In our fastest growing communities in counties like Ada, Kootenai, Canyon and Twin Falls our public schools (district and charter alike) are adding students faster than we can build classrooms to house them. This growth has been acknowledged and debated by the Funding Construction of Public Schools working group co-chaired by Sen. Dave Lent and Rep. Jason Monks.

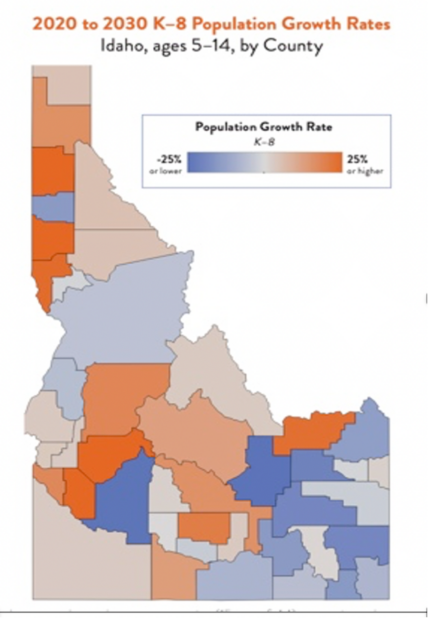

Over the past decade, our state’s overall K-12 enrollment has grown by about 55,000 students, almost 20 percent (10,422 students) of which has been in the state’s public charter schools. With all this growth in student enrollment, public schools in Idaho—both traditional school districts and charter schools—have struggled to keep up with the need for new and expanded school facilities. As demonstrated in the map below this growth is expected to continue through at least 2030. It’s estimated we will need to build 98 new elementary schools for 39,400 elementary school students alone by 2030.

But, as the map also shows, not all Idaho counties are going to be adding people and not all of our schools are going to be adding students. Some rural districts are seeing declining enrollments as their overall population declines, while some wealthier school districts are losing students because their housing costs are driving out young families with children. The contrast couldn’t be starker between the new building spree in the Boise School District where student population is flat but property taxes have never been higher, to rural districts where many superintendent rate upwards of 60% of their buildings fair or poor.

As an Idaho Statesman headline read recently, “Idaho school bond failures show the gap between haves and have-nots, need for reform.” Our poorest rural school districts and public charter schools are the biggest have-nots—they can’t even dream of passing (in the sake of smaller poor rural districts) or even seeking (in the case of charters) public bonds or levies for facility costs.

This “facility gap” is especially pronounced when comparing needier rural and public charter schools to property-rich school districts like Boise, which passed a $172.5 million bond in 2017, or Blaine County, which passed a $25 million plant facilities levy in August. Nor can charter schools or needier rural district dream big; like the Idaho Falls School District seeking a $250 million bond issue, Kuna School District possibly seeking a $300 million for facility construction or West Ada looking at more than $334 million for school facilities.

Despite the funding inequities Idaho’s public charter schools are an important part of the solution to overcrowded classrooms. This fact goes largely unrecognized and unappreciated by study groups and the traditional education stakeholder groups. Over the last seven years Idaho’s public charter school sector has built 20+ school facilities for some 8,000 public school students at more than $150 million in construction costs. Some of these are brand new buildings, but others are facilities located in old department stores or other buildings that were going unused.

They have been stellar deals for our taxpayers and parents as no local tax dollars have gone into these charter facilities; and as these schools overall deliver results for families and their children. They also offer some of Idaho’s most innovative learning opportunities from rigorous American Classical Education, to STEM to International Baccalaureate to Career Tech.

But, as costs of land, materials and labor continue to accelerate Idaho’s public charter schools need the state to do more if they are to continue helping to meet the needs of a growing student population. To illuminate the scale of the facility financing challenges circa December 2022, and most importantly to offer up some solutions, my organization Bluum partnered with the Foundation for Excellence in Education (ExcelinEd) to generate the new policy brief, Building for Success in Idaho. A key takeaway from the brief is that because of facility financing inequities, “an average-sized charter school in Idaho must operate on average with nine fewer teachers, diverting funding intended for student instruction to pay for facilities.”

The ExcelinEd research team, led by Matthew Joseph, built on the facility financing work and methodology they created for Indiana, Ohio and Tennessee to produce the policy brief and an interactive tool that demonstrates how much the facility needs of charter schools in Idaho are currently being met and how they can be better met by the choices and decisions at the statehouse.

In sum, facility financing for school districts and for public charter schools is complex and varies greatly across our state’s geography and public school type.

There are a variety of choices and pathways that can be taken by state lawmakers to improve facility financing fairness for our students. Some of these policy solutions, like charter facility credit enhancement, have already been developed while others, such as a revolving loan fund, continue to be debated. Solutions that work for public charter schools may or may not work for traditional district schools.

For example, public charter schools have grown accustomed to using their operational dollars to meet facility costs. This is all they have known. District schools have not had to do this. Providing charter schools with new facility financing tools like a revolving loan fund, might fairly need to be matched by providing our neediest rural districts with direct state grant support to meet the costs of facility improvements or upgrades that their local taxpayers can’t meet on their own.

Let’s all be mindful that our schools’ facility financing needs vary widely across our state. Thus, our solutions should also be flexible and not constrained by old ways of doing things. Our children deserve nothing less.