This fall, three new charter schools are opening in partnership with their local districts, reversing a trend of rivalry.

Charter schools and traditional districts have historically competed over academic outcomes, enrollment and public dollars. That was problematic, because at first only local districts could sponsor — or “authorize,” in education parlance — charters.

When traditional district leaders weren’t exactly champing at the bit to help out seeming competitors, the state created the Idaho Public Charter School Commission to serve as an oversight body if districts were unwilling.

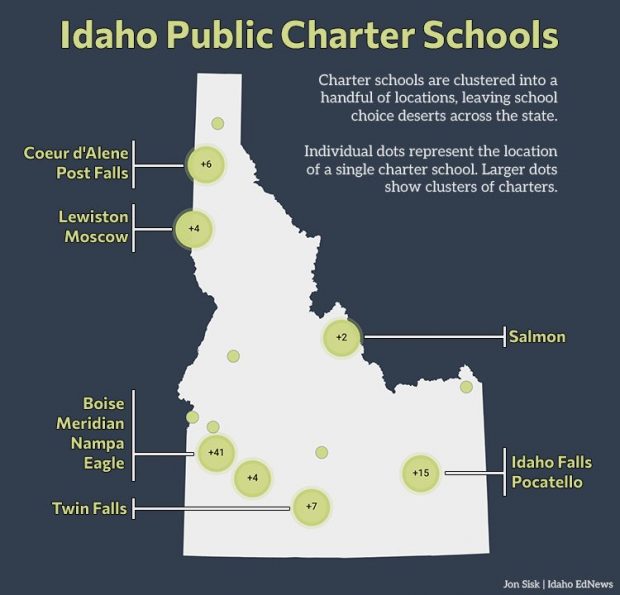

Today, most of Idaho’s charters — 58 of 76 — operate under the commission’s auspices. Only 14 school districts, or 12%, authorize a local charter.

It’s an unlikely time for local partnerships to grow. For one, charters are growing while traditional district enrollment is shrinking. Faced with declining student numbers and an incoming fiscal cliff, some districts have had to shutter schools.

But a few districts are taking charter schools under their wings this fall — some to fill a niche gap for students.

West Ada School District will authorize Pathways in Education, opening this fall. The school, which has a sister site in Nampa, provides hybrid, nontraditional learning opportunities for students.

“It’s just a really unique system that, to be honest with you, we don’t have,” Derek Bub, West Ada’s superintendent, said in a news release.

Bonneville School District is authorizing Elevate East, a move that could help more students graduate but will impact the district’s budget and staffing. And Oneida School District is transitioning its online school to a charter to gain financial flexibility, Superintendent Jon Abrams said, but is keeping ties as the school’s authorizer.

The partnerships are something charter advocates have long pushed for, in part because they would reduce the workload on the understaffed commission.

Terry Ryan, the CEO of Bluum, a nonprofit that supports Idaho charter schools, said the ultimate goal is to use charters “to improve student learning and opportunities.”

“I think we have superintendents in Idaho who truly care first and foremost about their students and families and if partnering with a charter creates better opportunities for students why not partner?” he wrote in an email to EdNews.

But district charter partnerships have to overcome a fraught history.

Charters and districts: A rocky relationship from the start

Because school funding depends in part on enrollment numbers, losing students meant losing dollars. As a result, some traditional district leaders saw charter schools as threats.

Competition over enrollment is heightened today, amid declining birth rates, a shift to homeschooling, rising housing costs and other factors. Some traditional districts have recently had to close schools, partly because of declining student numbers.

At the same time, charter schools are showing the most growth — which could be in part to new schools that are constantly popping up.

Charter school authorizing: A timeline

1998: The Legislature passes a law allowing for charters, and the first schools open their doors. At this time, only traditional districts can authorize charters.

2004: New legislation allows for the creation of the Idaho Public Charter School Commission, which fuels criticism around the state that it will take away local control.

2013: New legislation allows Idaho colleges and universities to start authorizing charters.

2024: The Legislature passes a wide-ranging overhaul of charter school law, which in part allows charters to cut down on red tape in startup and renewal.

Another area of contention is opposing educational approaches: Charter schools have often been initiated “in spite of the local district,” as Kimberly School District Superintendent Luke Schroeder put it. Parents, educators, or other stakeholders who are fed up with the local schools start their own.

So when districts don’t want to support a local charter, the commission steps in.

See which 14 districts in Idaho authorize charters.

But recently, the commission has been marked by dysfunction amid a seeming identity crisis over whether it should be a gatekeeper or a cheerleader — sparking a departure of leaders who were ousted or stepped down amid ideological disagreements.

There have also been questions over how best to hold charter schools accountable. Some in the charter community have pushed for less emphasis on academic outcomes, and more on enrollment numbers. Amid the chaos and history of contention, some districts see solutions in charter schools: a way to save a remote school, a way to fill niche student needs or a way to find new funding sources.

New charters can have financial and staffing impacts on their local districts

Deciding to authorize a charter can have costly impacts, Bonneville School District superintendent Scott Woolstenhulme said. But in some cases, it’s worth it.

Bonneville recently agreed to authorize Elevate East, which opens this fall. The career technical charter fills a gap for the district by serving vulnerable students in sixth- through 12th-grade; Bonneville’s alternative school primarily serves grades 11 and 12.

“We want … to ensure every kid graduates high school,” Woolstenhulme said. “We’re not catching some of those kids early enough in the process, or providing enough support to them, but Elevate could be able to do that.”

The decision has its downsides: Bonneville expects to lose as many as 150 students to Elevate — and up to $1.2 million in accompanying state funding.

“It is going to be a hit to our budget,” Woolstenhulme said. Some supplemental state dollars “and our fund balance are what’s going to carry us through this coming year.”

Staffing has been impacted as well, as some Bonneville teachers have taken jobs at Elevate.

“Losing kids, and losing good teachers, it definitely has hurt the morale, especially at our alternative high school,” Woolstenhulme said.

But Elevate East would have arrived in the community with or without district authorization, Woolstenhulme said, so it made sense to form a partnership with them “rather than what has typically been a fairly competitive relationship.” This way, the charter and district could share some resources — like split the cost of a school resource officer.

“There’s a good opportunity to … build a more collaborative relationship than we’ve had in the past with other charter schools in the area,” he said.

‘We’re an invited guest:’ Alternative charter fills a gap for West Ada

The state’s largest district, West Ada, is also authorizing a new charter this school year, partly because of its unique offerings for a niche group of students.

Pathways in Education (PIE), aims to provide a nontraditional learning opportunity for students, who run the gamut from those looking to graduate high school and start college early to those balancing full-time work or parenthood while trying to earn a diploma.

PIE is unusual in other ways: Classes are hybrid, with two in-person days required each week, and the rest online. It serves ninth- through 12th-graders, and students up to age 21. Its “schools” are rented storefronts in strip malls. And minimal overhead costs means school leaders can offer paid national and international field trips to qualifying students.

Susan Lux, senior director of schools for PIE, said Nampa and West Ada have treated the schools like one of their own. Recently, for example, PIE leaders got to tour West Ada’s existing alternative schools and meet their leaders.

“We’re an invited guest, so the treatment is different, the process is different,” Lux said. “We’re not viewed as a competing school … We are part of their offerings.”

How authorizing a charter works

The Idaho Department of Education monitors charter schools and traditional districts. If a charter is authorized by a district, it is monitored as if it were one of the district’s schools.

- The district monitors the charter’s academic progress, operational systems and finances and ensures the school is in compliance and meeting goals.

- The charter and authorizer work together to determine the goals the charter must meet. But it’s up to the charter how it achieves them.

- The district completes reviews periodically and determines whether it should renew the charter, renew it with conditions for improvements or reject renewal. Here’s a look at a recent performance review for an example.

- Districts can charge charter schools for their oversight and services.

PIE is one of three charters West Ada oversees.

“What we always look at with our charter school applications is, does it offer opportunities for our students that we currently either don’t have the capacity to offer or don’t currently offer? PIE really is that opportunity,” Bub said in a recent Bluum press release.

In another new partnership popping up this fall, a charter school became a financial solution.

Troubled East Idaho district turns its online school into a charter, seeking financial flexibility

Oneida School District’s troubled online school became a charter on July 1.

The Idaho Home Learning Academy has seen exponential growth since its 2016 inception. Now, IHLA’s approximately 7,000 students far outnumber the district’s in-person population of about 1,000.

Abrams said he urged the board to transition the school to a charter mostly to gain more flexibility with state funds. Charters, for example, can use staffing dollars in more creative ways, rather than exactly as the state prescribes.

Admittedly, the loss of those 7,000 students will create a financial hardship, Abrams said.

“We’re having to tighten our belts,” he said.

The district initially started IHLA to generate funds, which have gone toward facilities upgrades and other expenses, Abrams said. “Those opportunities are now gone.”

The Oneida district has recently been under scrutiny for systemic violations of federal special education law at IHLA. The Idaho Department of Education will oversee IHLA’s special education programs for the next three to five years because of systemic issues. That oversight will continue even though IHLA has become a charter, IDE spokesperson Maggie Reynolds said.

Oneida has also been in the news for poor academic achievement results. Its K-3 students showed the worst reading regression in the state last school year, for example. And it is suing the state over wording in a facilities law that could cost the district $7.7 million.

“We’ve had some bumps and bruises, and … we’ve got a lot of work yet to do,” Abrams said.

Oneida is maintaining ties with IHLA as its authorizer, and Abrams said the two programs will benefit each other: “We see it as a win-win,” he said.

Another East Idaho district, Marsh Valley, is also considering converting an existing school into a charter. It would be a way to save Lava Elementary School, which could face closure amid declining enrollment, Superintendent Gary Tucker told EdNews last month.

While some districts are moving to partner with charters, one is stepping away

For 25 years, since its founding, Pocatello Community Charter School has been authorized by the Pocatello/Chubbuck School District.

But for years, the district has been pushing PCCS to switch and become authorized under the commission — a move PCCS Director Michael Mendive has “dragged his feet on.” While the commission provides oversight, Mendive said, it doesn’t offer “a mutually beneficial relationship.”

“When you’re a charter school, you’re on an island,” he said. “We are a tiny little (charter) so having a thinking partner where we are supporting one another sounds nice.”

Mendive had hoped for a third option: that an Idaho university might step up to authorize PCCS. But none agreed to do so. That’s been the case statewide since universities were permitted to become authorizers in 2013 — something charter advocates have called out and pushed for repeatedly over the years.

When charters first came about, they were intended to be a way to “serve as learning laboratories with hope that successes could potentially be applied throughout the larger public education system,” according to a report prepared by Bluum.

While it never quite worked out that way, Mendive has wished for that kind of teamwork. A university partner could use the charter as workforce training for teachers, counselors, speech pathologists and others, for example. A local district could learn some of the school’s best practices, like its focus on character development and project-based learning.

And PCCS could stand to learn plenty from either, he said.

But that chapter is closing as PCCS seeks commission authorization, at the district’s behest.

Mendive emphasized that the district “has been really great and kind to us” but just is not interested in a partnership.

Courtney Fisher, Pocatello/Chubbuck school district’s communications director, did not respond to a request for comment about the authorization switch.

‘We just can’t be territorial about education’

Ryan recently told EdNews that “growing school districts will see the advantage of partnering with charter schools to help meet the needs of their districts and their increasingly diverse student populations.”

He points to partnerships like the one between Kimberly School District and RISE Charter.

One crucial aspect of their story: RISE began as a brainchild of district leaders.

That was four years ago, and now it’s an integral part of the district’s offerings, said Schroeder, the Kimberly superintendent. The district provides most of RISE’s overhead, like the building, transportation and support services.

In turn, RISE opens doors to new funding avenues, like federal charter grants. And area students get more educational options.

“You have to look at education for your entire community, not just your district,” Schroeder said. “It’s human nature to be competitive, but we’ve got to put our egos aside and see what’s best for kids … At the end of the day, we just can’t be territorial about education.”

Further reading: Idaho’s charter school movement squashed fears, filled needs, and created alternatives

Disclosure: Bluum and Idaho Education News are both funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation. The foundation does not take part in EdNews’ editorial decisions or content.