades at Lava Elementary. In some cases, there are as few as eight students in a class.

“It’s nice having small class sizes, but it’s really hard to staff it appropriately,” Tucker said.

School leaders are looking into turning Lava Elementary into a charter school in the fall of 2025, and are considering consolidating the three remaining elementary schools. But conversations are preliminary and “we are certainly open to other ideas on balancing the budget,” Tucker said.

“If there’s a better option, let’s go with a better option. Right now, that’s just one of the things that’s on the table as we try to figure out what we’re going to do with fewer kids in the district.”

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.