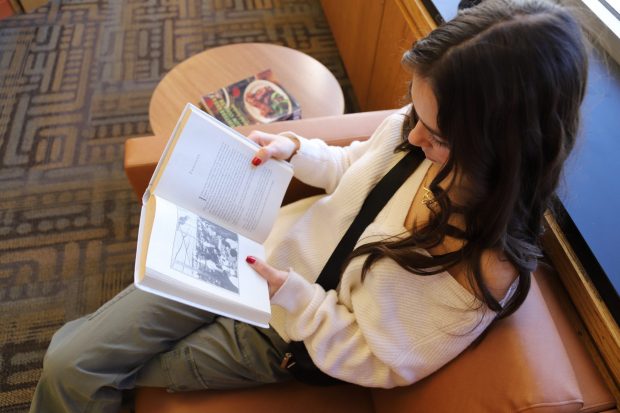

When Olivia Lanzara needs solace, she heads to her school library to lose herself in a book.

On one such occasion, she checked out a fantasy series by Sarah J. Maas. The books’ “powerful female main character” who perseveres against the odds inspired and uplifted the Rocky Mountain High junior.

Last month, two of those books were among 10 quietly pulled from West Ada school library shelves after a private meeting among administrators.

“It made me feel really helpless,” Lanzara said.

She’s not alone.

West Ada librarians and students say they’re frustrated and disheartened after district leaders removed the books without considering their perspectives, under an unusual policy that gives the superintendent, or an otherwise designated district administrator, wide latitude to remove books.

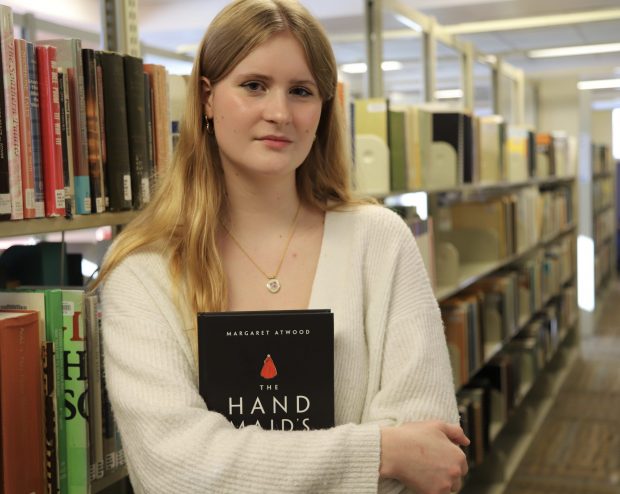

“It leaves a very bad taste in my mouth,” Annabelle Jenkins, a senior at Idaho Fine Arts Academy, said. “We need to feel heard, we need to feel involved.”

West Ada leaders held another closed-door meeting last week to consider removing more books from a list of 44 that are under fire based on ratings created by a group of “concerned parents” in Brevard County, Florida.

Niki Scheppers, the district’s spokesperson, said no decisions were made.

Stakeholders in West Ada schools say the book removal policy goes too far, and fear that not just books — but libraries and free-thinking — are under attack. District leaders say the policy is an effort to proactively get inappropriate materials off of shelves, and to do so as quickly as possible. They also say they’re listening to concerns and reviewing procedures.

Statewide, school leaders are paying attention; West Ada’s policies often set a precedent.

Pushback against the book removals in Idaho’s largest school district comes as legislators have introduced multiple bills that would impose harsh consequences — including closure and fines — for libraries that allow minors to access books deemed “objectionable” or “harmful.”

“More than just books are under attack, libraries themselves are under attack,” Lanzara said.

Monday, hundreds gathered at the Capitol to weigh in on House Bill 384, which would require librarians to relocate books that patrons deem objectionable to an adults-only section or face a civil lawsuit. Most testified against the bill, but it still advanced out of committee.

West Ada’s unusual book removal policy places power in superintendent’s hands to expedite removals

West Ada’s book removal policy includes an unusual clause that allows for a “district administrative review,” which essentially gives Superintendent Derek Bub (or another designee) the ultimate say over which books are kept or removed.

He can decide to review a book, facilitate a meeting about it, then pull it from every library in the district. While the policy permits stakeholders to voice concerns with Bub’s choices, he is not required to respond or take any action.

“You could say it’s a dead end,” said Jonathan Schoenfelder, a former library aide at Renaissance High who felt comfortable speaking on the record because he resigned last month.

That’s in contrast to book removal policies at other large districts, including Boise, Bonneville, and Nampa. In those districts:

- The policies are designed for parents or patrons to initiate book challenges, as opposed to the superintendent.

- A book review committee must have a majority vote to remove a text (so multiple people make the decision).

- Appeals processes are established.

- Final decisions after appeals rest with trustees (and become public).

When a West Ada parent or patron complains about a book, the district’s policy is similar to that of its peers. But the administrative review clause sidesteps most of those procedures in order to expedite the removal of books with content deemed illicit or inappropriate, Scheppers said. Plus, the policy means district leaders don’t have to wait for patrons to request a book’s removal, and can proactively start the process themselves.

Schoenfelder, who left West Ada for a position as a university librarian in Pennsylvania, said the process doesn’t represent “very good librarianship.”

The district did invite a few librarians to participate in its private December meeting, where the decision to pull 10 books was made. They all declined.

Here’s how the process, called administrative review, works:

— Initiate the review: The superintendent can call for a review of books at any time. He will then schedule a meeting with “the most appropriate” district employee.

— Meeting and decision: A decision will be made at the meeting, which can be applied districtwide “at the discretion of the Superintendent or designee.” Removed books are placed on the “Declined list.”

— Input: Concerns about the decision should be made in writing to the superintendent and three other district administrators. At that point, “the Superintendent will make a final decision regarding the text/learning resources.”

Librarians feel their professional opinions are not respected or taken into consideration at such meetings, Schoenfelder said, so they have stopped participating. A second West Ada librarian, who asked to remain anonymous due to fears of repercussions, confirmed that.

“It can feel disappointing and demoralizing when our voices aren’t well-heard, or when policies are created without much input from secondary school librarians,” said Schoenfelder.

“Despite (librarians’) current decision not to participate, we remain open to continued dialogue and collaboration,” Scheppers wrote in a statement. “We value the expertise of librarians, and their input is essential to our collective success.”

In December, Schoenfelder wrote to Bub and administrators to voice his concerns about the removals.

“This is bad pedagogy and speaks very poorly to the direction the West Ada School District is headed,” he wrote, urging Bub to restore the pulled titles — especially Allen Ginsberg’s “Collected Poems,” a book Schoenfelder read and connected with in high school.

He called the administrative review process “poorly conceived and badly bungled” and said it should be “remade through a collaborative process with actual school librarian input.”

The recent removals set a dangerous precedent, Schoenfelder told EdNews.

“We’re way past the slippery slope,” he said. “We’re now in a full-blown process where (administrators) feel empowered to just cut out swaths of books without talking to the school board about it. And so we’ve slipped down the slope, you might say.”

Scheppers said the district is “actively reviewing our current procedures and seeking ways to enhance transparency in the book removal process. We acknowledge that open dialogue is crucial in fostering a supportive and inclusive learning environment.”

West Ada student: “Libraries are not only resources, they are refuges.”

Lanzara and Jenkins, who attend different West Ada schools and do not know each other, have been pleading with adults to hear them out.

“I think we’re only listening to one perspective right now, and that’s what’s causing a lot of this harm,” Lanzara said.

Jenkins said the review process “shut the student involvement out of that conversation.” She believes kids should have a voice, even if adults make the final decision.

Scheppers said district leaders are taking student feedback seriously: “We understand the importance of transparency in decisions that impact our students’ educational experience, especially in matters as significant as the removal of books from our district’s libraries.”

The teens said it’s not just books that need protecting, but libraries as a whole.

Lanzara said she keeps hearing adults say that kids no longer read or care about libraries: “I want adults to know that kids are actively reading … The library is a safe place for a lot of students. If you have anxiety, you can go there and de-stress.”

“Libraries for me have always represented safe spaces for creativity and exploration,” said Jenkins, who aspires to become a librarian. “Libraries are not only resources, they are refuges, especially for children.”

During her freshman year, which fell during the height of Covid, Jenkins was lonely and scared — so she went to the library.

“In a school they’re absolutely vital to students’ mental health,” she said. “I cannot imagine my childhood without a library or without books, or without knowing that I had the possibility to explore different worlds.”

Scheppers said West Ada’s “commitment to preserving the traditional library experience remains strong.”