West Ada, West Ada, West Ada.

On top-ten lists from the state’s most prominent academic achievement measures, the school district was everywhere.

Its schools repeatedly outshone their peers on the Idaho Standards Achievement Test and the Idaho Reading Indicator. And the district far outpaced other large districts when it came to scores on both exams.

So what sets the district apart?

West Ada leaders will tell you the difference is mindset: Teachers and leaders who believe they have more to learn. From top to bottom, staff members keep asking: How can we do better?

To find the answers, they’re sitting in on classes, personalizing and perfecting professional development, crunching student achievement numbers, and defining what it means to be a great teacher — in their own terms.

“It takes everybody at every level being willing to be open minded and willing to learn and improve their craft. Because if we’re growing as adults then the students will grow too.” — Shana Hawkins, West Ada’s director of accountability and success

As Shana Hawkins, the district’s director of accountability and success, said: “It takes everybody at every level being willing to be open minded and willing to learn and improve their craft. Because if we’re growing as adults then the students will grow, too.”

In a district where student success makes headlines, here’s what leaders are doing differently.

Facts and figures: A portrait of West Ada by the numbers

First, it’s helpful to have some context about West Ada — what it is and isn’t, according to the data.

West Ada is:

- The state’s largest district by far, with about 38,000 students and 58 schools. (The runner-up is Boise with about 22,000 students)

- Because of that is has more resources — more state funding, more taxpayers to shoulder the costs of levies and bonds, and more staff members.

- Home to the highest-paid superintendent in the state. Superintendent Derek Bub currently makes about $215,000 — more than any other superintendent, including Debbie Critchfield (who makes about $129,000).

- Home to a higher percentage of students from middle-to-high income families than the state average. West Ada’s percentage of students from low income families is 23%, as compared to the state average of 40%.

- Otherwise comprised of a student population that is comparable to state averages. (See chart below).

| West Ada demographics | State average demographics | |

| Enrollment by race/ethnicity* | White (77.5%); Hispanic or Latino (12.2%); Multiracial (4.9%); Asian (2.5%); Black/African American (2%) | White (73.8%); Hispanic or Latino (19.2%); Multiracial (3.4%); Black/African American (1.2%); Asian (1.1%); Native American or Alaskdan Native (1%) |

| Students learning English | 4% | 6% |

| Students with disabilities | 11% | 12% |

| Students in foster care | <1% | <1% |

| Students who are homeless | 1% | 2% |

| Students from migrant families | <1% | 1% |

| Students from military families | <1% | 1% |

*including only groups that comprise 1% or more of the population

Source: idahoschools.org

West Ada is not:

- The biggest spender. It spends about $6,600 per students, as compared to the statewide average of $9,800 spent per students.

- The district with the highest-paid teachers. Its teachers make about $57K — just above the state average of $55K. Neighboring Boise pays its teachers an average of $67K.

- The district with the most experienced teachers. About 72% of West Ada teachers have six or more years of experience, as compared to 65% statewide, and about 81% at Boise School District.

- The district with the highest teacher retention rates. West Ada’s retention rate is about 84%, as compared to the state average of 87.9% and Boise’s rate of 85%.

Marcus Myers, the district’s chief academic officer, and Bub both acknowledged that West Ada’s size gives it some advantages — like a low tax rate.

The district’s large staff is another plus. For example, Bub’s cabinet includes unique positions that don’t exist in every district, such as these:

But Myers said the most important game-changers are not staff or resources, but belief systems and district culture: “You have to create a culture of instructional changes based on what kids do and don’t know, and then you have to create a tool to measure that along the way.”

West Ada’s tool: frequent checks for learning.

How teachers turn data into a learning opportunity

Throughout the year, West Ada students take practice (or formative) tests to create data on their learning progress. Those practice check-ins are not required by the state, but West Ada still requires them district-wide.

“We don’t rely on just … the data that tells us where we landed the plane at the end of the trip,” Myers said. “We make sure that we’re following that progress along the way.”

After each round of practice tests, teachers have a scheduled PD day to analyze the data — because otherwise, the numbers would be meaningless, Kelly Davies, director of assessment and achievement, said.

“It’s in the action that you see results, and action has to come from the analysis of data,” Davies said.

And data is just part of the picture; teachers’ relationships with students fill in the rest of the story.

“The numbers on the page only say so much; there’s the story of the student as well,” Davies said. “The teacher has that with them, and that will never be something that can be on a spreadsheet.”

After evaluating the full story and multiple data points, teachers can then decide next steps based on student needs.

Admittedly, it’s a time-consuming process and it requires buy-in.

Part of that is changing the culture around tests, Myers said, and getting teachers and students to see them as tools to help learning, instead of tasks done to comply with laws.

“Every possible check we can have along the way — if it leads to better results — everybody wants that win, right?” Myers said.

District-level administrators also analyze student achievement data monthly. If multiple data points identify a low-performing school or class, they send in a team of what are called “consultants,” or instructional coaches, to help support the teacher and get students back on track.

West Ada teachers are constantly learning from data — and from each other.

Learning tailored to teachers: Professional development that works (or is adjusted when it doesn’t)

In West Ada, professional development for teachers stands out for what it’s NOT:

- It’s not a “sit-and-get” lecture style information session

- It doesn’t feature national (and usually pricey) speakers

- They are not one-size-fits-all, giant PD sessions that the entire district gets, regardless of content area or grade level

Instead, they are interactive sessions designed and tailored for specific small groups, and they’re often led by in-house teachers and staff.

For example, teachers at Prospect Elementary participated in a scavenger hunt at one staff training — they were sent to look at their peers’ classrooms, paying attention to how they wrote and displayed what are called learning intentions and success criteria.

Breaking down jargon: Learning intentions and success criteria

The terms, well-known to teachers, basically mean the learning goal (what students should know or be able to do by the end of a lesson or unit) and how progress toward that goal can be measured. The idea behind them is that students will be able to self-assess and understand where they are in their learning journey.

“That was fantastic, and it was very well-received,” Gwenda Venecia, the school’s principal, said. “Now we have more ideas for how to write these more effectively and impact students with them.”

That’s the kind of professional development that’s worthwhile for teachers.

“We want it to be very applicable to what they’re doing,” Marcus Myers, the district’s chief academic officer, said.

“It really comes down to this idea that what a teacher does in the classroom really matters for the longevity of students and we need to consistently work to improve our craft, just like in any business,” Bub said. “We always need to strive to be better.”

And Patricia Vandenberg, a math coordinator in the curriculum and instruction department, said it’s important that the training isn’t based on the newest teaching fad, but on practices that have been around for a while, been proven effective, and are well-researched. Letting teachers slowly adapt to new techniques is important too.

“In education, we are guilty of having too many initiatives, like every year is a new initiative and a new focus,” she said. “It comes down to going slow to go fast.”

Basically, the district strives to run its training the same way they would ask a teacher to run a classroom — with great instructional strategies, clear goals, and engaged learners, Myers said.

And every time teachers have training, they also get at least a few hours to “digest what they’re learning” and think about how they can incorporate it into their teaching.

And teachers need to know they aren’t being asked to overhaul their entire way of doing things — just incorporate little bits and pieces at a time.

“When we’re talking about changing habits, it takes small steps and being consistent,” Vandenberg said.

Myers said staff meetings are shifting away from traditional informational rundowns, and toward staff members sharing instructional strategies. That way, teachers can get little bite-size PD more often than the dedicated four days a year.

Admittedly, some professional development sessions are “flops,” Bub said.

“But we need to hear that as well, so we don’t repeat that. We make sure that when teachers walk out of our professional development, they’re 1% better than they were the day before.”

The district’s leaders are also expected to keep learning — in part by getting into classrooms more often, without letting paperwork or meetings get in the way.

Back to class: Principals in the classroom, learning alongside students

Last spring, the district initiated what it calls “instructional rounds.”

Here’s how it works:

- One principal hosts a handful of other administrators or leaders at his/her school. Together, they visit a teacher’s classroom and watch and observe the instruction, then discuss and reflect on what they saw.

- It’s a process that takes up to three hours.

- Principals and school leaders participate in this two to three times a year.

This is different than a typical observation, which usually involves one administrator sitting in on a class as part of a formal teacher evaluation, for a few reasons:

-

- Multiple administrators from various schools are present.

- The teacher volunteers to host the administrators and knows when they’ll be coming.

- The administrators are not focusing on what the teacher could do better, but on what they the leaders could improve based on what they saw.

It seems simple, but the change is having an impact already.

Leaders are telling Vandenberg that it’s the best professional development they’ve ever had.

And it’s not just principals — the district’s highest-level administrators, including its chief academic officer and superintendent — participate, too.

“I don’t want school leaders that don’t know what it’s like to be in the classroom.” — Derek Bub, West Ada Superintendent

“I don’t want school leaders that don’t know what it’s like to be in the classroom,” said Bub, who said he visits classrooms at least three days a week.

Vandenberg got the idea for the practice from a book: “I was really inspired. I’ve never read a book so fast.”

She originally spearheaded the program, piloted last spring, to help improve math instruction. But then participants were quickly asking to expand it to all content areas — which the district is doing this year.

The sit-ins help leaders better understand what good instruction looks like in each subject (because best practices for teaching senior-level math are likely a bit different than they are for teaching freshman-level English) and in turn, they’re able to provide better feedback to teachers.

“Teachers are just in the thick of it,” Vandenberg said. “They’re in the trenches battling it out, and they need leaders that can tell them one small thing they can work on, give them a different perspective, and help them refine their craft.”

And every six weeks, administrators get another training opportunity — they spend a half day at the district headquarters, participating in professional development designed just for them.

West Ada didn’t have to reinvent the wheel, but they did anyway: Defining what great teaching look like, in their own terms

Many schools use the Charlotte Danielson framework to determine what great teaching looks like. The framework includes pre-written checklists and goals that teachers can use to better their craft, and that principals can use to evaluate them.

West Ada leaders didn’t have to reinvent that wheel — but they did anyway, generating their own descriptions and benchmarks for effective instruction. Plus, building the checklist became a valuable learning opportunity in and of itself.

“There’s power in learning by doing, so when we build it together, there’s a level of ownership,” Myers said.

The checklists are based on established research, but are tailored to West Ada’s district and goals. Here’s what one looks like.

So while the Charlotte Danielson framework, for example, focuses on what the teacher is doing, West Ada’s checklist also focuses on what students are doing.

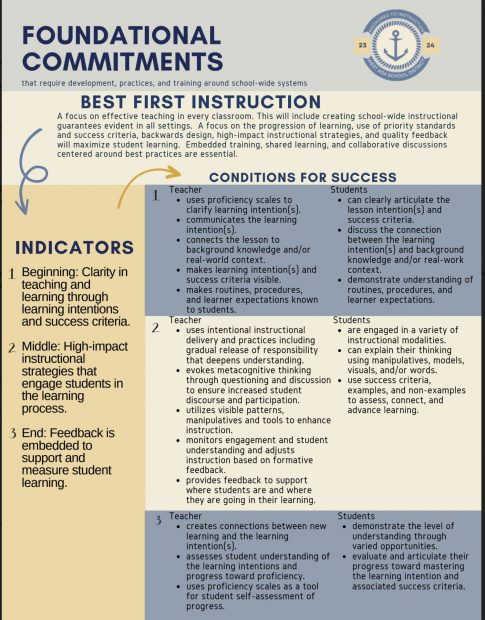

District leaders have also built their own best practice guidelines called “foundational commitments,” which guide instructional efforts (see below). This year’s focus is on best first instruction.

Now teachers, principals, and administrators can use a shared language and be on the same page.

After all, students’ futures are at stake.

“We have an obligation, an imperative, a responsibility to make sure that our kids are successful after high school,” Bub said. “That’s what makes our graduation so exciting — we collectively believe that our students have those opportunities when they walk across that stage.”

Data Analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.